Those who have crossed

With direct eyes, to death’s other Kingdom

Remember us—if at all—not as lost

Violent souls, but only

As the hollow men

The stuffed men.

–T.S. Eliot, The Hollow Men

“It took a moment to comprehend that something [the September 11th terrorist attack on New York and Washington] was being transmitted on a medium that so often makes so much of so little.”

–Scott Feschuk, National Post, Sept. 12th, 2001

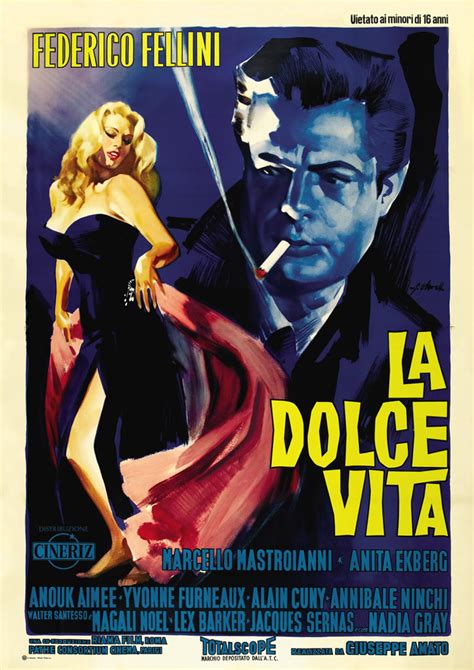

Even many of us who are movie buffs have only a passing familiarity with the early works of Frederico Fellini. The later work, with its hallucinatory conjurings, is what has imprinted itself indelibly on our memories.

There was another Fellini, however. This other Fellini was a student of Italian neo-realism, a man interested in capturing in gritty black and white the essence of post-war, industrializing Italy. It was not an Italy he particularly liked.

In his early years, in the 1940s, Frederico Fellini actually worked closely with the great neo-realist director Roberto Rossellini on several of his finest films. This young Fellini was fascinated and repulsed by the new Italian society, which was building ugly sterile housing complexes instead of cathedrals; which worshipped the cult of celebrity with the fervor of Moses’s followers before the Golden Calf; and which replaced the grand tradition of artistic patronage of the Medicis with that of a new jet-set aristocracy that played at art and literature, choosing poets and painters like bottles of wine to be discarded after the next feast. Even neo-realism itself, instead of ushering in a new era of truth in cinema, was supplanted by the new age of media and the triumph of style over substance, of escapism over analysis.

In the year 1960 Fellini was looking both backwards and forwards. He was still drawing on the visual authenticity and documentary stylings of neo-realism, but was shifting towards the phantasmagoria of 8 ½ (1963) and Satyricon (1969). The opening sequence of the masterpiece he made in 1960, La dolce vita (“The Sweet Life”), has the kind of visual impact we associate with the later films: the opening sequence consists of aerial photography of a gilded statue of a preaching Christ suspended beneath a helicopter, flown over Rome’s ancient and modern cityscapes. Other set-pieces are as startling: the fraud and media circus (a phenomenon which Fellini understood perfectly before anyone else had even thought of a name for it) of a “miraculous” appearance of the Virgin Mary to two conniving children; fisherman hauling a monstrous dead manta ray onto a beach (to the shocked fascination of hung-over party-goers); Anita Ekberg wading through the Trevi fountain in a scene that registers on masculine radar as indelibly as Marilyn Monroe standing over that subway vent in The Seven Year Itch. La dolce vita has a three-hour running time, and Fellini wastes none of it.

Fellini perhaps has the unique distinction of contributing not just one but two words to the English language. “Felliniesque” is self-explanatory, but how many people know that the paparazzi who were vilified after Princess Diana’s death were baptized by La Dolce Vita? One of the secondary characters in the film is a press photographer hell-bent on capturing every squalid detail of every public humiliation, infidelity, suicide, and murder. His name? Paparazzo.

The elements of La Dolce Vita which I’ve described thus far make it a fascinating movie, not necessarily a great one. But it is a great film, and that distinction comes from the story it tells of the imploding life of its central character—a journalist named Marcello, played brilliantly by Marcello Mastroianni.

La dolce vita is an unspeakably sad film. It’s one of the few that has a sense of tragedy as poignant as that of any of the great plays. Marcello’s story is the classic one of a man with genuine talent and tremendous charisma whose life begins to drift unstoppably. Capable of writing a great novel, he lets his energies be sapped by the so-called easy money of tabloid journalism. Capable of inspiring passionate love, he squanders that gift in meaningless beddings of chorus girls, jaded society women, starlets and poseurs.

Often in tragedy the fatal drift is towards violence and more violence. In La dolce vita the tragedy is a relentless hollowing out. The handsome façade is left more or less intact, but the eyes that mirror the soul go vacant. Marcello is like a man who sets out to sea on one of those little inflatable mattresses, drink in hand, and who lets the waves carry him and the sun burn him until he is so far from any shore that any action seems pointless. There is no hope of rescue.

There are moments in La dolce vita where Marcello’s life could turn around. Each moment is lost. Marcello’s father comes to Rome for an unexpected visit. Marcello takes him out for a night on the town, and dad starts to relive some of the machismo of his youth. Father and son begin their first real conversation since Marcello left home. Sure, it’s based on mutual womanizing and sexist posturing, but at least they’re talking. Then the father suffers a minor stroke in the bed of one of Marcello’s ex-girlfriends, climbs into a taxi a much older man than when the night began, and leaves Marcello with everything unsaid.

Marcello’s fiancée, Emma (Magali Noel), attempts suicide to shock him out of his serial infidelities. The attempt fails. Their love-hate relationship is painfully real, the cinematic equivalent of some of Picasso’s most misogynistic work.

Anita Ekberg’s role extends the movie’s sadness into real life. Her fifteen minutes onscreen is one of the most glorious, ephemeral celebrations of sensuality in the history of cinema. Marcello pines after her like a puppy. His desire for her is almost innocent in its unadorned eagerness. But that fifteen minutes is all there is. For Marcello and for Anita Ekberg. She virtually disappeared from the screen, surfacing in inconsequential pictures like Fangs of the Living Dead, Gold of the Amazon Women, and The Killer Nun.

La dolce vita’s most horrific failure to communicate involves the one man Marcello looks up to as a mentor and a friend. Steiner (Alain Cuny) is the ultimate aesthete. A brilliant, multi-talented, powerful man with a model family and a chic salon. Steiner’s terrible end is Marcello’s coup de grace. If before he has let himself drift into decadence, after Steiner’s death he throws himself into meaninglessness with a vengeance.

La dolce vita ends with a monster and an angel. I’ve already mentioned the monster: the dead ray with the staring eye that’s really what’s left of Marcello. The angel is an innocent young woman Marcello had once met on a beach where he had been, futilely, trying to work on his novel. She waves joyfully to him from a distance on another beach to where he has staggered after an all-night orgy. His red-rimmed eyes fail to recognize her. Innocence and beauty no longer register. There can be no greater loss.

MINI-SELDOM SCENE

Dead Man, directed by Jim Jarmusch, starring Johnny Depp, Gary Farmer, Lance Hendrickson.

Better Title: Lots and Lots of Dead Men

Message: The Old West really, really sucked

Real Reason to Rent: Neil Young’s soundtrack

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

“Masterpiece” is not a word I use often in my reviews, for fear of watering down its impact to something approaching “really good.” In the case of La dolce vita, however, what other word can one use? This film represents Fellini at the height of his power as a filmmaker, capturing the anomie and decadence of a segment of modern society that continues to resonate through the third decade of the 21st century. The rich have only gotten richer, celebrity culture more unhinged, and spiritual values increasingly warped, vitiated, or confused. I don’t know if there’s a brilliant cinematic adaptation of Albert Camus’ The Stranger out there somewhere, but I’d suggest that La dolce vita captures that existentialist cri de coeur as well as any film ever made. Added to La dolce vita’s thematic power, there’s the magnificent lighting and black & white cinematography of Otello Marteli, the signature music of Nino Rota, and the flawless production design of Piero Gherardi.

As counterpoints to the sacrilegious scenes of helicoptered Christs, publicity-hungry children chasing after the Madonna, predatory paparazzi. and half-hearted orgies, Fellini’s film also has, astonishingly, moments of almost sacred stillness—Anita Ekberg seated in the light of a casement window on the re-created curved staircase inside the shell of St Peter’s dome, Ekberg and Mastroianni in the Trevi Fountain when the water shuts down, the young girl smiling at Marcello from across the strand. This is Fellini in perfect equilibrium between his earlier neo-realist-influenced films and his later grotesqueries. The latter show up in La dolce vita in the bizarrely mismatched couples one sees in nightclubs and at parties, and in the monstrous manta ray that’s pulled up onto the beach at the film’s end.

While it might have been easy to dismiss the decadence as merely the sybaritic excesses of the uber-rich, the screenplay adds a layer of genuine tragedy with Steiner’s umimaginable murder of his family and his subsequent suicide. Here is the true cost to be paid for a lifestyle that feeds the appetites but not the soul. It’s also a reminder that those who built and ran the Nazi concentration camps had their own families, read Goethe and Schiller, and admired Beethoven, Wagner, and Bruckner. As one character in La dolce vita says, “Peace frightens me because hell is behind it.”

When one reads of the struggles Fellini had with producers to try and piece together the funding for his films, the descriptions of his improvisatory approach to screenwriting, the shambling search for actors, and the inevitable cost overruns, it seems a miracle that Fellini’s great films were completed at all.

There is one small detail in the famous Trevi fountain scene that I’d never noticed before and that, for me, perfectly captures the essence of Fellini’s art. In the closing shot of one of this most iconic of film scenes, the camera pulls away from the Sylvia and Marcello and, in the foreground, we see, staring at them in bewilderment, a white-clad, middle-aged bicycle deliveryman holding a pizza box above his head. Fellini will never take himself so seriously that, whatever else may be going on, he’ll forget that there’s always a pizza delivery guy out there to bring you down off your high horse.

Other things that stayed with me from this viewing: the ugliness of the new residential high-rises on the outskirts of Rome, the phantasmagoria of the lighting towers that dominate the frenzy of the children’s visitation scene, the Pied Piper party in the abandoned mansion, Alain Dijon’s grooving Beat-era satyr, the glimpse at Giorgio Morandi’s paintings, and the risibly fake folk singing session.

From the La dolce vita chapter of John Baxter’s Fellini biography:

MGM boasted: ‘1960 is the Year of Ben Hur’, but 1960, in Europe at least, was really the year of La dolce vita. It thrust every other film into the shade. Fellini became at the same time a household name and a public enemy. ‘Everywhere in Italy,’ he said, shaken, ‘La dolce vita was like a bomb.’

———-

[on a typical Fellini set, as described by American critic Stanley Kaufmann at the time of Il bidone] ‘The crowd of waiting extras, playing cards, chatting drinking wine, staring into space, is a gallery of aces chosen with a Daumier eye. In the midst of the early morning hubbub, as carpenters hammer, electricians yell, lights glare on and off, trucks rumble, Fellini calls for a chair and a small table. With chaos eddying around him, the huge man hunches over a typewriter, rewriting the pages that he plans to shoot today…He rehearses and shoots a short scene over and over. One can see that he is not only refining the performances and camera movement, he is also refining his ideas of what it is that he wants from a scene.’

——-

These were the anni caldi, the hot years. The centrist Christian Democrats were under siege from the Communists, and Italian society bubbled yeastily in the burgeoning economy. To represent this Italy, amoral and greedy, [Fellini] needed a cynical middle-aged version of Moraldo [a character in a projected screenplay], ‘already a little hardened, already at the edge of shipwreck’—like Fellini himself.

——–

Every episode in the film was suggested by a Roman scandal of the last ten years,’ wrote Time magazine, ‘and Fellini has somehow persuaded hundreds of Roman whores, faggots, screen queens, press agents, newsmen, artists, lawyers and even some authentic aristocrats to play themselves-or revolting caricatures of themselves.’

Rome buzzed with such scandals in 1958….Life in the Rome of 1958 was one long manoeuvre. Gossip, the principal currency, was traded on via Veneto, the reef where the bottom-feeders of the Roman night browsed. At the outdoor tables of the Café de Paris, Rosati, the Strega-Zeppa and (a favourite of film people) the Doney…journalist and photographers swapped notes and reported the news, or created it. Any fast-breaking story could be delivered by Vespa to scandal sheets like Lo specchio and L’espresso, close by.

…Magazines offered only 3,000 lire for a straight shot, whereas famous pictures like that of an enraged Walter Chiari chasing [photographer Tazio] Secchiaroli or the series shot on 15 August 1958 of a white-faced and furious Anthony Steel storming towards him were worth 200,000 lire. If no celebrity fist-fights occurred spontaneously, these men engineered them….Flattered by Fellini’s interest, the photographers described how they tracked, stalked and goaded their victims. ‘We work like commandos,’ Croscenko explained. ‘You come, you shoot everyone, you run away.’ And Secchiaroli boasted: ‘I’m like a paratrooper. I don’t take pictures—I make war.’….

Fellini didn’t have to look far beyond tabloid headlines for the plot of La dolce vita. Pictures of a Christ statue being carried across Rome by helicopter had appeared in most papers on 1 May 1950. In June 1958, Secchiaroli grabbed front pages with pictures of two teenage girls from Terni who claimed to have seen the Madonna. Fellini coopted both incidents….The most shrill of all headlines, however, were provided by the Montesi Case. In April 1953 the body of twenty-one-year-old Wilma Montesi was found on the beach near Ostia. She wore no shoes, stockings or underwear, and it was rumoured she’d overdosed at an orgy on the nearby Capocotta estate and been dumped on the beach, to drown in the incoming tide….The court acquitted everyone [accused in the case], but memories were still fresh when Fellini started La dolce vita.

——-

…’we must make a film like a Picasso sculpture; break the story into pieces, then put it back together according to our whim.’ [Fellini]

——-

Fellini saw women’s fashions and their appearance in magazines like Oggi and Europeo as symptomatic of Rome’s decadence.

——-

In November 1958 Ekberg, with Ingrid Bergman and the rest of Rome’s glitterati, attended the party at Rugantino’s for American millionaire P.H. Vanderbilt, where Turkish dancer Aichi Nana performed an impromptu strip, ending in a writhing climax on coats laid over the tiled floor. Inspired by the headline ‘La Turca Nuda’ and Secchiatroli’s images of Nana, naked but for black panties, sprawled at the feet of her chic, expressionless audience in the glare of the flashguns, Fellini added the strip-tease that became La dolce vita’s most controversial scene.

——-

[A major media campaign was launched to find the girl who would play the innocent Paola on the beach at the end of the film, but Fellini wound up choosing the fourteen-year-old daughter of a man who’d invited him to dinner at his home.]

——-

In 1959 Fellini paid a visit to the Cinecittà set of Ben-Hur, where he met novelist, classical scholar and screenwriter Gore Vidal….Engaging as he found Vidal, Fellini was more impressed by the CinemaScope camera. Twentieth-Century Fox had pioneered the new screen size six years before, but it main use until then had been on epics and westerns. Fellini saw that the narrow viewpoint of Marcello’s story could be expanded if he discarded the standard 1.33:1 ratio for the 2.55:1 of CinemaScope….With ‘Scope, Fellini was able to embed the incidents of the film in its larger and more important subject, Rome itself. He told Otello Martelli to abandon is wide-angle lenses and use mainly the longer 75mm, 100mm and occasionally 50mm lenses normally reserved for close-ups. These gave a shallow depth of field, throwing foreground and background out of focus. La dolce vita has no panoramas. The characters seem to carry their own private Romes around with them….Though the film used more than 800 performers, eighty-six of them with speaking roles, the overall impression is of lone figures in empty landscapes. ‘Fellini said that we should have the air of castaways on a raft,’ said Mastroianni, ‘going where they were driven by any puff of wind, totally abandoned.’

——-

May roles were still uncast when the film started shooting. The small ones were easy, Fellini filling them, as usual, on impulse.

——-

‘A Fellini production is a little like the court of Louis XIV at Versailles. A favourite could fall into disgrace. This happened to me. There was a period of crisis, of misunderstandings.’ [Dominique Delouche]

——–

[Don Peppino Amato’s] Cineriz company would distribute the film. Fellini’s fee would be the equivalent of $50,000, at the low end of the Hollywood scale, plus a share of the profits. The terms were not particularly advantageous to Fellini, but by then he thought only of starting work. [To Fellini’s credit, it was often more about the work than the money.]

——–

[Ekberg] breezed through the sequence at the Caracalla Club, Gherardi’s caricature of a Rome boîte, built against the ancient walls of the baths. In the Rome of La dolce vita everything is for sale, even the imperial past.

——–

Fellini set many scenes in or near fountains and running water, part of a motif that contrasts natural phenomena—water, wind, rain, animals—with Rome’s sterile artificiality, and also acknowledges Fellini’s superstitious regard for his astrological sign, Aquarius. Gherardi turned the Acque Albule, a suphur spa at Bagni di Tivoli outside Rome, into the Kit Kat Club, which Marcello visits with his father, while its exterior became a poolside terrace at Maddalena’s mansion. The miracle scenes were also shot near by, with Fellini’s psychic adviser of the time, Marianna Leibl, playing a small role as the woman who befriends Emma.

Re-creating the tritons and mermaids of Niccolò Salvi’s intricate Fontana di Trevi was, however, beyond even Gherardi’s powers, so Fellini took it over for Sylvia’s famous wade….The original paddle had taken place in August, with the actress wearing a modest belted cotton frock, hair demurely pinned up. This time [March] Fellini put her in a low-cut evening gown and set her hair free. Since the waters were icy, Ekberg’s exposed shoulders and arms were rubbed down with alcohol after each of the fiteen takes to help circulation. Mastroianni took his alcohol more directly.

———

Unable to get the shots he needed [on the real via Veneto], Fellini told Gherardi to re-create at Cinecittà the block of the Veneto in front of the Café de Paris. When [[producer] Amato balked at the cost, he agreed to give up his profit participation.

——–

When he finished shooting on 17 August, Fellini had exposed 92,00 metres of film—fifty-six hours—which would be cut to less than three. Mastroianni, who’s in every sequence, remained enthusiastic to the end. ‘it was an exceptional experience, marvellous; almost six months of joyful labour. One didn’t really have the impression of making a film. We almost lived that “soft life”.’

——–

Rota’s music is among the most distinctive of all film scores, mostly for its use of the Cordovox, an electric organ whose compressed, droning tone, combining harmonium, Hammond organ and a wooden street organ, became a Fellini trademark.

——

Any [Catholic] priest who reviewed the film favourably was disciplined, demoted or transferred to a new parish. Il quotidiano, the newspaper of Catholic Action, initially printed a good review, then recanted, deciding it was blasphemous, pornographic, bestial and un-Italian….The Centro Cattolico Cinematografico, the Church’s mouthpiece on movies, rated it E (for ‘Escluso’), damning any Catholic who saw it….Within twenty-four hours of the opening Fellini received 400 telegrams, mostly accusing him of treason, atheism and Communism…Ironically, Communist critics who’d harried him for abandoning Neorealism found themselves forced to praise La dolce vita in the name of the party line. Faced with such solidarity on the left, some political journalists charged that Fellini had hastened the long-feared apertura della sinistra, the ‘opening to the left’ which would admit Communists to the government. There were calls to withdraw his passport….For Fellini, the assaults were painfully personal. ‘In Rimini, my mother is still known as the mother of the man who made La dolce vita.’

——–

Neither Church nor state could, however, stem La dolce vita’s enormous success. Two big Roman cinemas ran four packed shows a day for months. Despite the extraordinary cost of 1,000 lire a seat, cars were parked three deep outside. So huge were the queues in both Rome and Milan that people drove hundreds of kilometres out of town to see it. Within three months it grossed $1.5 million, smashing records set by The Ten Commandments and Gone with the Wind. By the time it opened in New York City in April 1961, the film had made $10 million.

From Tullio Kezich’s Fellini biography:

After a series of delays, because he crew can shoot on via Veneto only late at night and with a plethora of regulations, the producer agrees to reconstruct a section of the notorious street in Studio 5 at Cinecittà. At a cocktail party on June 6, Rizzoli expresses concern over the ballooning costs. The sidewalk in front of Café de Paris is a perfect replica of the original, except for the fact that it’s not set on a slope. Federico insists to everyone that cinema doesn’t have to imitate reality but merely reinvent it, and praises Cinecittà’s via Veneto as better and more real than the original. At a certain point later on, he’ll decide that he always wants to reproduce everything and stops shooting on location.

——-

Because of its daily surprises, unexpected location changes, and the constant shifting of characters and scenes, production on La dolce vita will be remembered as a unique experience by those who were there. It was something of a long holiday for Federico….

——–

The final edit of La dolce vita runs three hours. Like many great movies—Intolerance, Greed, and Ivan the Terrible—the length itself is already an event. It isn’t long because of any initial decision to make an exceptionally long movie, but because of the ongoing, progressive development of themes and characters over the course of five feverish months of filming. Fellini’s initial concept was to show a series of anecdotes about an archetypal figure of society, the journalist. He ended up painting a grand portrait of the whole world. Some critics will foreshadow a future chapter in Fellini’s filmography by labeling this picture the Satyricon of the twentieth century….the film is a tragic allegory of the desolation lurking behind the façade of a perpetual carnival.

——–

….within the parameters of a complacent, macabre dance in a doomed world, …the movie actually depicts a lucid self-examination. Analyzed scene by scene, it certainly does appear to be a tale of failure—but how then to explain La dolce vita’s inherent serenity? How its broad meaning contrasts with the dark, bitter, and frightening atmosphere of the movie’s individual scenes? The leviathan is also a fish. Many of our fears are born of illusion, rhetoric, and sentimentality. La dolce vita takes it all on, deconstructs and demystifies it. Fellini has reached a complete maturity, and he’s inured to the temptation of satire, caricature, or desperation….the movie is arid, virile, and absent of chicanery. The director seems to be saying: Let’s try to see things as they are, and the clouds will disappear from the horizon.

The movie’s poetry comes out of its respect for its characters, even the most notorious and undeserving ones.

Also worthwhile checking out—Roger Ebert’s review of La dolce vita in the first volume of his The Great Movies tetralogy (available online at Rogerebert.com).

Available on YouTube? No, but available for rental on YouTube