“Sickened by virtue he rebelled and cried

For all things horrible to be his bride

For through the hot red tides of sin move such

Fish as lose radiance at virtue’s touch.”

–from Mervyn Peake’s Selected Poems

Rampant. An interesting word, isn’t it? Applied to something unpleasant, it means spreading in an uncontrolled way. Rampant corruption. In another context, it means violent or extravagant in action or opinion. Rampant snobs. For plants, the implication is one of rank and luxuriant growth. Rampant nasturtiums. In heraldry, it refers to a picture of an animal standing on its left hind foot with its forepaws in the air, exhibiting fierceness. Lion rampant. Architects use the word to describe arches or vaults having abutments on different levels. There’s even a now obsolete use of the word as a synonym for lustful and vicious. “Lest his body grow rampant…the church orders him to fast.” All these roots have their origin in the Old French verb ramper, which meant “to creep, to crawl.”

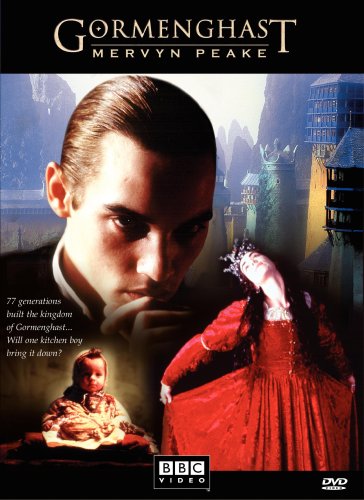

Rampant digression? Hardly. For this month’s review I’d like to suggest a movie, and the books upon which it was based, that bring to vivid life each and every nuance of meaning catalogued above. One can think of the four-hour BBC adaptation of Mervyn Peake’s monumental Gormenghast novels as Masterpiece Theatre on steroids. An act of bravado, of sheer cinematic hubris, that may have been impossible before our age of digital effects wizardry. The three novels (Titus Groan, Gormenghast, Titus Alone) that Peake wrote before illness forced him to abandon his work rank among the greatest works of allegory since the Arthurian stories of the Middle Ages. To my mind, Gormenghast is the only modern work of fantasy to rank with J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. It’s as if an alchemist had distilled all of the darkness out of Middle Earth and infused it into the stones of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, causing every gargoyle and imp and serpent and saint and prophet and buttress and pillar to twitch and shudder and come alive with malignant intent. Imagine something borne of Hieronymus Bosch’s eye, Charles Dickens’ pen, Shakespeare’s stagecraft, and Franz Kafka’s nightmares.

The city-state of Gormenghast is a vast excrescence of stone. There are 638 rooms on the first floor of the east wing, 503 on the second, 700 on the third. The clock above the main square could shelter a battalion. Trees bigger than California redwoods are rooted in the palace walls. I’ll tell you more about Gormenghast and its inhabitants in a moment, but first I’d like to indulge in a long quote from the first of Peake’s books. It’s the reader’s first look at Swelter, the monstrous chef of Gormenghast’s Great Kitchen. I didn’t choose this passage because it’s exceptional; believe it or not, it’s actually typical of almost every one of the story’s 1300 pages. Mervyn Peake was a superb artist as well as a master storyteller. No surprise that movie directors haven’t been lining up to tackle this modest little project:

“The long beams of sunlight, which were reflected from the moist walls in a shimmering haze, had pranked the chef’s body with blotches of ghost-light. The effect from below was that of a dappled volume of warm vague whiteness and of a grey that dissolved into swamps of midnight—of a volume that towered and dissolved among the rafters. As occasion merited he supported himself against the stone pillar at his side and as he did so the patches of light shifted across the degraded whiteness of the stretched uniform he wore….One of the blotches of reflected sunlight swayed to and fro across the paunch. This particular pool of light moving in a mesmeric manner backwards and forwards picked out from time to time a long red island of spilt wine…[the] ungarnished sign of Swelter’s debauche….”

Debauche, indeed. For all the visual detail lavished upon him, Head Cook Swelter is the merest carbuncle upon the monolithic body of Gormenghast itself. Gormenghast crushes the vitality of its denizens beneath centuries of tradition and ceremony. Spontaneity is obliterated. Nothing must ever happen which has not been sanctified by precedent. No one must ever happen whom precedent has not slotted into his or her predestined station in life. What was must be what is, and will always be. “What is Law?—That is what always has been. Law is destiny. Obedience is tradition.” The peasants stay peasants and the stone scrubbers stay stone scrubbers and the dukes stay dukes. Amen. The past encrusts itself upon everyone and everything in Gormenghast like a creeping (rampant?) plague of barnacles that threatens to leave nothing but grotesque tableaux vivants.

Gormenghast is France before Robespierre, Russia before the Revolution, China before Mao, the Old World before World War I ripped a hole across its belly. For the film, the BBC set designers have succeeded in creating an effective amalgam of oriental and occidental influences. Call it Tibetan Gothic. About the only thing missing is the ductwork from Terry Gilliam’s Brazil—the only other modern fantasy film that’s playing in the same twisted league.

History and literature tell us that for every self-satisfied Othello there’s an Iago waiting in the wings to take him down. For every Medici, a Borgia. For every Czar, a Lenin.

And for every Groan, a Steerpike. On the level of acting, Gormenghast belongs to Jonathan Rhys-Meyers as Steerpike, the kitchen boy whose hate-fueled ambition will burn his world to ash. The relish with which Rhys-Meyers manipulates the stupidity, vanity, ambition, and greed of his so-called “betters” reminded me of a young Laurence Olivier. To shamelessly switch metaphors, Gormenghast is the overstuffed sofa…and Steerpike is the knife.

This is not a fantasy for young children. Death stalks the stones. There’s blood at midnight. The one overwhelming impression I was left with when I read Titus Groan back in high school was of darkness upon darkness. No film could ever layer it as deeply or skillfully as did Mervyn Peake, but director Andy Wilson and screenwriter Malcolm McKay do not disappoint.

Although even a four-hour running time meant the loss of several minor characters (Mr. Rottcodd, Sourdust) and even some major ones (Lord Sepulchrave), the company that’s left is still unwholesomely splendid. Or is that splendidly unwholesome? Check’em out. Nannie Slagg, the ancient, perpetually tottering nursemaid. Gormenghast’s own eminence grise, Mr. Flay (Christopher Lee in his best, albeit monosyllabic, role in ages—“NOT of the stones! Bad, Lordship, bad!”). The aforementioned Swelter (Richard Griffiths). Dr. Prunequallor (John Sessions) and his man-struck spinster sister, Miss Irma (Fiona Shaw). The demented 76thEarl of Groan (Ian Richardson), and his flint-hearted wife Lady Gertrude (Celia Imrie). The helium sisters, Lady Clarice and Lady Cora (Zoe Wanamaker and Lynsey Baxter). Secretary Barquentine, hobbling about like a stunted Ahab and forever damning poets for their insolent unpredictability. Lovely, lovelorn Fuschia Groan Neve MacIntosh). And, just in case something was lacking, a cameo appearance by Spike Milligan as a narcoleptic headmaster.

Did I mention Cameron Powrie and Andrew Robinson as the adolescent and adult Titus Groan? No? Too bad. That’s what you get for being normal in a place like Gormenghast.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels are a stunning literary achievement, with some of the finest descriptive writing I’ve ever come across. I’ve often thought about reading the whole of the first volume aloud just to immerse myself in its High Baroque style. Titus Groan is over 500 pages long, and you could almost count the plot points on one hand. All the rest is atmosphere and character description. Most surprising of all, perhaps, in this brilliant work of fantasy, there’s nothing supernatural. Instead, there’s the great stone mass of Gormenghast castle itself, and its extraordinary inhabitants. The vision is truly Shakespearean, but the tragedy is more Richard III than Macbeth.

The BBC’s four-part attempt to film the first two books of the Gormenghast trilogy was praiseworthy. It’s a daunting challenge to try and condense a thousand pages of inimitable prose into four hours of television. The cast was superb, particularly a young Jonathan Rhys Meyers in the central role of Steerpike. Also memorable were Christopher Lee as the sepulchral Flay, Ian Richardson as Lord Groan, Fiona Shaw as Irma Prunesquallor, Celia Imrie as Lady Gertrude, Warren Mitchell as Barquentine, John Sessions as Dr. Prunesquallor, Stephen Fry as Professor Belgrove, and Zoë Wannamaker & Lynsey Baxter as the sisters Clarice & Cora Groan. Seeing these characters brought so vividly to the screen felt like an affirmation of Mervyn Peake’s astonishing artistry. It doesn’t hurt that Peake himself drew vivid sketches of all his major characters.

Far less successful than the casting of Gormenghast was the production design for the sets themselves. This is not the Gormenghast whose great, crumbling grey stones become a breeding ground for petty treacheries, venal eccentricities, and lethal resentments. The Gormenghast we see here seems closer to an Arthurian Camelot than to Dickens’ Bleak House or Franz Kafka’s Castle. It’s Gormenghast as it might have looked when it was first built, not as it was in the End Days. It may have been that the director, the production designer, and the art director simply didn’t have the tools they needed in 2000 to translate as dense a vision as Peake’s to the screen. Or they may have been worried about compounding a grim tale with a grimmer setting. Now that we’ve seen what can be done with Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones, Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, and Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, we can only hope that someone, somewhere is thinking that the Gormenghast trilogy has not gotten the full treatment it deserves.

I’m not holding my breath, however. Mervyn Peake’s work has had a hard time finding the full recognition it deserves. The debilitating illness that robbed him of the ability to paint and write during the final years of his short life (he was 57 when he died) left his wife and children to defend his legacy. There was even a time when the trilogy was virtually out of print. Even now, in the third decade of the 21st century, a new, deluxe edition—along the lines of the Rings illustrated by Alan Lee—is long overdue.

If I haven’t yet convinced you that Titus Groan’s story deserves a place on your bedside reading list, perhaps a few excerpts from Titus Groan will help make my case. They are taken from the 1968 Ballantine Books paperback edition:

“Cat Room,” said Flay again, ruminatively, and turned the iron doorknob. He opened the door slowly and Steerpike, peering past him, found no longer any need for an explanation.

A room was filled with the late sunbeams. Steerpike stood quite still, a twinge of pleasure running through his body. He grinned. A carpet filled the floor with blue pasture. Thereon were seated in a hundred decorative attitudes, or standing immobile like carvings, or walking superbly across their sapphire setting, interweaving with each other like a living arabesque, a swarm of snow-white cats.

As Mr. Flay passed down the center of the room, Steerpike could not but notice the contrast between the dark, rambling figure with his ungainly movements and the monotonous cracking of his knees, the contrast between this and the superb elegance and silence of the white cats. They took not the slightest notice of either Mr. Flay or of himself save for the sudden cessation of their purring. When they had stood in the darkness, and before Mr. Flay had removed the bunch of keys from his pocket, Steerpike had imagined he had heard a heavy, deep throbbing, a monotonous sealike drumming of sound, and he now knew that it must have been the pullulation of the tribe.

————–

The attic, [Fuchsia’s] kingdom could be approached only through this bedchamber. The door of the spiral staircase that ascended into the darkness was immediately behind the bedstead, so that to open this door which resembled the door of a cupboard, the bed had to be pulled forward into the room.

Fuchsia never failed to return the bed to its position as a precaution against her sanctum’s being invaded. It was unnecessary, for no one saving Mrs. Slagg ever entered her bedroom and the old nurse in any case could never have maneuvered herself up the hundred or so narrow, darkened steps that gave eventually on the attic, which since the earliest days Fuchsia could remember had been for her a world undesecrate.

Through succeeding generations a portion of the lumber Gormenghast had found its way into this zone of moted half-light, this warm, breathless, timeless region where the great rafters moved across the air, clouded with moths. Where the dust was like pollen and lay softly on all things….

As Fuchsia climbed into the winding darkness her body was impregnated and made faint by a qualm as of green April. Her heart beat painfully.

This is a love that equals in its power the love of man for woman and reaches inward as deeply. It is the love of a man or of a woman for their world—for the world of their center where their lives burn genuinely and with a free flame.

—————-

Titus watched Keda’s face with his violet eyes, his grotesque little features modified by the dull light at the corner of the passage. There was the history of man in his face. A fragment from the enormous rock of mankind. A leaf from the forest of man’s passion and man’s knowledge and man’s pain. That was the ancientness of Titus.

Nannie’s head was old with lines and sunken skin, with the red rims of her eyes and the puckers of her mouth. A vacant anatomical ancientry.

Keda’s oldness was the work of fate, alchemy. An occult agedness. A transparent darkness. A broke and mysterious grove. A tragedy, a glory, a decay.

These three sere beings at the shadowy corner waited on. Nannie was sixty-nine, Keda was twenty-two, Titus was twelve days old.

—————

Swelter’s eyes meet those of his enemy, and never was there held between four globes of gristle so sinister a hell of hatred. Had the flesh, the fibers, and the bones of the Chef and those of Mr. Flay been conjured away and away down that dark corridor leaving only their four eyes suspended in midair outside the Earl’s door, then surely they must have reddened to the hue of Mars, reddened and smouldered, and at last broken into flame and circled about one another in ever-narrowing gyres and in swifter and yet swifter flight until merged into one sizzling globe of ire, they must surely have fled, the four in one, leaving a trail of blood behind them in the cold gray air of the corridor, until, screaming as they fled beneath innumerable arches and down the endless passageways of Gormenghast, they found their eyeless bodies once again, and reentrenched themselves in startled sockets.

——————–

Again her eyes peer up at the Countess, who seems to have grown tired of her hair, the edifice being left unfinished as though some fitful architect had died before the completion of a bizarre structure which no one else knew how to complete.

——————–

Drear ritual turned its wheel. The ferment of the heart, within these walls, was mocked by every length of sleeping shadow. The passions, no greater than candle flames, flickered in Time’s yawn, for Gormenghast, huge and adumbrate, outcrumbles all. The summer was heavy with a kind of soft gray-blue weight in the sky—yet not in the sky, for it was as though there were no sky, but only air, an impalpable gray-blue substance, drugged with the weight of its own heat and hue. The sun, however brilliantly the earth reflected it from sone or field or water, was never more than a rayless disc this summer—in the thick, hot air—a sick circle, unrefreshing and aloof.

From A World Away, Maeve Gilmore’s memoir of her husband, Mervyn Peake, and their children:

Unless one has a positive means of income, it is difficult to live on an island [Sark, in the Channel Islands], away from the people who can make it possible for an artist to survive.

Dawning gradually was the knowledge that the life we were leading would have to change. There was not enough money coming in, and yet looking back we lived with no extravagance. The extravagance was the life we were living.

————————–

This is the problem of the artist—to discover his language. It is a lifelong search, for when the idiom is found it has then to be developed and sharpened. But worse than no style is a mannerism—a formula for producing effects, the first of suicide.

If I am asked whether all this is not just a little ‘intense’—in other words, if it is suggested that it doesn’t really matter, I say that it matters fundamentally. For one may as well be asked, Does life matter?—Does man matter? If man matters, then the highest flights of his mind and his imagination matter. His vision matters, his sense of wonder, his vitality matters. It gives the lie to the nihilists and those who cry ‘woe’ in the streets. For art is the voice of man, naked, militant, and unashamed. [taken from the Foreword Peake wrote for the book The Drawings of Mervyn Peake)

———————-

It is hard to write of someone else’s pain dispassionately. But to watch degeneration, the slow degeneration, both mental and physical, of a brain and of a being is perhaps more painful than the sudden shock of assassination or instant death. If I had to choose the death of someone I loved, if it had to be brutal I would say let it be sudden, don’t let it linger until what you are seeing, or whom you are seeing, bears no resemblance to the being you knew.

———————

To canalize my chaos. To pour it out through the gutters of Gormenghast. To make not only tremendous stories in paint that approximate to the visual images in Gormenghast, but to create arabesques, abstracts, of thrilling colour, worlds on their own, landscapes and rooftops and skyscrapes peopled with hierophants and lords—the fantastic and the grotesque, and to use paint as though it were meat and drink. [from a letter where Peake wrote about “trying to put his ideas of writing and painting into some kind of intellectual order”]

————————

[The long narrative poem The Rhyme of the Flying Bomb] was the last book, although I have tragic notes for the beginning of a fourth Titus—the gropings of a man, wishing to write something to surpass anything he had already done; a huge vision, and nothing to allow it to manifest itself.

There was an exhibition of his drawings in the Portobello Road, to which he went, and was still able to talk moderately coherently, but there were less and less times when he could meet people. If we went out, it was usually thought that he was drunk or drugged, and offence was taken. I longed to shelter him, and I bear resentment of the intelligent ones who turned their backs on him, thinking he was insulting them. There is pain in seeing so gentle a man cold-shouldered.

Nothing was right or could be so ever again. And yet does one ever give up hoping?

——————————

From Sebastian Peake’s memoir of his father, A Child of Bliss:

He taught life painting and drawing at the Royal Academy Schools, the Central School and other institutions, but at all other times he worked from his own home. He has always been something of an unknown figure, for all his fame with his Titus books, his Glassblowers poems, his illustrations of many of the classics [Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Treasure Island, The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner, Bleak House, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde], his plays and drawings, oil paintings and talents as a teacher. This ignorance of him as a man, apart from the establishment’s bumbling ineptness in accepting him, instead of ignoring him in their gauche, “We don’t know where to place him” excuses, is due in great part to the fact that his huge outpourings took an enormous amount of the short time he had on earth. When in due course the Aladdin’s cave of his genius is opened and the coy and the uncommitted venture in, brave enough to find that they haven’t been bitten in the process, they will exclaim: “This Mervyn Peake – of course we have always known about him, always was my favourite illustrator.”

————————-

From Joanne Harris’s “Discovering the Titus Books”:

Interestingly, for a writer frequently described in terms of ‘Gothic’ and ‘fantasy’, there is no trace of the supernatural in the Titus books. There are no witches, no ghosts, no magic, no religion—but for the wholly secular ritual of Gormenghast. Nor is there any sign of the usual non-human suspects that tend to permeate fantasy fiction. To Peake, humanity itself already contains so much potential for grotesquerie that there is no need for orcs or dwarves. Instead we are shown a vision of humanity at its most diverse and perplexing. Physical and mental deformity abounds; and yet beneath Peake’s obvious delight in portraying the human being in all its astonishing variety he retains a quality of insight and sympathy for his creations that raises his work beyond technical brilliance into something warmer and more universal….

Although I have long since given up the attempt to copy Peake’s flamboyant style in my writing, I’m aware that I still owe him a considerable artistic debt. In finding my own style I have tried over the years to assimilate some of the ideas that have struck me most forcibly from my reading of the Titus books. One is the importance of place and its role—which may be as important as that of any character or more so—within the body of the story. Another is the sensual quality of words and the way in which they can be used to evoke physical responses. Another is the importance of sound and rhythm on the written page (I always read my work aloud as I write, as Peake did).