“My life would make a damn good country song.”-D. Fritts

“He who controls rhythm/controls”-Charlcs Olson (both quoted in Nick Tosche’s Country)

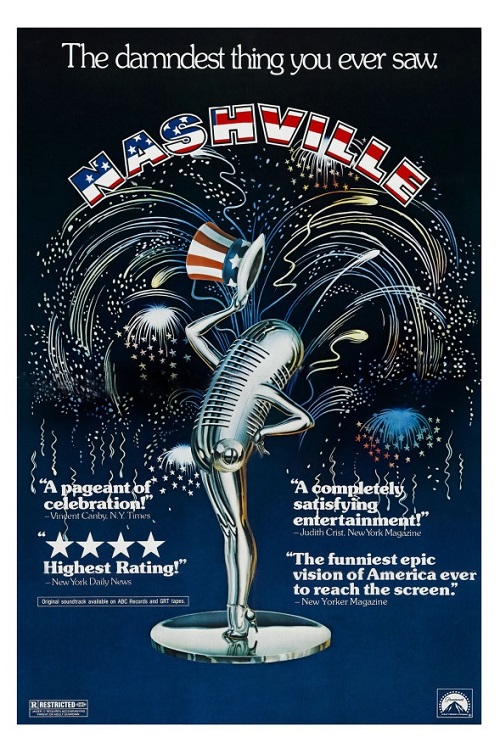

A Woodstock for the mid-1970s? In Tennessee? It’s hard to find single films which capture the essence of an entire era the way director Michael Wadleigh’s Oscar- winning documentary did for that 1970 mother of all festivals in Bethel, New York. One such film did, however, find its way into my VCR this month: Robert Altman’s Nashville.

Wadleigh had it easy. After all, he didn’t have to create Woodstock—just be talented enough to capture it on film. Robert Altman invented his own pivotal moment in the life of his country. From scratch. History made, rather than history found. Nashville is a unique motion picture, both in its genesis and its broad vision of America. If Bob Johnstone ever had the chance to produce a 159-minute Today in History for PBS, it might look something like Altman’s film.

For those of you out there enthusiastically following the recent renaissance in country & western music, Nashville’s the picture to see. For those of you out there with an utter loathing of country music, who see it as a shrine to emotional pornography, jingoism, & Sunday School hypocrisy, Nashville’s the picture to see. It’s big enough, wise enough, generous enough to take on all comers.

Let’s start with the film’s 24 main characters. If not a Guinness record, at least close to it. In a display of virtuoso narrative legerdemain, Robert Altman weaves all 24 characters into a screenplay which manages to do justice to each of them while dispensing with plot. The actors were equally generous with Altman. All of them agreed to work for the same salary on this project. Hard to believe in this age of mega-salary one-upmanship. The eleven and a half hours of finished film that Altman shot for Nashville was done on a $2 million budget over a mere 45 days. If the climax of Nashville is the American nightmare, the movie itself is a child of the American dream. Three years later, Hollywood would spend $100 million on Superman, $2 million of which would go to Marlon Brando for a cameo appearance.

Each actor in Nashville brings total conviction to his or her role. As the audience, we are almost immediately caught up in the flow of these multiple lives. There is little confusion at the beginning of the picture; none at its end. And how fitting that the initial backdrop for the introduction of the cast should be a traffic jam on the freeway. Unlike French director Jean-Luc Goddard’s use of a traffic jam (in Weekend) as a kind of surreal guerrilla theatre and anticapitalistic diatribe, Altman sees it as perversely democratic. In North America, the highway is the one metaphor we all share.

Three of my favorite performances in Nashville are those of Lily Tomlin as a devoted mother tempted into a one-night stand with a predatory musician, Keenan Wynn as the distraught uncle of a young woman who takes juvenile selfishness to new heights, and Henry Gibson as a bespangled, very convincing country music star à la Hank Snow. The reactions to Gibson’s character on the part of critics was a microcosm of the larger battle over country music itself. Shallow, excruciating & vainglorious. Sincere, moving & selfless.

The cast made their own judgment about the music. They wrote it (as they did much of the dialogue). Probably another motion picture first. Virtually every song in Nashville was written, in character, by the actor who performed it. New York critic John Simon said that that just proved that country music was so bad even amateurs could do it. Bulltwaddle. With the help of composer Richard Baskin (who does a cameo as the rock ’n’ roll piano player Gibson fires in the opening scenes), the actors obviously cared enough about the music and their characters to try to make them both their own. They were taking their cues from the seriousness and respect with which the best country & western musicians treat their lyrics and their audiences. Don’t get me wrong, though. Had there been anything like Merle Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee” on the soundtrack, this review might never have seen the light of day. Some sins are beyond redemption.

Set during the weekend of both a fictional Tennessee presidential primary race, and a major country music rally in support of one of the candidates, Nashville was an uncannily prescient film. Throughout, the mobile sound van of unseen candidate Hal Phillip Walker and his Replacement Party blares out sound bites of the populist demagoguery that would blossom later into the real-life candidacy of Ross Perot and the resurgent American Right. As one of Walker’s key campaign organizers, actor Michael Murphy epitomizes the triumph of sleaze over substance. We now find ourselves living in a time when the Replacement Party is being swept into power across North America. Voting is ceasing to be the expression of common democratic ideals; those ideals are being supplanted by the politics of disgruntlement and self-interest.

Nashville is also about the cult of celebrity in America: how it simultaneously idolizes and demands ritual sacrifice. Barbara Jean (played by Ronee Blakley, who later that year would tour with Bob Dylan), the reigning country music queen, is willing to sacrifice her own health in an honest desire to satisfy the hunger of her fans. There is no falsehood in her. Her fans worship her, but with the most primitive instinct of the pack, they turn on her in a moment of weakness. Another fan slips into her hospital room for an all-night vigil, ultimately harmless but potentially terrifying. In the end, the sacrifice is accomplished. The real-life scenario would play itself out ten years later in front of John Lennon’s New York apartment.

By the way, for those of you who watch Altman’s film and can’t figure out what the guy on the motorcycle is doing, I think I have the answer. He’s in Nashville for the same reason the Parthenon is. America is just that kind of place.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Nashville impressed me as much this time around as it did so many years ago. I really don’t feel the urge to add much more to what I wrote in my original review. If I wished to do more than Roger Ebert did in his typically, maddeningly insightful essay on Nashville in the first volume of his Great Movies series, I’d have to watch the film a couple more times and take a whole lot of notes. I’m not up for it. I’m content to just marvel at how quickly the 160-minute running time went by, and how intimately the viewer comes to know the 24 characters whose lives director Robert Altman and screenwriter -Joan Tewkesbury manage to weave together over the course of a five-day timeline. It’s magic. Although I’ve got my favorites (Henry Gibson, Ronee Blakley, Shelley Duvall, Barbara Harris, Gwen Welles, Keenan Wynn), there isn’t a single one of those 24 performances I’d want to see cut. Even Geraldine Chaplin’s insufferable BBC reporter (is she really who she claims, or just a nutcase with a tape recorder?) gets the perfect line to expose her own utter lack of empathy when she dismisses an overeager chauffeur with, “I don’t listen to gossip from the servants.” About what you might expect from a reporter who doesn’t even know what gospel music is.

Altman took a huge gamble in having his actors write their own songs. The potential for that going sideways must have cost him a few sleepless nights. Of course, the gamble paid off. And Altman had enough respect for the actors to let them perform full-length versions of their songs. No splicing in a chorus or a single verse and rushing on. The characters are their songs. Music is the fourth dimension here. There may be a lot of jingoistic and hypocritical moral pandering in country music, but no one doubts Johnny Cash when he sings “Folsom Prison Blues,” Loretta Lynn when she sings “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” or Dolly Parton when she does “Coat of Many Colors.” Henry Gibson & Richard Baskin’s “200 Years” is the pitch-perfect song to open the film, and Keith Carradine’s “It Don’t Worry Me” the perfect one to close it. Nashville is one film I look forward to sharing with my Hamilton-loving grandchildren just because it’s so much not their world.

Robert Altman apparently developed a whole new way of recording sound for his films, that allowed for the overlapping voices and background sounds that characterize much of his work. I have yet to find a clear description of how he worked this, other than that the actors were individually miked during filming. This is where the creative use of technology creates textures that affect the audience on a subliminal level. One outrageous example is when a jumbo jet lands in the background right in the middle of the scene of Barbara Jean’s publicity-hyped arrival at the airport. How many other directors would choose to punctuate this kind of dramatic moment with the sound & sight of a jet engine?

It’s interesting to see how far off the mark the populist message of Nashville’s Replacement Party is from the current reality of American parties. If anything, Donald Trump is the anti-Hal Phillip Walker. Cancel the tax-exempt status of churches? Drop corporate subsidies? Get the lawyers out of Congress? Not on President Trump’s watch. Populism has been swallowed up whole by Wall Street, the Pentagon, master classes in propaganda & disinformation, and plutocrats with more personal wealth than half the world’s nations. The only thing that’s been “replaced” is any sense of community. We were worried about George Orwell’s 1984; we should have been paying more attention to Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead.

I’d say that Nashville is timeless—despite the hair, the clothes, the cars—but something has indeed changed in the last 30-odd years. Now it’s not the death of a public figure that we fear at the hands of the lone, crazed assassin. The new reality is that it’s the public itself that’s in the crosshairs. Whatever progress we’ve made in this world, mass shootings are not a part of it. This new spiral into violence may have been inevitable. The last century saw civilians replace soldiers as the frontline victims of war; in the 21st century, the psychopaths and fanatics are showing us that they’ve been paying attention.