“Do you know the secret of my success with tigers?”

– Janet Frame

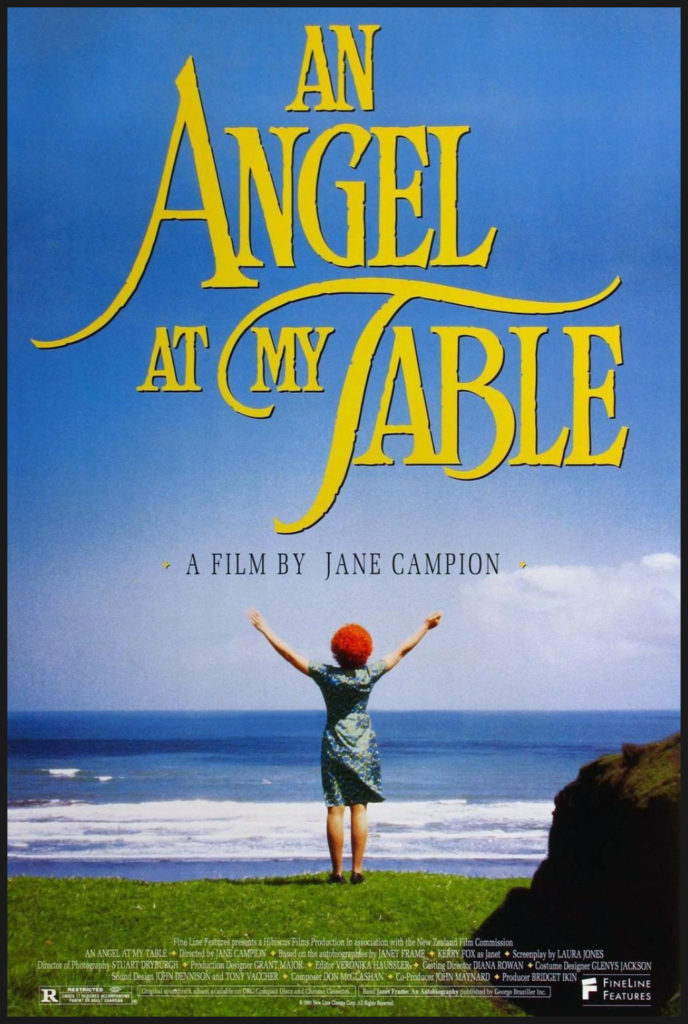

If you weren’t sure that there really was such a thing as karma, this month’s Seldom Scene might help. Yes, it could be a mere coincidence that last month’s film was called The Devil’s Eye, and this month’s is An Angel at my Table. It could be mere random chance …. but it’s probably not. In The Devil’s Eye, the cynical, defiant womanizer, Don Juan, finds himself in Hell as payment for a singularly selfish life; in An Angel at my Table, a singularly unselfish young woman is eventually saved from a much more literal hell by the guardian angels of her own imagination.

An Angel at my Table is based on the autobiographical writings of New Zealand’s Janet Frame, who survived societal straitjackets, multiple personal tragedies, and eight years of electroshock treatments (“200 of them, each equivalent in fear to an electrocution”) in a psychiatric ward, to become one of the finest writers of her generation. Unlike Sylvia Plath and Diane Arbus — two other gifted women who lost themselves in their nightmares — Janet Frame woke from troubled sleep to enjoy the ultimate triumph of a long, productive creative life. And if that sounds like more than enough raw material for an inspirational film …. you’re right.

The way director Jane Campion put tie film together gives it the visceral reality of a life in progress, rather than the sort of smug look back on the “bad old days” that might have tempted a less competent filmmaker. Remember Coal Miner’s Daughter, the movie based on Loretta Lynn’s autobiography? Not a bad film (and certainly a story worth telling), Coal Miner’s Daughter predictably had more of Nashville in it than it had of coal mines. An Angel at my Table is the coal mine. Or at least a writer’s version of it. If one substituted in children or class struggle in place of Janet Frame’s faith in literature, Angel might easily be a life story of a Kentucky miner’s wife. There is a grittiness in the film that is the antithesis of the kinds of sanitized, airbrushed, embellished, huge biographies that Hollywood is fond of producing.

No one in Angel is glamorous. The young Jane is a husky, grumpy Shirley Temple. The mature Jane might be any millworker. We care about all the characters in this film because, like actual human beings, they are vulnerable and imperfect. They remind one of people one knows.

There are no grand gestures, just poignant and significant ones. Rubbing a mother’s tired feet. Stepping in an absent father’s shoes. Listening to a teacher recite Tennyson’s poetry and making you believe it can change a life. And an interlude with the scariest piece of chalk in the history of cinema.

Angel is also a very crowded film. It is perhaps the most crowded film I have seen in a long time. Not simply because there are a lot of characters in it, but because the physical spaces are so compressed. Scenes are reminiscent of prairie life two generations back. Four children to a bed in a three-room farmhouse. Forty children to a room in a one- room schoolhouse. Hospital inmates crowded together regardless of disabilities— mental or physical. A traveller’s life lived in attic garrets and hole-in-the-wall tenements. The story ending (happily) back in the small, crowded-with-memories house where Janet Frame was born.

An Angel at my Table is inspirational because it shows how something so seemingly ephemeral as writing — words scribbled in notebooks and on scraps of paper — can cheat madness and death. Kerry Fox is superb in the role of Janet. Hopefully the film will encourage viewers to read some of Janet Frame’s own work. The novels, short stories, poems and autobiographies often walk the eerie borderlands between poetry and prose — the strangeness of the stories matching the strangeness of their titles: “Toward the Island”, “How Can I Get in Touch With Persia?”, “The Envoy from Mirror City”, “The Mythmaker’s Office”, “Scented Gardens for the Blind”, “Yellow Flowers in the Antipodean Room”.

No matter how odd the tellings, Janet Frame’s voices speak for all of us. Like the voices from Shakespeare she calls on to describe the “lost years” in the asylum:

Prospero: My brave spirit!

Who was so firm, so constant, that this coil

Would not affect his reason ?

Ariel: Not a soul

But felt a fever of the mad, and play’d

Some tricks of desperation.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

“I think of my heroines as going into the underworld in a struggle to make sense of their lives. I think the real danger is in playing safe and avoiding the truth of your imagination in your art and in your life.” –Jane Campion

One of the things that struck me most forcibly on watching Campion’s film again after so many years was how intimate it is. So much of Angel is close-ups and medium shots. Characters are often in one another’s personal spaces. A typical scene has the four Frame children in bed together, playing a game where they’re rolling backwards and forwards under the heavy covers. Such intimacy is appropriate considering the family’s relative poverty—at one point they lived in a collection of largely unheated, six-by-eight-foot railroad huts. An extra family member—grandmother, aunt—was often part of the household. Nature played such an important role in the children’s lives because it gave them room to breathe and move.

The film’s intimacy continues, in a terrifying way, with her eight-year stay in the asylum. The loving claustrophobia of a large family in small homes is replaced with the chaotic fishbowl of life in the crowded wards. The 200 electroshock treatments are the ultimate invasion of personal space (“each one equivalent in fear to an execution”). How did her mind and spirit survive? Like Dracula’s “The Blood is the Life,” for Janet Frame it was “The Word is the Life.” Her head was filled with the poems and songs she’d memorized, and no one could rob her of these. Her life story is one of the best arguments ever for public school teachers going back to making students memorize great poetry. And as a matter of fact, I think there is a growing wind in that particular pedagogical sail. “The Word is the Life” also applies to the publication of Frame’s first book, The Lagoon and Other Stories. Published while she was still in the asylum, its appearance saved her from a scheduled leucotomy.

The final intimacy is that of her affair with an American teacher, an irruption of real world romance into that of her love affair with poetry and literature.

The second thing that struck me this time around was how superbly and seamlessly the three (actresses Kerry Fox, Alexia Keogh, Karen Fergusson—all in debut roles) captured Janet Frame at the three different times of her life corresponding to the three volumes of her autobiography. Kerry Fox, in particular, garnered some exceptional reviews.

The third thing that impressed me was the vibrancy of the colours in this film—from the red fireball of Janet’s hair to the lush greens of New Zealand landscapes to the technicolor of Spanish towns. Cinematographer Stuart Dryburgh brings out the richness of the colour palette that Jane Campion wanted to use to counterbalance the melancholy and loss that suffused so much of the story. To stay true to the books, the film had to glow like embers and be lucent as dreams.

The musical score by Don McGlashan is lovely—harpsichords, pennywhistles, piano, popular songs, children’s songs, Schubert and Tchaikovsky—an eclectic mix that matches the shifting time frames and the transitions in Janet Frame’s life.

As one must with any impressive film set in the past, one has to acknowledge the invaluable work of the Production Designer, Grant Major. and Costume Designer, Glenys Jackson.

Two of my favourite scenes, capturing the playful/joyful side of To the Is-Land, were the ones where children were auditioning for a small stage role (they had one line to deliver: “Look out, there’s dynamite down there”), and where Janet’s junior high school teacher, Miss Lindsay (Edith Campion), gives a mesmerizing recital of lines from Tennyson’s Idylls of the King and absolutely makes us believe that a moment such as this can change a student’s life. Later in her autobiography, Frame will refer to “Miss Lindsay of the ‘jewelled sword Excalibur and the hand clothed in white samite mystic, wonderful’”. There will be other memorable encounters with Sir Walter Scott’s The Lay of the Last Minstrel and Coleridge’s The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner, Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale, and Alfred Noyes’ “The Old Grey Squirrel.”

As fine as An Angel at My Table is, it should just be a teaser to draw you in to the extraordinarily detailed world of Frame’s autobiographical writings. Here are fragments not found in the film, all from To the Is-Land:

“There was one other child known as ‘dirty’: Nora Bone, whom I despised because she, like myself, was seldom asked to join the skipping, but whose need was so strong that she always offered to ‘core for ever’, that is, turn and turn the skipping rope and never herself join in the skipping. She was known as ‘the girl who cores for ever’. There were only two or three in the whole school, and everyone treated them contemptuously. Nora Bone, the girl who cores for ever. There was no more demeaning role. No matter how much I longed to join in the games, I never offered to core for ever.”

“Mother in a constant state of family immersion even to the material evidence of the wet patch in front of her dress where she leaned over the sink, washing dishes, or over the copper and washtub, or, kneeling, wiped the floor with oddly shaped floorcloths—old pyjama legs, arms and tails of worn shirts—or, to keep at bay the headache and tiredness of the hot summer, the vinegar-soaked rag she wrapped around her forehead: an immersion so deep that I achieved the opposite effect of making her seem to be seldom at home, in the present tense, or like an unreal person with her real self washed away….When Mother talked of the present, however, bring her sense of wondrous contemplation to the ordinary world we knew, we listened, feeling the mystery and the magic. She had only to say of any commonplace object, ‘Look, kiddies, a stone’ to fill that stone with a wonder as if it were a holy object. She was able to imbue every insect, blade of grass, flower, the dangers and grandeurs of weather and the seasons, with a memorable importance along with a kind of uncertainty and humility that led us to ponder and try to discover the heart of everything. Mother, fond of poetry and reading, writing, and reciting it, communicated to us that same feeling about the world of the written and spoken word.”

“…in the warm of the kitchen hut Mother would play her accordion and sing while Dad, sometimes striding up and down in the snow (he insisted that you had to stride up and down while you played the bagpipes), played his bagpipe tunes–‘The Cock o’ the North’ or ‘The Flowers of the Forest’ or other from his book of bagpipe music….We recited out favourite poems, too—‘Old Meg She Was a Gypsy’, ‘I Met at Eve the Prince of Sleep’, and Myrtle sang her special songs, including ‘By the Light o’ the Peat Fire Flame’ and ‘The Minstrel Boy to the was has gone / In the ranks of death you’ll find him’, singing it as if the Minstrel boy were a boyfriend of hers, which I half believed him to be.”

“…at the music festival, Shirley [the girl whom Janet’s teachers praised for her imagination and her poetry] sang ‘To Music’, from our Dominion Song Book.

Thou holy art in many hours of sadness

When life’s hard toil my spirit hath oppressed…

I felt that I had never heard such a beautiful song, both in the piano accompaniment and the words. I learned at the festival that Shirley also played the piano…And then, to make perfect Shirley’s enviable endowment, her father died, and while Shirley was absent, the teacher told us about the death and reminded us to be kind to Shirley because her father had died.

I was overcome with envy and longing. Shirley had everything a poet needed plus the tragedy of the dead father. How could I ever be a poet when I was practical, never abstentminded, I liked mathematics, and my parent were alive?”