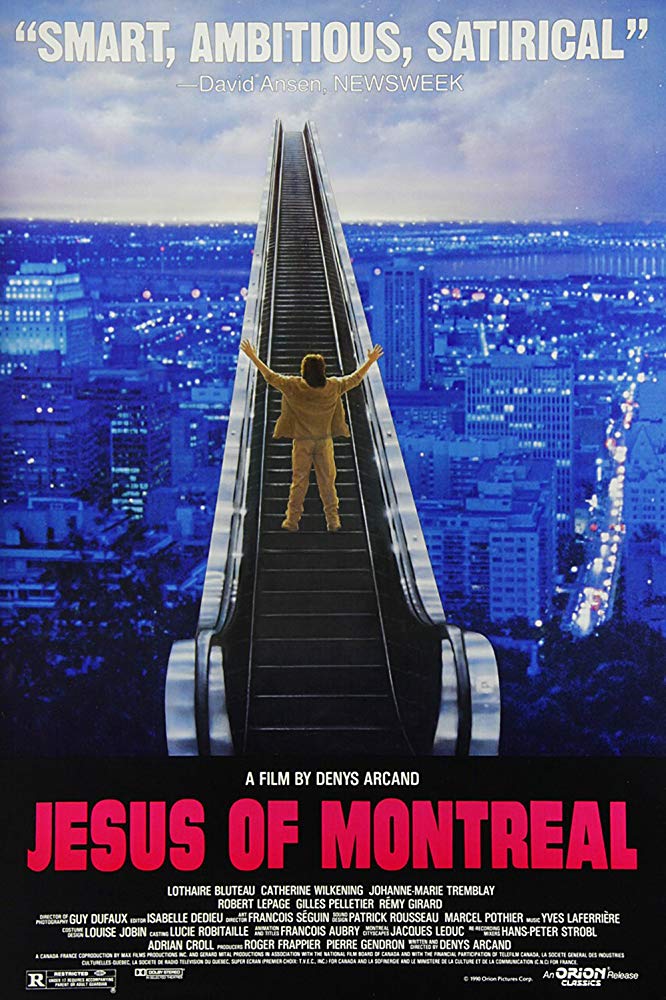

Early on in Denys Arcand’s Jesus of Montreal, René (played by the phenomenal Québecois stage director Robert Lepage) warns fellow actor Daniel (Lothaire Bluteau) that performing tragedy is dangerous. René is probably thinking of all the superstitions surrounding productions of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, a play with such a string of unfortunate accidents associated with it (coronaries, riots, collapsing sets, broken legs, etc.) that to this day in interviews on radio and television actors will use euphemisms such as “The Scottish Play” and “That Play” rather than say the “M” word in public. If performing the story of an obscure but blood-tainted Scottish king is so risky, how much more dangerous must it be to act out the harrowing life story of one of the most influential prophets and teachers of all time? Unfortunately for Daniel, his friend René’s concerns turn out to be justified.

At the beginning of Jesus of Montreal, the young actor Daniel is asked by Father Leclerc (Gilles Pelletier), a priest associated with Montreal’s grand Oratoire St. Joseph, to stage a new version of the traditional Passion Play. Passion Plays are one of our older forms of drama; they began in the Middle Ages and tell the story of the suffering, death, and Resurrection of Christ through a blend of readings from the Gospel and poetical commentaries on Jesus’ life and teachings. In the 13th C. they became such elaborate spectacles that they could last more than a week. They continue to be a part of the Easter worship into the twenty-first century. Father Leclerc would like Daniel’s help because after some 35 years his church’s particular version of Christ’s passion is losing its appeal and its audience. Daniel is pretty much given carte blanche to find a way of winning back the public.

Daniel turns out to be the perfect choice. He’s just finished a role in a dramatized version of Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, one of world literature’s greatest explorations of the nature of faith. Daniel is a very serious, very dedicated young man. Like so many people are doing with renewed passion today, he researches Christ’s era, His life, and His teachings. He haunts libraries for the latest archaeological and historical discoveries which help him understand Jesus’ life within the context of the time and place in which He lived. But form the moment he accepts Father Leclerc’s commission, Daniel’s life begins to change. He begins to literally walk in Christ’s footsteps.

Daniel’s first act is a renunciation of the modern world: by opting for the Passion Play he turns his back on an advertising hack who wants to promote him in high fashion ads as the archetype of l’homme sauvage, the new, leaner macho man.

Next, his search for a small group of actors to work with him on the play re-enacts Christ’s search for His disciples. Four young actors, two women and two men, help Daniel establish is own community of the faithful. For him, they will abandon their previous lives and defy authority. These are modern times, and for a symbolic Last Supper they will all share take-out pizza on the grounds of the Oratoire.

Daniel’s Mary Magdalene is Mireille (Catherine Wilkening). A former lover, she is a down-on-her-luck actor who’s finding some purpose in her life working in a soup kitchen. Mireille invites Daniel, who seems disconnected from family and friends, to stay with her and her young daughter. One of the first discoveries Daniel makes is that Mireille’s current lover is the very priest who has hired him to perform the Passion Play.

After Daniel, Father Leclerc is the film’s most fully realized character. The way that director and writer Denys Arcand handles human frailty is one of the things I most appreciate in Jesus of Montreal. There is nothing sensationally scandalous about Mireille and Leclerc’s affair. It is not there in the film to “expose” hypocritical priests or “unmask” libidinous depravities

lurking in confessionals. People are weak. People sin. Arcand wants us to understand Leclerc, not rail against him. Leclerc is a bad priest; he is not a villain.

He became a priest at 19 because his family was poor and it seemed his only option at the time. In the seminary, he was a bit of rebel, trying to stage Brecht’s controversial play Galileo. He quickly lets himself be co-opted by the church’s orthodoxy (after all, he says to Daniel, “Institutions live longer than individuals”), and rises through the hierarchy. His position gives him an opportunity to travel, and during his travels he manages to see the plays that are still in his blood and falls victim to the sins of the flesh. Just as we learn more about Richard’s failings, and are perhaps ready to dismiss him as yet another hypocritical coward and fraud, Arcand allows him a speech about the value of faith that makes us aware that a lifetime of ministry to the poor, the lonely, the sick, the desperate, and the mad is not to be discounted simply because it’s flawed. Richard is in a terrible position: his faith is genuine, his needs are imperative, he hates being a hypocrite, and he’s too afraid to abandon the only way of making a living he’s ever known to search for a more honest life.

Daniel’s second “Mary” is the beautiful Constance (Johanne-Marie Tremblay). She’s the fallen “woman of the city” who in the New Testament washes Christ’s feet and repents of her sinful life. Daniel saves Constance from a “career” that sees the image of her body sold to ad agencies as a come-on for the latest incarnation of hedonism, and herself surrendered as a plaything for men with Rolexes and BMWs. Constance is aptly named. As in the Biblical version, the support of the women in Daniel’s personal passion is more unflinching than that of the men. There is no record of Christ’s female supporters denying him because they feared the authorities.

The two other actors Daniel recruits are René (mentioned earlier) and Martin (Rémy Girard). Martin was paying the rent by dubbing French dialogue onto foreign pornographic films destined for the Quebec market. Once again, director Arcand is making no attempt to shock or be irreverent. Although Jesus of Montreal contains some strong language and very brief nudity, none of it should be any more shocking than Jesus’ association with publicans and sinners. Of course, some people will be shocked or disturbed. A film about Jesus with a “R” rating will seem blasphemous. Christ’s own apostles were concerned by some of the company He kept. But what would be the value of a ministry that turned its back on the outcasts? What would be the value of a cinema that insisted that sacred and the profane could never coexist?

Jesus of Montreal even has its own devil to tempt Daniel: a slick corporate lawyer (Yves Jacques) who from an office on the top floor of the highest building in Montreal offers Daniel book deals, high-profile charity work, and talk show slots. It’s a marvellous role, subtler and smarmier than Al Pacino’s scene-chewing corporate Beelzebub in The Devil’s Advocate.

With the possible exception of the priest who hires him, Daniel’s immersion in the role of Jesus is a positive influence on the lives of everyone around him. Spectators at the Passion Play are profoundly moved. Predictably, however, Daniel’s new version of the Passion Play, although a success with the public, runs afoul of higher church authorities. Daniel’s Jesus is akin to the “activist” Christ of liberation theology, which focuses on salvation through freedom from social, political, and economic oppression. Liberation theologians have had a difficult time of it with Vatican authorities in Rome. Theirs (and Daniel’s) is sometimes as much the Christ who drove the money changers out of the temple as it is He who said to turn the other cheek and return hurt with forgiveness.

As I mentioned earlier, through the course of Arcand’s film Daniel’s identity becomes indistinguishable from the role he’s playing. Bluteau and Arcard together bear convincing witness to Jesus’ strengths as companion, teacher, and challenger to the status quo. Daniel shoulders a weight impossible to bear. He does not compromise. He will pay with his own life and, in the end, achieve a strange kind of resurrection. True to form, two of Jesus of Montreal’s finest tableaux take place in the unlikely setting of a Montreal subway platform. One is a Pietà, the other two musicians singing the Stabat Mater of Giovanni Pergolesi: “When my body dies, ensure my soul will not be refused the glory of paradise….”

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

When it came time to take a second look at Jesus of Montreal, I realized that it was the only one of Denys Arcand’s films that I had seen over the years. A sad state of affairs, given that Arcand is one of Quebec’s and Canada’s most successful director-screenwriters. Fortunately, iTunes currently offers several of Arcand’s films for either rental or purchase (oddly omitting one of the best-received, The Decline of the American Empire), and I was able to watch them all.

Not, I can assure, an onerous task. Denys Arcand is a fine storyteller, both visually and through his writing, and over the years his casting has been flawless. In every one of his films, there are characters with whom you want to spend time, and who are worth your time. There is also enough variety in the kinds of stories Arcand tells to ensure his vision remains fresh. Réjeanne Padovani(1973) is an unblinking portrait of power & political corruption that plays out like the Quebecois equivalent of Francesco Rosi’s Hands over the City (1963). Gina (1975) is half National Film Board documentary on Quebec’s textile industry, and half grindhouse cinema featuring a stripper, mobsters, and sociopaths on skidoos (and, admittedly, one of the most boring games of pool in the history of the movies). Stardom (2000) is the second of Arcand’s English-language films, and was unfairly maligned for being a too-obvious satire on celebrity culture when the film’s real focus is on its central character’s struggle to find an identity not coopted by lovers, husbands, and managers. The Barbarian Invasions (2003) proves that some relationships only have a future if they’re walked away from in the present; forgiveness can be a long time coming, but comes nonetheless. Days of Darkness (2007) is also about leaving things behind, before they suck out your soul. An Eye for Beauty (2014) had something to say about infidelity, architecture and, maybe, early-onset Alzheimer’s, but I’m not sure what. The Fall of the American Empire(2018) is a kind of fairy tale, starry-eyed wish fulfilment a long way away from Réjeanne Padovani’s brutal realism.

How does Jesus of Montreal stand up to all of Arcand’s other work? I’d say it’s the best feature film he’s made to date. It’s a close call, neck-in-neck with The Barbarian Invasions. His blending of the story of Christ with what happens to a small group of actors staging an original Passion Play on Montreal’s Mount Royal is flawless and profoundly moving. I’m on my third or fourth read-through of the New Testament, and nothing in Jesus of Montreal reads false to the story of a young man standing up for his principles in a hostile environment. The film’s occasional irreverence (disciples are working on beer commercials & porn dubbing when called to service; a Hamlet monologue finds its way into the Gospels) is a strength rather than a weakness. Irreverence and relevance often go hand in hand, and our greatest playwrights showed that humour can be a tool to heighten tragedy. Some may prefer Mel Gibson’s blood-soaked literalism in The Passion of the Christ (2004); I’d prefer a double bill of Jesus Christ, Superstar and Jesus of Montreal, with Monty Python’s sketch of the Pope & Michelangelo for the intermission. I only hope I’m still around when someone new manages to once again magically weave the sacred and the profane.

I did find one theme in several of Arcand’s films that troubled me. Every time we see a public hospital, and they turn up in three or four of films above, the overcrowding is appalling and no one seems to give a damn. As someone who owes his life to the quality of public health care in Canada, I take exception to what amounts to anti-health care propaganda in Arcand’s work. Given the quality of provincial services in Quebec in general, I’m not sure where the director’s rancor comes from. That level of naked cynicism seems like a personal vendetta. Arcand seems to prefer the American health system, where money talks. In The Barbarian Invasions, the wealthy, self-made son is able to buy the kind of health care for his dying father that no one else is able to get or willing to offer. In Jesus of Montreal, the young actor who plays Christ is killed by the indifference and incompetence of the public hospital to which he’s first brought.

It’s an odd point of view from a man who was once considered on the left of the political spectrum. The same applies to Arcand’s repeated union bashing. Just because union corruption exists doesn’t mean you get to portray all union workers as lazy slackers on the take. The same goes for government bureaucrats. In Arcand’s world, they’re all drones in a faceless, soulless vacuum. Conscientious government workers are rarer than unicorns. This contempt for the state strikes me as hypocritical coming as it does from an artist who has worked extensively with the National Film Board of Canada and whose ability to continue making films in Canada is in part guaranteed by generous financial support from both provincial & federal levels of government. I have nothing against mocking “the System” per se—it has its fair share of failings—but at some point one should express some gratitude for its successes. Perhaps Denys Arcand could spend more time with Frederick Wiseman’s documentaries, which can be both devastating and generous.

I haven’t yet had a chance to read an in-depth study of Denys Arcand’s life & work—is it possible he’s been spending a lot of time with Ayn Rand novels and on Libertarian websites? His denigration of the public service would play rather well with Donald Trump’s fan base. Or Stephen Harper’s. Or Jason Kenney’s. I’m hoping that’s not the effect he was going for. We don’t need more of our best & brightest jumping on the Neo-Con bandwagon.

A footnote: Check out Jay Scott’s fine review of Jesus of Montreal in the posthumous anthology Great Scott! Scott was one of Canada’s most respected film critics. Of Arcand’s film he wrote: “This movie sends the shopper home with a secularized but nonetheless sacred sense of life: it fills the eyes with rapture, the mind with energy and the heart with love.”

Available on YouTube? Yes, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hiBBl4bNINM

Also available for rental or purchase through iTunes