Guido: You care—whatever happens to anybody happens to you. You’re really hooked into the whole thing. It’s a blessing.

Rosalind: People say I’m just nervous….

Guido: If it weren’t for the nervous people, we’d still be eating each other.

Gabe: What’s eating you?

Guido: Just my life.

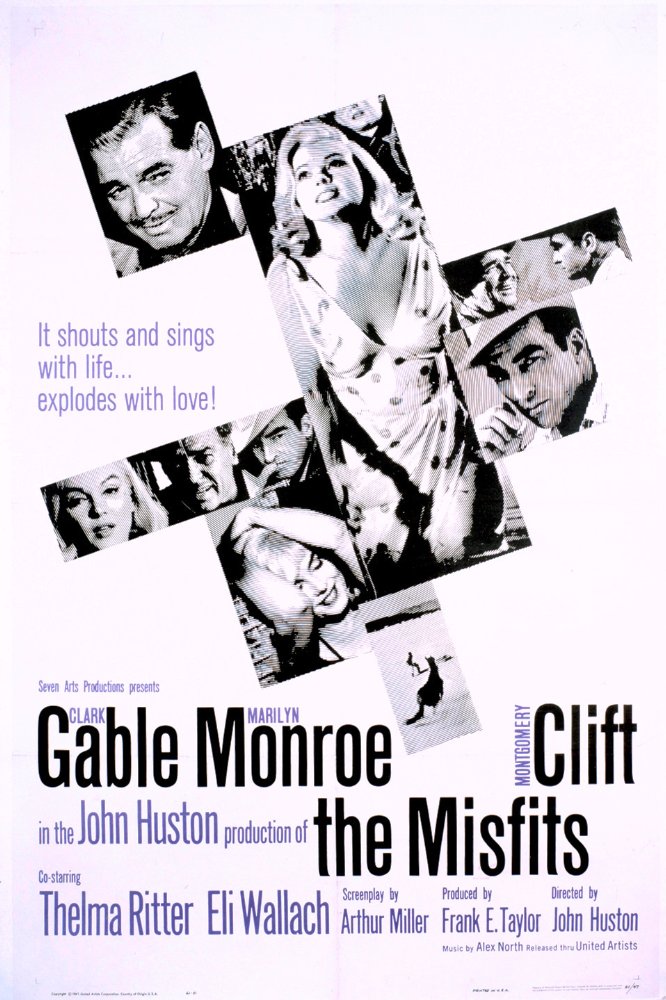

At a point midway through John Huston’s The Misfits (1961), Marilyn Monroe leans against the moonlit walls of a half-built home in the Nevada hills and whispers one word into the night: “Help”. It’s a powerful moment in a film with more than its share of them. It’s powerful for all the right reasons, and for all the wrong ones. The wrong ones are biographical. One can’t help wondering if in Marilyn Monroe’s own life, sometime, somewhere, a similar quiet plea went unheard or unanswered. A year and a half after the film’s release, she was the victim of a fatal overdose of barbiturates. No one watching The Misfits can divorce the actress from the role she plays here. And when one recalls that the film’s screenplay was written expressly for her by her husband, playwright Arthur Miller, life & art blur inextricably. The fault is history’s; everyone indulges in the wisdom of hindsight.

And the right reasons for the power of that scene in the Nevada hills? Purely dramatic. The character who talks to the darkness would haunt us every bit as much if we had never heard of the actress who incarnated her. Rosalind, a young Chicago woman in Reno for a divorce from an absentee husband, is a revelation. If Marilyn’s own story seems too often a magnet for pity, Rosalind’s is not. She is not a victim. She is not a martyr. She is not Florence Nightingale. She is not Mother Earth or the Eternal Feminine or an accommodating Venus. She is sexy, loving, generous, impulsive, childlike, radiant.

The men in her life are confused. They see everything that Rosalind is, and assume her to be everything that she is not. The source of confusion is simple. They fail to see the one quality she possesses that separates her from their fantasies: intelligence. When the husband she is about to divorce shows up on the courthouse steps looking for a last-minute, guilt-induced change of heart, Rosalind tells him exactly what kind of soulmate he’s been: “If I’m going to be alone, I want to be by myself.” Eli Wallach’s character, Guido, has such a hard time seeing Rosalind for the complete person she is that she has to nail him to the wall twice before he wakes up. I think the first time it happens he manages to shrug the moment off by refusing to believe that a woman who looks and acts like Rosalind does is capable of deliberate irony. The incident deserves elaboration. He’s just finished showing her around the unfinished house he was building for his wife, who died in childbirth. He tells her the entire story surrounding his wife’s death, including the fact that he couldn’t get help in time because he didn’t have a spare tire for the truck. He ends with a proud claim: “She stood behind me a hundred percent—as uncomplaining as a tree.” To which Rosalind replies: “Maybe that’s what killed her. A little complaining helps sometimes.” The look that Guido gives her when she says that is one of my personal Great Moments in Cinema.

Clark Gable’s character, Gay Langland, doesn’t always fare much better. To his praise of the dead woman’s heroic virtues, Rosalind counters with: “She was a real good sport. Now she’s dead because he didn’t have a spare tire.” That gets another interesting look. Gable is perfect as the kind of cowboy that all the classic country songs warn women about (“about as unreliable as jackrabbits”). Unfortunately for him, Rosalind is the kind of woman Lyle Lovett writes songs about (“She’s Leaving Me Because She Really Wants To”).

Although more sympathetic than Wallach’s embittered character, Gabe has as hard a time accepting that this new woman in his life is complex enough to surprise him. When Rosalind mentions that she never finished high school, Gabe’s reaction is an enthusiastic: “Well, that’s good news!” She calls him on that one, as she calls him on Guido’s wife, and on his facile comments on married life. And in the end, she calls him on what’s become of his cowboy’s dreams. Until he becomes involved with Rosalind, Gabe is able to muffle the nagging voice that tells him the world around him has changed too much, too fast. That the cowboy’s rallying cry of “It’s better’n wages” rings hollow when the wild mustang you sweat to break is going to wind up as dog food in Peoria. Gable’s actual age when he made this film (59) adds credibility to his portrayal of a man who’s lived too long and hard to make reconciliation with the new world order easy. Gable’s insistence on doing his own stunt work for the film may have even cost him his life. He died before he could even read the reviews of what may have been the best role of his career.

One critic complained that the final scenes of the mustang hunt are painful to watch. Damn right they are. So are Hamlet’s scenes with his mother and Ophelia. Gable thought his scenes were important enough to risk his health doing them right. He did them right. My memory paid its own tribute: having first seen The Misfits some dozen years ago, I would have sworn it ended with the capture of the horses and Rosalind calling Gabe and his fellow cowboys dead men. I’d completely forgotten that the movie actually ends on upbeat note.

Thelma Ritter and Montgomery Clift are excellent in supporting roles. Clift is particularly engaging as Perce Howland, an addled, much-injured, young rodeo rider who’s the only person not trying to make Rosalind part of an agenda. If Rosalind were really what other men see her as being, she’d have probably left Gabe to mother Perce on his crash & burn course through life. But she isn’t. And she doesn’t.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

I feel a bit like a voice crying in the wilderness on this one. I don’t think I’ve come across a single unreservedly positive review of The Misfits from a major critic. Too bad. My impressions haven’t changed. There may be some lines that don’t hold the weight they’re meant to carry, but the performances ring true. John Huston and Arthur Miller couldn’t have worked with a better cast for the story they had to tell.

Marilyn Monroe has been clinically dissected, mythologized, lied about, psychoanalyzed, and exploited more than anyone else in the history of the movies. Whatever one chooses to take away from the ever-growing stacks of serious biographies and trashy exposes that try to cast light on her life and career, one thing must be clear by now: Ms. Monroe was a very complicated young woman. The Misfits is my favourite Monroe film because it gave her the one role that allows her to show that complexity. As Roslyn Taber, she’s undeniably the kind of woman who could have seduced, fascinated, and disillusioned men as disparate in character as Joe DiMaggio and Arthur Miller. Miller wrote the film’s screenplay, and it would be hard to believe he wasn’t trying to come to terms with the woman he’d married. He apparently did the writing while he was in Reno waiting for his divorce from Monroe to be finalized. Miller’s screenplay captures Monroe’s childlike naivete and wonder, her sultry sensuality, her vulnerability, and her clear-eyed grasp of society’s uglier quid pro quos.

Some of Monroe’s sense of wonder must have come from acting with Clark Gable, whom she’d adored since her teen years. Gable is splendid as a ne’er-do-well, love’em and leave’em cowboy trying to hold on to some self respect in a changing world. He’s an old-fashioned romantic lead, and his chemistry with Monroe makes their age difference irrelevant. There’s more than one worm in passion’s bud, however. When Roslyn tells Gay that she never finished high school, his response is a grinning “That’s real good news!” She doesn’t miss the implications of that remark. This is the other Gay speaking, the one who can’t hold onto a marriage or a relationship, and has cut himself off from his own children.

Nor does Roslyn miss the subtexts of Guido’s self-pitying story about the death of his wife in childbirth. Her responses cut into on the underlying misogyny like a straight razor. They’re some of the best lines Ms. Monroe ever had:

Guido: She wasn’t like any other woman. Stood by me 100%, as uncomplaining as a tree.

Roslyn: Maybe that’s what killed her.

——–

Gay: She [Guido’s wife] was a real good sport.

Roslyn: Now she’s dead because he didn’t have a spare tire.

——-

Guido: [My wife] had no gracefulness.

Roslyn: Why didn’t you teach her to be graceful? If you loved her, you could have taught her anything.

——–

Roslyn: [referring to her soon-to-be divorced, absentee husband] If I’m going to be alone, I want to be alone by myself.

And then there’s the story she tells of the “loving” husband who propositions her while his wife is in the hospital having their first child. That may be Roslyn speaking, but is there anyone who’d doubt that Marilyn Monroe’s life didn’t have more than one of those supremely disillusioning moments? And how many times can you become disillusioned before you simply stop believing in anyone, including yourself?

Near the end of the film, Rosalyn asks the question “How do you find your way back in the dark?” For Marilyn Monroe, the answer seems to have been, “Sometimes you don’t.” I wonder if part of the weight she carried near the end of her short life was that of Clark Gable’s death of a heart attack shortly after the completion of The Misfits. Although a last triumph for both Monroe and Gable, the production had been a difficult, troubled one and may have triggered Gable’s heart attack. He never saw the finished film, nor did he live to see his only child, born several weeks after his death. [From Anthony Summers’ Goddess: Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe—“Clark Gable himself, the quintessential professional, realized Marilyn’s worth as an actress. He would live long enough to tell his agent, George Chasin, that working with Marilyn on The Misfits resulted in one of the very best of his seventy films. It was also Gable’s turn to ask, ‘What the hell is that girl’s problem? Goddam it, I like her, but she’s so damn unprofessional. I damn near went nuts up there in Reno waiting for her to show.’”]

Montgomery Clift, Eli Wallach, and Thelma Ritter round out a strong cast. Estelle Winwood has a great little walk-on role as a church lady that would give the Devil pause. They could have given her a movie of her own. Ritter’s character, Isabelle, sports the kind of defensive armour—self-mockery, wit, reduced expectations— that Roslyn is incapable of donning. Isabelle rolls with the punches. She can comfortably socialize with her low-life ex-husband and his new wife. Roslyn can only see a culture that grinds women down, that convinces cowboys that rounding up wild mustangs for dog food is what a man’s gotta do.

For the second time, I forgot that The Misfits had a happy ending. Rosalyn and Gay remain together; Perce heads out to pick up the pieces of his life. Guido gets his just desserts. Somehow, though, knowing what is to come for Gable, Monroe, and Clift, the sadness seems to drift back in as soon as the screen goes dark.