Serafin (Gene Kelly): Aren’t you interested in love?

Manuela (Judy Garland): No! I told you I was going to be married.

Before going into detail about this month’s movie (which has become a bit of a cult film among fans of 1940’s Technicolor musicals), I’d like to make a couple of recommendations to anyone who might be looking for hints on finding older films worth watching. I’ve kept two invaluable reference books on my bathroom reading shelf for the past couple of years. The first is Produced and Abandoned: The Best Films You’ve Never Seen, edited by Michael Sragow and published by Mercury House, Incorporated. This anthology contains about a hundred reviews by members of The National Society of Film Critics. Reviews range from a page and a half in length to Pauline Kael’s masterly 8-page review of Jonathan Demme’s Melvin and Howard. Films are grouped in fourteen broad categories (The Horror! The Horror!, Love in the Dark, Shades of Noir, etc.). With thirty of the best American critics writing about obscure films they love, one could hardly expect to be disappointed by either the reviews or the films chosen.

My second indispensable tome is The Entertainment Weekly Guide to the Greatest Movies Ever Made, published by Warner Books. No eight-page reviews here, but a thousand pithy, witty commentaries on a 100 notable films in each of 10 categories. Sure, the usual picks are here—Citizen Kane, This is Spinal Tap, Psycho, E.T., West Side Story, etc.—but with almost fifty different reviewers picking their favorites one winds up with a surprising number of lesser-known gems. Examples? In the Drama category, Glory. a powerful story of black soldiers in the Civil War, Lillian Gish in The Wind, Joan Crawford in Mildred Pierce, Douglas Sirk’s Written on the Wind, and Humphrey Bogart as a paranoid screenwriter in In a Lonely Place. Although short, the individual reviews manage to be just that—individual. The Entertainment Weekly Guide makes for compulsive reading. It might be dangerous in the hands of bathroom readers with no sense of time.

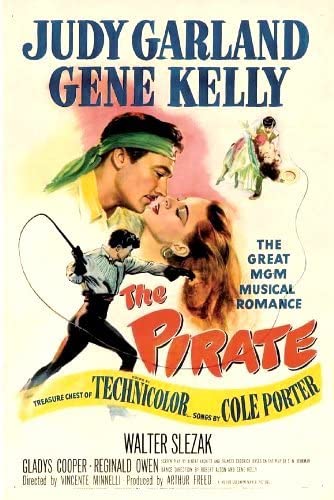

The section of the Guide that surprised me most was that devoted to musicals. I hardly ever seem to watch them, but as I read through the description of the dozens of starring vehicles for Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire, Judy Garland, Cyd Charisse, Mickey Rooney, Lena Horne, Jane Russell, etc., etc., I got to feeling that the next time I grabbed an armload of films there might be more swinging and less sub-titling. To test the waters, I picked up a copy of a 1948 musical I’d never heard of: The Pirate. Entertainment Weekly put it at number 24 in the Top 100. They got my attention when they mentioned that the film had the Nicholas Brothers “at their sharpest.”

The Nicholas Brothers at their dullest could blow your socks off.

I wrote about them a very long time ago, in a review of the all-black musical Stormy Weather (1943). To this day I don’t believe I’ve seen a more dazzling dance routine than the one Fayard and Harold Nicholas laid down at the end of that film. There’s some of that magic in the one number the brothers share with Gene Kelly in The Pirate, but I wish they’d had a whole lot more screen time.

There’s a simple reason they didn’t get it, however. In the racially charged atmosphere of the times, The Pirate is possibly the only movie where the Nicholas Brothers danced with a white performer. The usual routine was either to have all-black films like Stormy Weather and Cabin in the Sky (also 1943), or to keep black musical performers in separate “specialty” numbers that could easily be censored out for audiences in the Southern States. As it was, not even the presence of Gene Kelly could keep the Nicholas Brothers segment from “disappearing” when The Pirate was released in the South.

It’s said that Gene Kelly–who was responsible for getting the Nicholas Brothers into The Pirate in the first place–once complained that Harold was slacking off on a scene because he hadn’t been working on learnimg his routine. Harold responded by solo-dancing the entire scene flawlessly. That’s the kind of awesome talent that flashes through many of the old musicals (and some more modern ones) like diamonds.

For me, a real revelation of The Pirate was Gene Kelly’s performance as a dancing cross between Douglas Fairbanks and Groucho Marx. It takes chutzpah to be ham enough to live up to an intro like “The Glorious Adventures of Mack—The Black Macoco, Macoco the Dazzling, Macoco the Fabulous, the Hawk of the Sea, the Prince of Pirates, whose Spirit and Legend will live on through the Ages; a story staggering to the imagination and ravishing to the sensibilities—gold and silver beyond dreams of avarice, villages destroyed, cities decimated for a whim or a caress….” Well, you get the point. Needless to say, no cities are decimated and few imaginations are staggered. Kelly plays the role of Serafin the Great, a lovable rogue of an actor in a traveling vaudeville show who ends up being mistaken for the legendary “Mack the Black.” The Pirate isn’t Singin’ in the Rain (1952), but Gene Kelly is wonderful as a skirt-chasing scalawag who meets his match in Judy Garland’s Caribbean coquette. Kelly’s obviously having a lot of fun with his lines (“You’ll always need a bodyguard—even in the lonely wastes of the Sahara Desert the sands would rise up and follow you….”,”Fair Juliet of the Caribbean, have I walked the tightrope all the way to heaven?”), the Cole Porter songs (“Since I seen ya, Niña, Niña/I’ll be having neurasthenia/Till I make you mine”), and the choreography (surprisingly robust, set against Technicolor sets & costumes that could have been the joint creation of Lucille Ball, Bugsy Siegel and Salvador Dali). Kelly’s energy was boundless. In this same year that he was spoofing Douglas Fairbanks in a musical, he also swashbuckled as D’Artagnan in The Three Musketeers.

Judy Garland, too, is a joy in The Pirate, as she was in so many of her pictures. Made just as her addiction to diet and other pills was beginning to destroy her career, there’s no hint of the tragedies to come as Garland’s Manuela is naïve, sexy, meek, spunky, compliant and cheeky. My favorite scene is the one where she discovers Serafin’s deception (he’d led her to believe he was the dazzling Macoco of her dreams) and turns the tables on him by lamenting the fact that she could ever have mistaken him for anything as “unspeakably drab” as a common actor. Then she really rubs it in: “I should have known the first time I saw you that you knew absolutely nothing about acting!” Ouch.

Garland and Kelly have a genuine chemistry. Gene Kelly’s first film role had been in an earlier Judy Garland film, For Me and My Gal, made in 1942. Ironically, while Garland had been on stage all her life, Kelly began his career in the movies at the surprisingly late age of thirty. The director of The Pirate was Judy Garland’s second husband, the director Vincente Minnelli (father of Liza), with whom she’d also collaborated in Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), The Clock (1945), and Ziegfeld Follies (1946).

Rascals like Serafin (“base, proud, shallow, beggarly, three-suited, hundred-pound, filthy, worsted-stocking knaves” Shakespeare called them) never wear out their welcome. It’s fitting that the musical climax of The Pirate be the Kelly-Garland duet on “Be a Clown.” It’s advice the whole movie follows.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

For the life of me, I can’t recall why I originally chose to write about this movie. Honestly, it’s a bit of a cat’s breakfast. Ham acting, outrageous costuming, and set decoration that looks like it was randomly pillaged from several MGM warehouses. Musicians in the background scenes play everything from bagpipes to flutes to Arabian drums. If there were a leprechaun or two running around in the background, I wouldn’t be surprised. The setting is allegedly somewhere in the Caribbean, but a Caribbean dreamed up by Lewis Carroll. Even the phenomenal Nicholas Brothers get swallowed up in the madness. The Pirate is an outrageous confection, a giant demented wedding cake. No wonder that audiences couldn’t make heads nor tails of it when it was released, and that critics still can’t make their minds up if The Pirate is an embarrassment or, well, something else. Maybe Vincente Minnelli channeling Baz Luhrmann? This was supposed to be Cole Porter’s comeback film, but even with Garland and Kelly singing the heck out of “Be a Clown,” a love song that manages to find rhymes for “neurasthenia” and “schizophrenia,” and Gene Kelly’s virtuoso choreography for “Niña,” no one paid much attention at the time. Porter would make his real comeback later the same year with Kiss Me, Kate.

Upon reflection, I think was just struck by Judy Garland’s beauty and Gene Kelly’s effortless grace.

Garland is sexy here, and Kelly is the perfect, irresistible rogue. The first take of their “voodoo” dance number was so provocative that Louis B. Mayer ordered the negatives destroyed and the entire scene was redone. Even in a bowdlerized version, though, that scene still got some fire to it. This 26-year-old woman isn’t the Judy Garland of The Wizard of Oz. Good for her. Garland was going through some hard times when she made this picture. Her attendance on set was erratic, and her marriage to Minnelli was in its death throes. To her credit, none of this backstage drama shows through in her performances. I think she must have enjoyed working with as consummate a performer as Kelly. His talent was a match for hers, and sparks flew. Their one passionate kiss has its own YouTube video.

Whatever its flaws or failed ambitions, I still recommend The Pirate. There’s nothing quite like it.

They definitely don’t make them like this anymore.

Critic Pauline Kael described The Pirate as “flamboyant in an innocent and lively way. Though it doesn’t quite work, and it’s all a bit broad, it doesn’t sour in the memory.” Victoria Large, at the Bright Lights Film Journal, called the movie “loopy, knowingly campy, brightly colored, ambitious, and absolutely unique…a risky piece of work perfect for those who prefer the strange and daring over the formulaic.” More from Ms. Large’s short essay on The Pirate:

Along with the amusing, Pepe Le Pew-like solo number “Nina,” Kelly is afforded the sort of fantasy sequence that both he and Minnelli gravitated towards throughout their time at MGM. In this case it’s the gravity-defying “Pirate Ballet,” which features Serafin surrounded by an absurdly over-the-top amount of fire and smoke (the scene would be parodied later in Minnelli’s classic The Band Wagon). Best of all, Kelly performs an acrobatic dance routine with Harold and Fayard Nicholas when first introducing “Be a Clown.” The Nicholas Brothers were a great African American tap-dancing duo relegated to being a ” specialty act” in most all of their movies, their numbers strategically positioned so that they might be deleted from prints shipped to the American South without disrupting a given film’s continuity. The duo’s greatest cinematic triumph may be their heart-stopping contribution to the finale of Twentieth Century-Fox’s all-black musical Stormy Weather, but their desegregated appearance in The Pirate — a climactic moment not designed for excision — is a different kind of triumph. Kelly reportedly requested the Nicholas Brothers for the film and battled with the studio to get them cast. That he dared to speak out in favor of the duo is admirable. That he dared to dance with them without fear of being shown up is awfully gutsy.

Garland, meanwhile, is given a rare opportunity with Manuela. She gets to play a woman who ultimately bucks tradition and repression to assert her own desires. One her best moments in this film, and in any film period, is the lusty number “Mack the Black,” in which a hypnotized Manuela sings about her love for the dread Macoco. As Garland belts out the song, she is whirled about the set by a bevy of males, her long red hair trailing behind her like wildfire. Porter’s lyrics here are a riot: “Throughout the Caribbean and vicinity/Macoco leaves a flaming trail of masculinity,” Manuela informs us. It’s a great bit of unleashed ardor that might have freed Garland from playing the good girl once and for all, had anyone actually seen it. Unlike Meet Me in St. Louis or The Wizard of Oz, which found Garland playing a chaste girl innocently seeking happiness in her own backyard, The Pirate allows her to seize passion and adulthood. Manuela will never be content staying home.

Critic Fernando F. Croce wrote that “the brash saltimbanque (Gene Kelly) sweeps into town like a fusion of Fairbanks and Nijinsky, blithely wooing every belle in sight. (Kelly in curly pompadour and brown tights is out of Toulouse-Lautrec, with a Rousseau stage in a pavilion amid poles striped scarlet and white.)” Derek Winnert noted that “The troubled Garland, smoking four packs of cigarettes a day during filming, missed 99 of the 135 shooting days due to illness. Her struggles with prescription drug addiction led to several angry confrontations with husband/director Minnelli. Sadly, after all the hard work, it lost $2,290,000.”

French critic Erick Maurel had high praise for the film:

Après Lame de fond, un ratage total (le réalisateur n’ayant que trop peu d’affinités avec le film noir), Vincente Minnelli revient à la comédie musicale et nous livre un nouveau sommet du genre, une sorte de pendant survitaminé à son délicat Yolanda and the Thief qui aborde une fois encore le sujet des faux semblants, des jeux de dupes et de la dualité entre rêve et réalité. Avec d’énormes moyens (peut-être le plus gros budget de sa carrière), il prend d’énormes risques avec un tournage exclusivement en studio sans aucun plan d’extérieur réel – à l’exception d’un seul qui semble ainsi paradoxalement irréel et fantasmé – et un ton tout à fait nouveau pour le genre. En effet, nous sommes ici plus dans la comedia dell’arte avec sa joyeuse frénésie, son cabotinage excessif et son exubérance constante que jamais auparavant dans le musical hollywoodien, sans que cela ne soit pénible un seul instant puisque le sujet s’y prête admirablement, les protagonistes étant des saltimbanques ou de grands rêveurs romantiques qui cherchent à se duper chacun leur tour, non pour de viles raisons financières ou mercantiles mais par amour.

Déjà remarqué dans le poignant For Me and My Gal, le couple formé par Judy Garland et Gene Kelly fonctionne à merveille et tous deux rivalisent ici de talent dans le cabotinage pour notre plus grand plaisir. Judy Garland chante divinement et laisse exploser toute sa féminité et sa sensualité dans le morceau Mack the Black. Mais c’est à Gene Kelly que reviennent les séquences musicales les plus spectaculaires : le sublime Nina et ses plans séquences hallucinants de virtuosité et de fluidité ainsi que The Pirate Ballet pour lequel Minnelli nous offre un véritable feu d’artifice visuel. Au niveau musical encore (la musique signée Cole Porter ne doit pas excéder 10 % du film pour ceux qui seraient réfractaires au genre) : les touchants You Can Do No Wrong et Love of My Life chantées par Judy Garland, et le célèbre numéro final Be A Clown qui termine le film par un éclat de rire communicatif et surtout émouvant tellement il semble venu naturellement. On n’oubliera pas un excellent second rôle en la personne de Walter Slezak, qui nous ferait presque avoir pitié de son personnage lorsque Minnelli filme son visage démonté en gros plans lors de la séquence du procès, ainsi que la perfection du travail fourni par les équipes techniques et artistiques de la MGM – avec une mention spéciale aux décorateurs et aux costumiers. Comédie musicale originale, novatrice et ô combien culottée, Le Pirate réussit à combler de bout en bout de ces 100 minutes ceux qui accepteront de rentrer dans ce spectacle théâtral, bruyant, dynamique, surjoué et survolté.