[Author’s Note: This is the second half of one of the rare monthly columns where I covered more than a single film. The first half featured Ben Hecht’s Specter of the Rose, which is referenced in the opening line below.]

“We’re not athletes, we’re baseball players.” –Tom Selleck, in Mr. Baseball

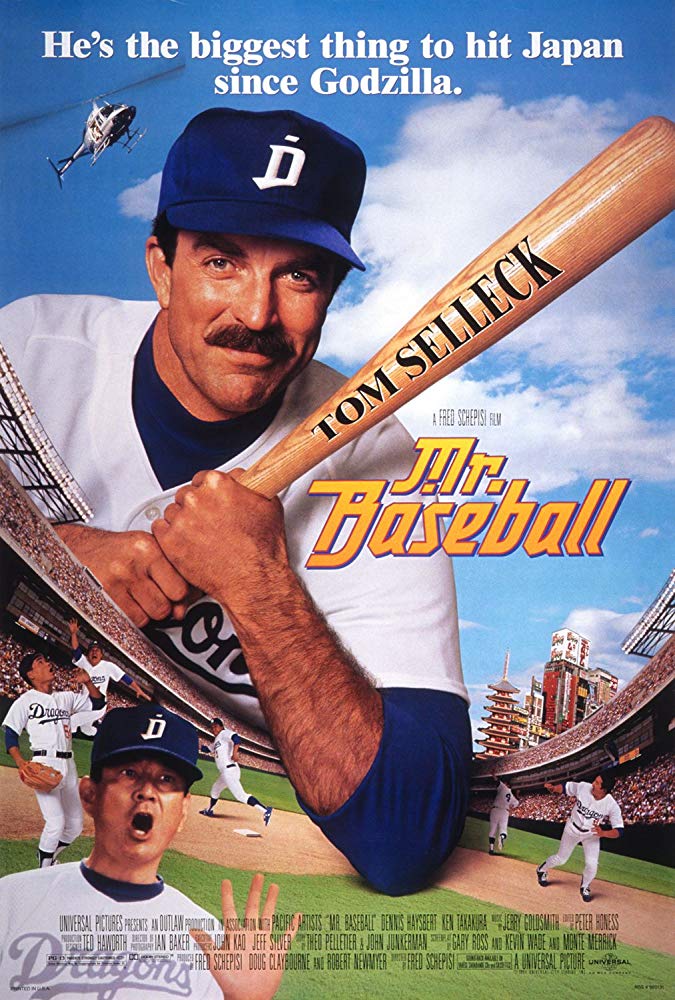

Where Hecht and company aimed high and hit low, the Japanese culture shock movie I’m going to write about aims at the middle and hits right on. The film is Mr. Baseball, starring Tom Selleck, Ken Takakura Ava Takanashi, and Dennis Haysbert. As the choice of actor to play on-the-skids major leaguer Jack Elliot, the kind of American “barbarian” that the Japanese simultaneously admire and loathe, Selleck is perfect. He’s got an ingratiating, irresistible charm mixed with a permanently juvenile mind-set that only a sledgehammer can dent. Batting in the low 200s with the Yankees, and despite his owning two World Series rings, Jack is farmed out to the Nagoya Dragons. For him that’s a fate worse than Canada (“I’m not gonna pay those taxes”) or Cleveland.

The fact that Japanese baseball clubs that hire American players like Jack know exactly the kind of problems they’re going to have doesn’t make the whole exchange process any smoother. At first, it might look like straightforward masochism on the part of the Japanese. What’s really going on involves a little one-upmanship and an astute exploitation of “barbarian” skill, juicy marketing opportunities, and sheer entertainment value. As long as both parties are willing to adapt to some of the demands of the other’s game plan, everyone ultimately benefits. Mr. Baseball is about Elliot, his Japanese coach, and his Japanese girlfriend all learning the kinds of compromises that mutually enrich cultures. The characters learn a lot about one another, and the viewer learns a good deal about Japanese besoboru. In the movie, the director used documentary footage of real crowds at real games, and highlighted some of the dos & don’ts of daily life in Japan.

I must admit I avoided this movie when it first came out for fear that it would be just another case of Hollywood’s shallow stereotyping, or, even worse, of the kind of America-First attitude demonstrated in Black Rain and Rising Sun. I changed my mind about watching it when Scott Cobbe, a high school teacher from the nearby city of Creston, whose two-year sojourn in Japan I’d followed through his fine columns in the Creston Advance, told me that Mr. Baseball hit pretty close to the mark. I wholeheartedly agree. I’ve visited Japan on several occasions, and was lucky enough to be treated to tickets to a Hiroshima Carp home game. Baseball fans who’d like to follow up on the subtleties of the Japanese game should track down a copy of Robert Whiting’s excellent book You Gotta Have Wa. For anyone else thinking of traveling to Japan, here are a few of the questions Jack Elliot might have liked to know the answers to before he learned them the hard way:

What don’t you do with a Japanese business card?

What do you do before you get into a Japanese bath?

What do you leave outside a Japanese locker room?

Why does everyone stare at you when you pour yourself a beer?

When does “yes” not mean “yes”?

What’s the polite way to eat noodles?

What’s the worst thing you can do with chopsticks?

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Watching Mr. Baseball again after a 20-year interval, I’d have to say it’s a pleasant confection, nothing more. The film does give the audience a glimpse into the fascinating world of Japanese baseball, and the leads—Tom Selleck, Ken Takakura, Aya Takanashi, Dennis Haysbert—suit their roles well. There are also some valid insights into Japanese culture, both on and off the ball field. But a great Japanese baseball film is going to have to be made by a Japanese director and feature the great Japanese players and teams. At the moment, I don’t believe such a film exists. I googled “Japanese films about baseball” and found a series of interesting posts at the JapaneseBaseball.com website. You’ll find the responses here:

http://www.japanesebaseball.com/forum/thread.gsp?forum=2&thread=30540

One of the most informative responses was from Animaru Resulie, who pointed out that there’s likely been a shortage of Japanese baseball movies because all of the creative energy has gone into baseball stories as told through manga and anime, where the possibilities are literally unlimited. Animaru mentioned that a Japanese Wikipedia article she linked to had a list of 300 baseball-related manga titles, a handful of which have been turned into movies.

It’s always a pleasure to watch veteran Japanese tough guy Ken Takakura. I first saw him in Sydney Pollack’s The Yakuza back in 1974, where he played with another veteran tough guy, Robert Mitchum. In 1989, he was a lead actor in Ridley Scott’s Black Rain. Takakura-san is the right choice to play a typical high-profile Japanese baseball manager—a good many of them have been larger-than-life and harder than nails.

Want to learn more? If I can’t steer you to a great Japanese baseball film, I can point you towards an awesome book on the subject: Robert Whiting’s You Gotta Have Wa. Whiting’s credentials are impeccable: he graduated from Tokyo’s Sophia University with a degree in Japanese government, he’s written five books in Japanese, has been a sports columnist for Japanese newspapers & magazines, and is an excellent storyteller. You Gotta Have Wa is not just the best book available in English on Japanese baseball, it’s also one of the most insightful explorations of some of the key cultural differences between Japanese and Western societies. The Tom Selleck quote above touches on one of the main sources of tension as it relates to sports. The Japanese see great baseball as the product of the kind of hard work and discipline that Olympic athletes demonstrate; Japanese ballplayers have been subjected to grueling regimens of hours of pre-game drills, draconian controls on their private lives, and a training schedule that run virtually year ‘round. Nothing, and I mean nothing—not even the birth of child or a parent’s funeral—supersedes a player’s obligations to the team. A related concept is that of wa, the ideal of group harmony that trumps individual grandstanding. The Nail That Sticks Up Shall Be Hammered Down. This is not a world that American or Canadian ballplayers can step into without either seriously re-evaluating their relationship to the sport or finding their contracts no longer desired. Tom Selleck’s character is hardly an exaggeration in his ignorance of Japanese norms or his outrage at his manager’s expectations. To use an example from Whiting’s book, Jack Elliott had nothing on real-life American relief pitcher Brad (“The Animal”) Lesley, who played with the Hankyu Braves for two years starting in 1986, and whom Whiting calls the most unusual player Japan had ever seen. The nickname says it all. Ironically, the Braves set a new attendance record in the Animal’s first year.

You Gotta Have Wa explores in detail the varying challenges faced by American professional players in Japan, the history and dynamics of the various teams, the different styles and philosophies of the managers and coaches, the training routines, the great stars of the Japanese baseball firmament, and the challenges faced by translators caught in the crossfire between irate or confused gaijin and samurai-heavy management.

An interesting side note to Mr. Baseball was the complete disappearance from the movies of the young actress who played Tom Sellack’s Japanese love interest. There’s a website dedicated to finding out why Mr. Baseball was virtually Aya Takanashi’s first and last movie. The link to The Actress Who Never Was or The Mysterious Case of Aya Takanashi is here:

There’s even a Canadian joke in Mr. Baseball. When someone floats the idea of playing for a Canadian team, Tom puts us in our place: “I ain’t paying those taxes!” Really, it’s not that bad. Check us out!