Before the curtain falls:

“Death is dark and quiet. No one will ever be able to get me. Hang a big sign on my neck—GONE FISHING. It’s my choice. Mama, I’m just not having a very good time, and I have no reason to think it’s going to get anything but worse. I’m tired, I’m hurt, I’m sad, I feel used….”

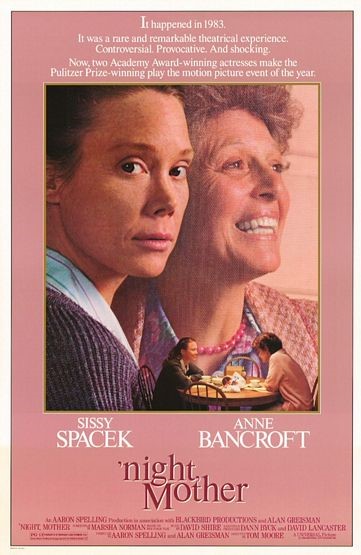

Two women, mother and daughter, in a very ordinary house. One single, extraordinary act. Eloquent voices speaking against a darkness that voices cannot keep from closing in. The basic ingredients for tragedy. No safety nets for either actors or spectators. Jessie (Sissy Spacek), the young girl in ‘night, Mother (1986)—epileptic, lonely, with a broken marriage and a son working his way through delinquency towards serious crime—is looking for a reason to stay around in this vale of tears. Her mother, Thelma (Anne Bancroft) can’t find it. You probably won’t be able to either. Sometimes lives are saved only by answering questions before they are asked. Jessie’s words are nails on her own coffin; they mean so much to us not because they heal, but because they help us to recognize the wounds. No one can heal what they are incapable of seeing. In a story filled with sad ironies, none is sadder than Thelma’s bewildered “I was here with you all this time—How could I know you were all alone?”

Jessie decides to control her life by controlling her death. She doesn’t look for pity. She doesn’t offer it. The knowledge that there’s a choice she can make that cannot be reversed, taken away, twisted, or denied gives her the only power she feels she’s ever had. Her mother watches with growing horror as Jessie meticulously sets the house in order for the life she know will go on without her, following the same predictable rounds it always has. Bills will have to be paid, the police will have to test for gunpowder residue, the laundry will have to be done. As Jessie turns the fierce, final light of truth upon her own past (the lessons her son has learned, she confesses, she has taught), the same fierce light burns across her mother’s memories. It is the cruellest and most total intimacy. There’s the daughter who asks, “What if you’re all I have—and you’re not enough?” and the mother who pleads, “I don’t like things to think about—I like things to go on.” Both can only wonder how each could have understood so little. Both finally come to terms with husbands who ended up draining their lives instead of enriching them.

‘night, Mother is powerful because it’s never morbid. No easy wash of sentiment excuses us from feeling the full force of what the characters are saying to one another. We can’t stop listening. The performances of Sissy Spacek and Anne Bancroft are utterly convincing. When Jessie says that she is feeling as good as she has ever felt in her life, we believe her against all odds. Borrowing the words of Willa Cather, from a story with a similar theme, ‘Night, Mother speaks to us of the vastness of things left undone.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

This is the way the world ends. With a bang and a whimper. Some rattling pots. Some anguish, some tears. Some regrets, some guilt. Some love that’s enough to hurt but not enough to heal. ‘night, Mother is one of the most heart-searing films I know. A tour de force in emotional wounding that never lets go. Sometimes people don’t rage against the dying of the light; instead, they step resolutely into the darkness. Those left behind wonder if anything they might have done could have held them back.

I still love this film. I probably cried the first time I watched it. I certainly cried when I watched it again before writing this reflection. By an odd trick of memory, the one line from the film I thought I’d never forgotten, “It’s just not fun anymore,” I didn’t get quite right. Jessie’s actual explanation for her meticulously planned suicide was “I’m just not having a very good time, and I have no reason to believe it’s going to get any better.” I recalled Jessie making the comment at the end of the film; in reality they’re spoken early on. They are for me the simplest and most profound accounting for terminal despair. One thing I hadn’t remembered was that Jessie says she’s made her decision because it’s the first time she’s felt in control of her life. It’s the first time she’s felt good enough to say No to the future. Most people try to find peace before they die—Jessie chooses death because she finds a moment of peace with herself.

When one knows where this story is going, the simplest conversation—about a towel, about a cancelled newspaper, about a vacation—takes on terrible weight. What also struck me this time around was how the accumulation of simple, harmless actions—making lists, writing labels on bags, filling cupboards, rolling up a tube of toothpaste—can be a kind of surrender to darkness. I’ve always told students to tackle daunting tasks one step at a time; Jessie applies that advice to the lethal letter.

Thelma Cates asks her daughter what happened at Christmas to drive her to her decision, and Jessie replies, “Nothing.” She freights that word with the emptiness that’s filled her life since her marriage failed, her son’s life unravelled, and she cut herself off from both work and society. That same little word, “nothing,” also opens up the soul-destroying void at the end of Ernest Hemingway’s “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” and the beginning of King Lear.

Marsha Norman did the screenplay for ‘Night Mother, based on her own 1983 Pulitizer-Prize winning play. Sissy Spacek and Anne Bancroft, alone onscreen for 99% of the film’s running time, could not have done a finer job bringing Norman’s drama to the screen. There’s not a single moment when I felt I didn’t know these two women from encounters in my own life. I find it difficult to understand how ‘night, Mother managed to not win a single award, anywhere. This was the same year that Blue Velvet walked off with a dozen major prizes. I’d say it’s because movies based on plays have a harder time of it, but Angels in America and Wit would make a liar out of me. Is it the subject that’s off-putting? Then why was Sophia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (1999) so successful?

I think even more highly of ‘night, Mother when I compare it to a film such as Ingmar Bergman’s Winter Light (1963). In the latter film, suicide is incidental to a philosophical/spiritual shipwreck. It’s collateral damage to a crisis of faith. We never forget that we’re watching Bergman think. There’s a moral lesson here. ‘night, Mother, on the other hand, is about Jessie and her mother—not the director, not the playwright. I don’t think you’ll find a moral lesson here. The only other movie I have seen that treats the same subject as unflinchingly is a short film by Julia Kwan, Three Sisters on Moon Lake (2001), included as a bonus feature on the DVD for Kwan’s Eve & the Fire Horse (2005).

Jessie grieves for the life she never had, referring to herself when she says, “Somebody I lost. Somebody I waited for who never came.” It’s not unhelpful to chart both Jessie’s and Thelma’s emotions against Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. The mother goes through all of them in her final moments with her daughter; the ultimate tragedy is that by the time Jessie and Thelma have their first meaningful dialogue ever, Jessie has spent 10 years getting to her interpretation of the final stage with no one knowing she was grieving. One last question: Can we interpret the fact that the last thing on Jessie’s list was “Talk to Mom” instead of “Leave a Note” as a plea for help, or as Jessie’s best way of proving to herself that for once in her life she was in complete control?

Listen for the lovely, minimalist score by David Shire.