“You killed my master! Now, you die!”<primal screech of rage, followed by loud slapping noises>

–a very brief summary of Hong Kong martial arts cinema, taken from A. Magazine’s Eastern Standard Time

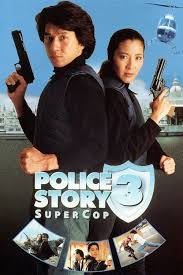

Movie reviews tend to be inspired by things like stunning cinematography, superb performances, and unforgettable story lines. There are exceptions. This particular review of Jackie Chan’s Supercop (1992, aka Jing cha gu shi III: Chao ji jing cha for you purists; also called Police Story 3) was inspired by, well, a shopping cart. Not even an armored, machine-gun mounted, turbo-charged, customized James Bond-type shopping cart. Just your average Overwaitea, what’s-next-on-the-list-dear buggy. And it’s not even in the movie.

Let me explain. Several years ago, I caught an episode of Siskel and Ebert at the Movies in which Roger Ebert demonstrated, incredibly effectively, what really made Jackie Chan one of the most popular movie stars in the world. Rather than choosing one of Chan’s dozens of literally death-defying stunts, which tend to dominate discussions of his career, Ebert did a slow-motion replay of a 5-second action sequence (from Rumble in the Bronx) in which Jackie Chan dove into and through a shopping cart while escaping an attacker. It was the kind of phenomenal demonstration of speed, agility, strength and grace that I hadn’t seen since my last Buster Keaton binge. Or maybe my last Fred Astaire movie. My jaw on the floor, I knew at that moment that I’d be seeing a lot more of Jackie Chan in the future.

I have indeed. Worldwide, he is the most widely-recognized actor of his generation. In 1996 in Hong Kong, nine of the ten top-grossing films featured Jackie Chan. There is no one out there who makes a more inspired use of physical props; he can do more things with a chair or a jacket than a lot of movie makers could do with an entire Special Effects unit. Not bad for a guy with one year’s formal schooling, who’s whole career has centered around martial arts slugfests with plotlines pretty well summed-up by the quote above.

Jackie Chan has earned his status. Like Buster Keaton, as a young boy he survived a school of very hard knocks to ultimately triumph as a Clown Prince. With a self-deprecating humor that’s his answer to Keaton’s “great stone face”, Chan pushes the limits of the physically possible as fearlessly as Keaton once did when he rode a motorcycle backwards, standing up, over a collapsing bridge.

Jackie Chan refers directly to Buster Keaton in his recently-published autobiography, I am Jackie Chan. It’s an excellent book for anyone who’s a fan, and for anyone who’s a sucker for martial arts movies. I happen to fall into both categories. I’m really good at rationalizing it all by saying that it’s a cultural experience.

It is. Really. A Chinese friend of mine, in my first years at university, would take me down on weekends to the Chinese movie theatres on Granville & Main or Hastings & Nanaimo in Vancouver. I’d see absurd stories on cheesy sets with kung fu monks making twenty-foot leaps into the air and striking down dozens of nastily-stereotyped evil Japanese villains with the incomprehensible Secret Fist of the Crane Flying Upside Down. My friend Raymond would see elements taken from classical Chinese opera, dozens of actual kung fu moves that he’d studied back in Hong Kong, historical characters of which I was utterly ignorant, decades of Japanese oppression of the Chinese mainland, and period details of costume and setting as rich as the special effects were laughable. Those evenings at the Shaw were multiculturalism at its best. Although I probably saw some of Jackie Chan’s earliest films back in those halcyon days, the real star then was the tragically short-lived Bruce Lee.

Reading I am Jackie Chan and watching Supercop (and, in the interests of research, New Fist of Fury, Snake Fist Fighter, Who Am I? and Police Story), it was great to be back in a cinematic world which owed little to Hollywood and its values. I choose to focus on Supercop in particular because it’s a perfect contrast to what goes on in most American action films. Take the first fifteen minutes of Supercop, for example. Nothing happens. No fighting. Nothing blows up. It’s a running joke introducing Chan’s character. The people who dubbed the film made it even more of a joke by deliberately mismatching voices and giving some actors more lines than their mouths can handle (Chan and his co-star Michelle Yeoh dub their own voices).

Jackie Chan never swears. Even the bad guys have to settle for “hell” and “damn” under extreme duress. Nobody uses the Lord’s name in vain. There’s no sex. No dirty jokes. There is violence, heaps of it, but there’s no gore. Picture WWF wrestling or Scarface scripted by Monty Python.

Hong Kong production budgets don’t allow for special effects created in high-tech labs. The motto might be: “Cheap, fast, and under control.” Everything happens live. The actors, stuntpersons, and explosives people do all the work. The budget for Supercop was $15 million; compare that to Mission: Impossible’s $100 million. Guess which one’s more entertaining?

Too often there’s a grimness about American action pictures that clings to the psyche like stale smoke in a bar. Even in Jackie Chan’s earliest kung fu movies, before his humor was given free rein, no one was trying to fool us into thinking that what we were watching was anything but staged. About the time Bruce Lee became a star the actual fighting sequences became much more realistic (a key factor in Lee’s appeal), but villains still indulged in maniacal laughter as soon as they ran out of dialogue, people caught knives in their teeth and spit them back at opponents, and laws of gravity and physics were routinely violated.

Ironically, these films also featured female roles that were stronger than anything in their western counterparts (with the notable exception of Sigourney Weaver in the Aliens series). Where the James Bond pictures specialized in women as eye candy, and countless others exploited them as victims, the “chopsocky” films had them truly standing by their men—kick for kick, punch for punch. Chan’s co-star in Supercop, Michelle Yeoh (billed as Michelle Khan) also matches Chan stunt for dangerous stunt. She hangs onto a speeding van for dear life, jumps a motorcycle onto a moving train, and demonstrates some amazing martial arts moves. All this from an actress who was originally a Malaysian beauty queen, trained in classical ballet.

And there’s another irony. Jackie Chan credits where he is today to the ten years of brutal training he had in Master Jim Yuen’s Chinese Drama Academy in Hong Kong. It’s a Dickensian tale of beatings, vicious rivalries, and relentless conditioning. Young people who watch Jackie Chan in action today should know that at least some of his genius is the product of a system that would appall both them and their parents. The Academy-trained students, who lived there for years with minimal contact with their families, for the incredibly demanding roles of the Beijing opera. These roles required acrobatic skills, singing skills, ability to handle weapons, comic timing, and makeup artistry.

Unfortunately, by the time Chan was ready to leave the school, the Beijing opera was a dying art form. As it disappeared, Hong Kong cinema rose from its ashes. Graduates of the drama schools were eagerly snapped up by the Shaw and Golden Harvest studios.

Jackie Chan does not believe that he would be where he is today without his trial by fire under Master Yuen. With the passing of institutions such as the China Drama Academy, he doesn’t believe the current generation of actors can achieve the intensity of his own generation. I think he’s mistaken. The aspect of his films that he’s most famous for—doing his own extreme stunt work at the risk of serious injury and death—is the one aspect of his stardom I’m least comfortable with. I don’t want any actor taking those kinds of chances for my “entertainment”. I don’t like feeling like a ghoul. A guy with a wife and 15-year-old son has no business jumping from a rooftop in Kuala Lumpur onto a rope ladder hanging from a helicopter hovering 10 stories about the ground. Jackie Chan needs only look again at three of his greatest role models: Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Fred Astaire. Their finest moments are more zen than mayhem. Michelle Yeoh had no martial arts training before she started working in the movies. She just fakes it, beautifully. What we really want is to be entertained by performers who, through sweat and dedication, astonish us by showing us what we can become at our finest.

It was once thought that circuses drew crowds because their acts were “death-defying”. High wires without a net. Lion tamers. Canada’s own Cirque du Soleil put an end to that myth once and for all. It’s time Jackie Chan lays his own myth to rest. I’ll remember that shopping cart a lot longer than I’ll remember the helicopter.

(Don’t forget to watch the outtakes included at the end of most of Chan’s films; they make it obvious how difficult some of the stunts really are. You should try to find some unedited, letterboxed versions if you can. The American distributors cut half an hour out of Supercop, re-edited some of the fight sequences, and added a soundtrack with Tupac Shakur, Tom Jones, and ‘Staying Alive’. And it’s still a great flick!)

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

With a dozen Jackie Chan films in my home collection, and easy access to so many others through venues such as iTunes, I was surprised and disappointed to find that Police Story 3 wasn’t readily available on a digital platform. Rather odd, considering that Police Story and Police Story 2 are out there, along with all of Jackie’s more recent films. What kind of black hole has #3 fallen into, and why?

No use crying over spilled milk, however. I just dipped into my own Jackie Chan collection and kept track of the some of the highlights (and lowlights) to pass on to you here. At the same time that I was watching, or re-watching, these films, I also was re-reading Jackie’s autobiography, written when he was in his mid-40s. Written in collaboration with Jeff Young, it’s a convincingly honest, insightful, and well-written examination of how a star is born. The book is also an excellent introduction to facets of Hong Kong filmmaking, to the rigors & rewards of a life dedicated to pushing personal limits, to the challenges & dangers of HK-style stunt work, to the impact of Bruce Lee’s films and his death on the martial arts, and to the importance of icons like Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and Fred Astaire in shaping Jackie Chan’s vision of what action cinema could be. I’ve attached several passages from Jackie’s book to the end of this review. I happened to be reading a biography of Babe Ruth at the same time, and was struck by the similarity in the way that both of these superb athletes had been sent away from home at a young age to institutions where they spent much of their youth and in which they were fortunate enough to find a mentor who would bring their talents to the fore.

What anyone who watches a good selection of Jackie’s films will invariably take away is a full appreciation of the incredible level of skill, strength, grace, and creativity that went into many of the fight scenes and action sequences. Police Story is one of Jackie’s own favorites, and with its downhill demolition derby through a shantytown, the Buster Keaton-inspired bus chase, and the jaw-dropping 15-minute glass-shattering finale in a shopping mall, it’s not hard to see why. And if you think that the fake glass they use in movies isn’t dangerous, in Police Story they doubled the thickness of the fake glass to make it even more realistic. Several stuntmen were injured making this film, and the lesson that Jackie took away from the experience was that he needed his own dedicated team of stuntmen that he could bring with him to all of his future films. He would know their capabilities and they would understand his expectations. I still stand by the wish I expressed in my original review of Supercop, that Jackie Chan not endanger his life for our amusement, but after a second reading of his autobiography I better understand that this is the path he has chosen to fulfill his dreams. He himself has sometimes wondered if things could have been otherwise (see one of the excerpts below), yet stands by his choices. For myself as a moviegoer, I’m giving a shout out to North American filmmakers for putting a premium on safety over thrills. No one needs to risk death to entertain me. If this means we’ll never rise to the daredevil heights of Jackie Chan (or Buster Keaton in the old days), so be it.

Enough sermonizing. Let’s rock! In Police Story 2, Jackie weaponizes an entire playground to take down a dozen thugs, and has another harrowing bus ride that actually ended with him diving headfirst through the real glass panel of a balcony instead of the fake glass one beside it. And speaking of weaponizing a playground, one of my greatest pleasures in watching these films is seeing how Jackie and his fellow actors take everyday objects and turn them to extraordinary uses. This was also part of the genius of the great silent comedians that Jackie admires. And check out Fred Astaire dancing with a hat rack in Royal Wedding.

City Hunter (1993), based on a Japanese manga, is the Jackie Chan equivalent of Austin Powers. It’s not really to my taste, I find the humor way too broad, but his female co-stars (Chingmy Yau Shuk-ching, Kumiko Gotoh, Joey Wong, Carol Wan) are all drop-dead gorgeous. I don’t know if there is a more perfect Jackie Chan moment than the one where he catches Chingmy, dressed like Lara Croft, when she jumps off a balcony, then spins her around in his arms while she guns down bad guys with two thigh-mounted handguns, and end the sequence by setting her on her feet and doing a couple of quick ballroom dance moves with her. My remote control’s rewind button got some serious work on this scene.

New Fist of Fury shows how desperately HK filmmakers wanted to resurrect Bruce Lee. Jackie had worked as a stuntman on the original Bruce Lee Fists of Fury, and did his best here to live up to expectations, but he realized early on that a refusal to innovate was a weakness of HK cinema at the time. With Lee’s death, the philosophy of “It worked once, so let’s do it over and over again” was a dead end. New Fist of Fury was a direct rip-off of the original, complete with hated Japanese oppressors, slimy collaborators, rival kung fu schools, and a venerated teacher to be avenged. Some good action, but both the blatant anti-Japanese messaging and the truly bizarre ending will leave anyone who’s not familiar with HK films from this period a little bit gobsmacked. As for the revolutionary Fists of Fury technique introduced here, here’s one reviewer’s comment: “Jackie’s Fist of Fury technique…involves waving his arms up and down slowly during funky 70s hypno-music. Deadly indeed.”

When Jackie became one of the biggest stars in Asia, studios were quick to exploit any product they could get their hands on that featured him in even the most incidental way. The 36 Crazy Fists (1979) was billed as a Jackie Chan movie although he only choreographed the stunt work and didn’t appear in the film. In The Killer Meteors (1977), Jackie plays the villain for first time, to his eternal regret. At the same time, however, we here in the West also got to see much cooler work such as Drunken Master (1978) and The Young Master. The latter film is filled with clever fight sequences using fans, swords, ropes, skirts, a long smoking pipe, and dueling benches. In other words, skirt fu, rope fu, bench fu, fan fu. It’s all a joy to watch. What you may not know is how hard the actors worked to pull off what you see on the screen. The fan fight scene took somewhere in the neighborhood of 329 takes. Jackie’s sparring partner co-star in The Young Master was Yuen Biao, one of his “Opera brothers” from his 10 years in a traditional Chinese opera school. The villain was played by Whang Inn-sik, a Korean Hapkido grandmaster, who also gets to engage in (not my words) “some dastardly moustache twirling.” Their final battle is over 10 minutes long. Jackie takes an incredible amount of punishment. The Young Master was the second film that Jackie directed, his first for the Golden Harvest production company, and the first film in which he got the chance to sing (during the closing credits).

In closing, here are some excerpts from Jackie Chan’s autobiography:

“As students left one by one and the academy faded away, there was no putting off the inevitable. The old performing gigs that Master had been able to rely one—the weddings, the festivals, even the Lai Yuen Amusement Park—were disappearing one by one. Other schools were closing, and professional opera troupes were disbanding; the trained and talented men and women who found themselves cut loose from their art had nowhere else to go but the movies. Me and the remaining older brothers had been working for several years at Shaw Brothers and other studios as junior stuntmen. But the dumping of so many experienced opera performers into the film industry meant that there was suddenly much more competition for every job.”

“Hong Kong’s biggest studio at the time was owned by the Shaw Brothers, Run Run and Runme Shaw—two of Hong Kong’s first tycoons. It was called Movie Town, and it was huge, over forty acres in size, with hundreds of buildings ranging in size from prop sheds to giant soundstages and dormitories for actors who were working on contract for Shaw Brothers. It even had a mock-up of an entire Ch’ing dynasty village, which served as the set for most of the Shaws’ movies—since most of the films they were making at the time were period martial arts epics and swordsmen films.”

“I look at films by Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin, Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire, and I say wow. These are classics, and they are great even today….

The early silent greats were comic pioneers, setting a gold standard in screen humor for everyone who’s followed since.

What people forget sometimes is that they were also, in some ways, the first action heroes. Without special effects and without stunt doubles, they did amazing things, falling and flying, climbing and tumbling, using their bodies to make miracles on screen.

I’d gotten hooked on the old silent because much of the story was told physically, which meant that, despite my limited English, their antics were as funny to me as they must have been to their original audiences. Maybe funnier, because I understood what it took to make them happen.”

Bruce [Lee]’s movies are like seeds that never had the chance to sprout.

I’ve had a much longer career, and I’ve made movies that I think I can be really proud of. I don’t know whether they will be seen as classics after I’m gone; I guess history will answer that question.

Even today, however, people try to compare us, me and Bruce, and make it seem as if we were competitors.

Nothing could be more ridiculous. There were things he could do that I couldn’t do; there are things I can do that he couldn’t do.

But you know, I never wanted to be the next Bruce Lee.

I just wanted to be the first Jackie Chan.”

“Bruce’s martial arts were tightly controlled, a compact whirlwind of energy that could be captured in a single master shot. But my style was wilder, more open, and acrobatic. As my films became more sophisticated, I found myself running through fight sequences in two, three, and four separate takes, shot from different angles, to get every facet of the intricate choreography on screen.”

“Now, these days, I’m known in Hong Kong for taking a long time on my productions; usually, the best I can do is turn out a movie a year, because I want everything to be perfect. It takes twenty years to raise a child, right? So one year to make a movie isn’t that bad….

When I’m doing a movie in Hong Kong, I make sure that every shot is perfect—that it follows the rhythm of the fight, that it properly captures the flow of the choreography. I plan the action. I supervise the editing. I hire the fighters and stuntmen. [I’m the lighting director and the director of photography. At the end of the day, I watch all of the dailies and plan out what we’ll shoot tomorrow. At the end of a shoot, I take the footage and edit it, scene by scene.] I can make sure that what I see in my head comes out on the screen. In my Hollywood movies, I never had that kind of freedom or that kind of control.”

“I don’t have anything to prove anymore. I’ve accomplished just about everything ‘ve ever wanted to, and more. But I say this as someone who know from experience: the farther you run in a certain direction, the harder it is to go back and start over.

I wonder to myself sometimes, if I could turn back the clock, whether I’d make different choices in my life. Would I spend more time and energy with my loved ones, my family?

Or would I follow the path I took—the one that led me here, fulfilling my hopes and dreams, at the expense of my heart?

I’m married. I have a teenage son. But working as I do, I haven’t ever been able to fulfill my duty as a father or as a husband. I spend two-thirds of my time abroad, and even when I’m in Hong Kong, my schedule is so full that I can barely find time to be with my wife and child. They understand—but I know they wish I could be with them, and I know my son would have loved to have had his father with him growing up. I’ve been able to provide for them well, but I know I owe them much more.

I’ve always tried to live my life without regrets.

I’ve done what I’ve set out to do, and I’ve had to make sacrifices to get there.

But still—sometimes I wonder.”

“Project A was…the first film in which I did something that has since become my signature:

The really, really, really dangerous stunt.

The superstunt has become the thing that makes a Jackie Chan movie unique. People come to see my films in part because they expect a fast-paced and funny experience. But the truth is, lots of films are exciting and hilarious. A Jackie Chan movie has something else: the thrill of high risk.

No blue screens and computer special effects.

No stunt doubles.

Real action. Real danger. And sometimes, real and terrible injury.

In shooting my stunts, I’ve hurt myself in hundreds of ways and nearly died dozens of times. People have called me crazy, and maybe they’re right, because you need to be a little crazy to do the things I do. Which isn’t to say that I don’t know the meaning of the word fear. I’m terrified every time I have to put my body on the line, but somehow, I still manage to do it anyway.