“I believe we’re doing this for your own good.” If one were a patient in an insane asylum in Europe or North America in the mid-1800s, that kind of comment from one’s doctor might have pushed depression over into suicide. We are speaking of a time when asylums could be more brutal than today’s maximum security prisons, the mentally ill were often viewed as sub-human fodder for experimentation, inmates were force-fed alcohol to keep them docile, and an “acceptable” treatment for female “hysteria” consisted of the removal of the patient’s ovaries. By the general public, the local asylum was seen as a Gothic castle-on-the-hill filled with creatures best kept locked away from the sight of genteel eyes.

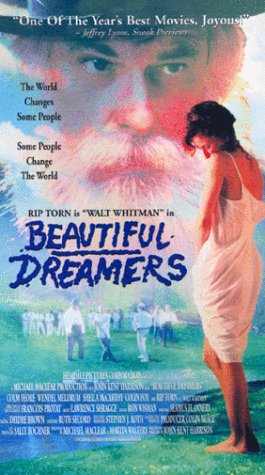

We’ve made progress since then. The fine Canadian film Beautiful Dreamers (1990), written and directed by John Kent Harrison, tells of the kind of individual courage and vision it took to free the insane from their (literal) chains and bring them out of the (literal) darkness. Along the way it also tells us about a fascinating Canadian historical figure most of us have never heard of, about the wife who probably wished her husband were less fascinating, and about Walt Whitman.

It’s as unlikely a narrative as any Bob Johnston tells on early morning CBC radio: a thirty-year-old Canadian physician, Richard Maurice Bucke (Colm Feore), recently appointed superintendent of the London (Ontario) Asylum for the Insane, travels to Philadelphia for a medical conference on the treatment of madness. Walking out in disgust at the inhumanity of the treatments being described, Bucke is hailed in the street by a white-bearded dynamo who’s walked out for the same reason. The dynamo turns out to be America’s greatest poet, Walt Whitman (superbly played by veteran character actor Rip Torn). The chance meeting reshapes both their lives. Whitman finds a devoted friend and future biographer. Bucke finds in Whitman’s vision of humanity inspiration for his struggle to bring some measure of dignity and joy to his patients.

For Bucke, the lessons begin with the first few days spend at Whitman’s home in Camden. He sees Whitman’s loving treatment of his own mentally challenged brother, Eddy—they play together like children in Whitman’s home and in the fields near the house. These scenes with Eddy remain among my personal favorites. Walt tells Eddy, in lines which will be echoed at the end of the film, “You make me rich, rich like a king.” The words and scenes incarnate the Walt Whitman I’ve always imagined from the reading of his poems. Standing in the sun and the tall grass, Whitman tells Bucke what really matters:

“I reckon all a man’s gotta do is love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to everyone that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God…Take off your hat to nothing known or unknown or to any man or number of men, go freely with powerful uneducated persons and with the young and with the mothers of families, read these leaves [actual leaves, or Leaves of Grass, Whitman’s revolutionary anthology of free-verse poetry? both?] in the open air every season of every year of your life, re-examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book, dismiss whatever insults your own soul…”

That’s all.

Unfortunately, one person’s inspiration is another person’s excrement. Whitman was not welcome in the proper English circles of London society. Let’s face it, Walt not only wrote candidly about the body, about sex, and about democracy, but he was also rumored to be an atheist. On top of it all, his poems didn’t even rhyme. They’d been branded as “coarse indecencies” and banned in Boston. As one terribly respectable Londoner comments, “Friendly people, the Americans. No breeding, though. Not the sort of people we want telling us what to do. Not in the Dominion, at any rate.” A London priest fulminates from the pulpit against bad literature and evil companions, dreading a cultural apocalypse (“The guillotine has a new blade, and it’s very, very sharp”). As for Bucke’s idea that the asylum patients might be allowed out for exercise and given the chance to have fun, play sports, listen to music, etc….well, the mayor of London informs him that he wants a man at the asylum that can do the job, not change it. “LOONIES FREE!!” screams the headline in the local paper.

Bucke’s wife Jessie (Wendel Meldrum) is caught in the crossfire. At first she’s deeply suspicious of Whitman’s poetry, heeding the warnings of close friends. Later she’s depressed and jealous of the intimate kinship between Walt and Bucke that threatens to cut her adrift. In the end, Jessie comes to embrace in Whitman the same boundless humanity that has — her husband. Like Bucke’s patients, she too finds herself released from restraints.

This story has a happen ending. It involves an unusual cricket match and an unorthodox public picnic. Getting us that ending are some strong performances by Sheila McCarthy and Tom McCamus as inmates of the asylum.

Watch this film. Go out and read some Walt. Lend someone a helping hand. The Reverend Blaine was right, though. This can be dangerous stuff. Like Bucke and Jessie, you could wind up naked in a river, singing opera to the trees.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

For some of us, these seem like dark days. The social compact that has been built upon the blood and sweat and tears of so many is being challenged by a rising tide of intolerance, bigotry, arrogance, self-interest, jingoism, lies, and propaganda. This certainly isn’t the best that we can be, and we’re going to see how much damage small minds can do when they fill big shoes. Beautiful Dreamers is a bright movie for dark times. It serves as a reminder that there will always be voices speaking out for the better angels of our nature, insisting upon our common humanity when others preach nothing but ignorant armies clashing by night. The American Civil War did not end America; what came after was an America one step closer to the kind of democracy that Walt Whitman believed it would become. The horrors did not end—racism, imperialism, exploitation of labour, environmental despoliation—but along the way the suffrage became universal, labour became unionized, welfare & unemployment programs began to protect the most vulnerable, contraception changed the sexual landscape. Nor did the nightmare period of the Civil War crush the arts—Herman Melville, Emily Dickinson, and Whitman were at the height of their powers.

Beautiful Dreamers gives us a glimpse of how far we can come. Go back 150 years and we’re in a time when the insane could be packed around in man-sized equivalents of lobster traps, kept in permanent restraints, beaten at will, kept sedated by alcohol, and never allowed out into the light of day. Women patients were regarded as prone to hysteria and nymphomania, and the “cure” was incarceration and the surgical removal of the clitoris and the ovaries. That a woman might be having a mental breakdown simply because she was overworked and physically abused wouldn’t have been considered by physicians. In the 25 years that Richard Maurice Bucke was the superintendent of the London, Ontario asylum—one of the largest in North America with over 900 patients, most of them from the class of working poor—he saw to the almost complete removal of restraints, developed treatments that would now be classed as occupational therapy, encouraged therapeutic play, supported music & art for the benefit of patients, abandoned the use of alcohol, and gave patients free access to the asylum grounds. In only one area of treatment did Bucke seem a product of his times—he never lost his faith in surgery as a treatment for insanity in female patients. Some would damn him for this alone.

We’re used to biographical movies magnifying the achievements or vices of their characters. In the cases of Walt Whitman and Richard Bucke, however, such exaggeration is hardly possible. Impressive as Rip Torn’s performance is in Beautiful Losers, it cannot take the full measure of the man. Whitman is bigger than the movies. The devotion he inspired in so many, and the loathing he inspired in others, needs volumes to explore. Bucke himself spent 15 years in close contact with Whitman, eventually becoming his official biographer. Colm Feore does an excellent job conveying Bucke’s passionate advocacy of his spiritual mentor, yet Beautiful Dreamers ends where their relationship only began. Nor do we get the full measure of Bucke himself. He fathered eight children, ran the massive London asylum, acted as Whitman’s Boswell & his literary executor, founded the School of Medicine at the University of Western Ontario, and wrote enormously popular books on what he saw as the coming revolution in human consciousness.

In the film, Bucke’s wife also eventually comes to share his enthusiasm for Walt and his pantheistic embrace of life. I’m not sure that happened. Never mind the fear of her husband’s affections being alienated, even the film’s asparagus-eating scene might have been too much for her. But because everyone involved with the movie opened my eyes to a story I had been utterly unaware of despite my love for Whitman’s poetry, I’m willing to forgive some creative licence. And if Whitman didn’t pull off an intellectual seduction of Mrs. Bucke, he was certainly capable of it. Here’s what a Chicago woman, a complete stranger, wrote to Whitman in 1882: “I have loved you for years with my whole heart and soul. No man ever lived whom I have so desired to take by the hand as you. I read Leaves of Grass, and got new conceptions of the dignity and beauty of my own body and of the bodies of other people, and life became more valuable in consequence.” This is the Walt Whitman that is at the heart of Beautiful Losers.

Walt has his movie. Keats has Bright Star. When will someone finally put Edgar Allen Poe and Emily Dickinson on the screen in a way that does justice to their genius?

There’s a good outline of Richard Bucke’s life online at the Canadian Dictionary of Biography website. Below is an edited version of Justin Kaplan’s description of Bucke in Walt Whitman: A Life:

Richard Maurice Bucke, a physician and eminent alienist…was Whitman’s Luke as well as his Paul, missionary to the gentiles and to far-flung congregations of true believers….The doctor had arrived at Camden for a visit just in time to respond to what was clearly the mortal emergency of Whitman’s collapse in June 1988. “He took off his coat, rolled up his sleeves, buckled to, saved me,” Whitman said a week and a half later. “I thought I was having my last little dance.” Bucke’s devotion was so intense and of such long standing that over the years he came to look like Whitman. Sometimes he even fancied he was Whitman, although in essential respects their personalities were antithetic….”I must confess he has plastered it on pretty thick,” he said once, after Bucke had lectured on Leaves of Grass before the Ethical Culture Society of Philadelphia, “plastered it on not only a good deal more than I deserve but a good deal more than I like.” “I fear he lacks balance and proportion,” said John Burroughs, the most levelheaded member of Whitman’s circle…Choleric and peremptory, with a voice that had a “shrieking quality,” Bucke was nonetheless, in Whitman’s grateful opinion, “a whole man—he has lived own his losses,” which included the whole of one foot and the toes of another, amputated long ago when he nearly died of exposure and starvation attempting to cross the Sierra Nevada in winter. As a young man Bucke had been a railroad hand, a wagon-train driver, and a miner in the Utah and Nevada Territories; he once stood off for half a day a Shoshonee war party on the banks of the Humboldt River. He knew at first hand the frontier America that Whitman chiefly knew in imagination.

Bucke’s discovery of Leaves of Grass in 1868, when he was thirty, was the first in a series of events that bound him to Whitman and his work for life and, he believed, perhaps even for eternity….In 1872, after an evening spent reading Whitman, Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats and Browning, Bucke experienced what he described as an unforgettable, never-to-be repeated moment of “illumination,” “exultation,” “Brahmic Splendor,” and “immense joyousness. He felt he was at the center of a “flame-colored cloud.” He “knew,” in a way in which he had known nothing before, that “the foundation principle of the world is what we call love, and that the happiness of everyone is in the long run absolutely certain.” From that ecstatic moment on, Bucke, like the hedgehog, knew one great thing and knew it very well.

He met Whitman face to face for the first time in 1877 and—like other who came to Camden and were exposed to the strangely affective personality in residence there—experienced “a sort of spiritual intoxication.” Until he died, twenty-five years later, he devoted himself to the study of spiritual evolution, publishing two books on the subject, Man’s Moral Nature (1879) and Cosmic Consciousness (1901), in addition to a biography of Whitman (1883). He had found that ecstatic illuminations were by no means so uncommon as supposed—ordinary people leading ordinary lives testified to them as well as great moral and ethical leaders….