“Somehow everything comes with an expiry date. Swordfish expire. Meat sauce expires. Even cling film expires. Is there anything in the world which doesn’t?”

–Badge No. 223, in Chungking Express

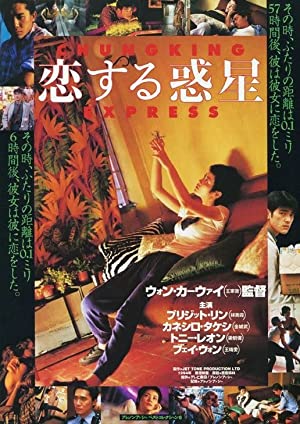

I think Trout Fishing in America Shorty would have felt right at home in Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wai’s Chungking Express (1994). Shorty was a character in one of the earliest of Richard Brautigan’s 1960’s bittersweet, oddball prose-poem meditations on things lost, things found, and things that the wind blows away. One of those things is love. The best of Brautigan’s work was always more sweet than bitter, and Chungking Express has two of the quirkiest, sweetest love stories I’ve seen on film in a long time. I loved one critic’s description of it as “a stylish film about sensitive boys who miss their girlfriends, and don’t blow anything up.”

I came across it while trying to check out some of the Hong Kong films that have been having an impact on North American cinema over the last decade or so. I picked up Wong Kar-Wai’s film just after watching John Woo’s ultra-violent, ballistic homage to spaghetti westerns, Hard-Boiled (1992), and Ronny Yu’s surrealist, equally ballistic The Bride with White Hair (1993). By that point I was so traumatized (Quentin Tarantino’s comment on John Woo: “Yeah, he can direct an action scene, and Michelangelo could paint a ceiling”) that I was wondering if I needed a seat belt on my couch. With Chungking Express, instead of bullets I got Brautigan.

Well, to be honest, Brautigan with just a few bullets. The first of Chungking Express’s two stories does involves drug smuggling and gunplay. It’s just that those plot elements are so much less important than the hopeless romanticism and the metaphors about canned pineapples and expiry dates. Sound confusing? It is. Would you need to watch this movie twice? Probably. Unless, of course, you finish reading this review and get a key to the labyrinth.

Both love stories in Chungking Express involve young policemen who’ve just lost lovers. The setting in the first story is Chungking Mansions, a huge multilingual warren of tenements, vindaloo shops, and electronics bazaars. Linking both stories is a Chinese fast-food take-out called the Midnight Express. The whole film is lit by neon and fluorescent light, it’s almost always night and sometimes raining, and sunlight seems an alien concept. The typical view out a window is of an escalator where a street should be. The handheld camerawork (the only kind there is here) gives the film a claustrophobic, nervous energy and the jarring visual definition of a string of urban haikus about lives spinning just on the edge of control. Had Wong Kar-Wai not had the sense of humor he does, I would have been reaching looking for a seatbelt again.

In story number one, Badge No. 223 (Takeshi Kaneshiro) has just been dumped by May, his girlfriend of five years. The breakup happened on April Fool’s Day, and he’s giving her until May 1st to admit it was just a cruel joke. To mark the time, each day he buys a can of pineapple with a May 1st expiration date. If May doesn’t call his pager by then, the love affair will also have expired. I love the naïve, wacked-out metaphors in Wong Kar-Wai’s film. To take his mind off his heartbreak, No. 223 says he goes jogging because that way he’ll sweat out the water that would otherwise go into tears. A wonderful thing about this film is that you actually believe him when he says that, just like you believe all of the other characters when they talk to bars of soap and dishrags. Just like we believed those letters from Trout Fishing in America Shorty.

No. 223 shares his troubles with the owner of the Midnight Express (Piggy Chan), who tells him to get on with his life. May 1st arrives and realization dawns: “In May’s eyes I’m no different from a can of pineapple.” Finally giving up on checking his pager for nonexistent messages (password: “undying love”), Kaneshiro tries dialing up old girlfriends. It’s been a while–they’re now married with children or haven’t heard from him since grade 4.

In desperation, he goes into a bar and vows to fall in love with the first woman who walks in. He’s become fascinated by the idea that lives intersect in seemingly random ways. The woman in the bar turns out to be Brigitte Lin, in a trench coat, sunglasses, and a blond wig (Brigitte Lin Chin-hsia is a legendary star of over a100 films, including The Bride with White Hair, and is at ease with gun, whip, and sword; this was her last film before her unexpected retirement). Lin’s character is on the run from a botched drug smuggling deal that ended in murder. No. 223 is blessedly ignorant of any of this. His pickup line is: “Excuse me, Miss, do you like pineapple?” His follow-up: “Wanna go jogging?” Don’t laugh, it works. Except that it leads to something much more innocent than a one-night stand.

It also leads back to pineapples: “[May] says I don’t understand her, so I want to find out more about you.” –“You’ll find out nothing. Knowing someone doesn’t mean keeping them. People change. A person may like pineapple today…and something else tomorrow.”

I’ve long suspected that pineapple and heartbreak weren’t mutually exclusive.

Chef salad is also pretty important. It kind of kicks off the second love story. The policeman this time is No. 633, played by Tony Leung Chiu-Wai (who also stars in Woo’s Hard-Boiled). Tony asks the owner of the Midnight Express what kind of snack he should take up for his stewardess girlfriend. They’re in the midst of a torrid affair. The boss recommends giving her a choice, instead of Tony’s usual chef salad. A few meals later, the girlfriend’s gone, there’s a Dear John letter, and Tony ruefully remarks, “I guess I should have stuck with the chef salad.” He deals with depression by talking to things in his apartment. A bar of soap, for instance: “You’ve lost a lot of weight, you know. You used to be so chubby. Have more confidence in yourself!”

Meanwhile he’s caught the eye of a young girl, Faye, who works at the snack bar. She’s in her own world, bopping around to music like the Mama and the Papas’ “California Dreamin’” at full volume so she doesn’t have to think beyond the moment she’s in. Faye’s saving her money, and has some vague thoughts about going to California or somewhere, but until she meets Tony the music is all she needs. Played by Hong Kong pop superstar Faye Wong in her film debut, probably only someone as remarkably unobservant as Tony could manage not to fall in love with her immediately. Can you say joie de vivre in Cantonese?

Tony also fails to notice that someone’s started sneaking into his apartment and tidying it up when he’s on duty. It’s Faye, and she’s doing some serious obsessing here. With anyone else it would be downright creepy; with Faye it’s like being blessed by a bebop angel. Tony takes a long time to clue in. There are more wonky metaphors and conversations with bars of soap. And where does it all lead? To one of the most romantic endings since Humphrey Bogart said goodbye to Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca. It’s two weeks later and I’m still smiling at the memory.

Two of Chungking Express’ other pleasures are the soundtrack (including Faye Wong’s Chinese version of the Cranberries’ “Dreams”), and the Cantonese and Mandarin dialogue. I didn’t understand a word, but I heard everything they were saying.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Quentin Tarantino provides a fine short commentary on Chungking Express in one of the bonus features on the DVD. In particular, he’s right on the money when he says that there aren’t many viewers who can resist being charmed by the sight of Faye Wong behind a lunch counter, dancing in her own world as the power strains of “California Dreamin’” blast out of a CD player. The rewind button of my DVD player had a good workout for those scenes. Of course, they’ re on YouTube now. I watched them again as I was writing this. When I first fell in love with Faye, I had no idea that Ms. Wong was a pop superstar in Asia at the time she made the film. Her fame makes the grace of her self-effacing performance even more remarkable. Her performance is also a tribute to Kar-Wai Wong’s deft writing & direction. Faye Wong starred in only four films after making Chungking Express—choosing to focus her career on her music. Looking for her other films, I’ve been able to track down only a copy of Okinawa Rendezvous on YouTube.

Tony Chui-Wai Leung is equally endearing as melancholic Cop 663, in between girlfriends and reduced to mournful one-sided conversations with bars of soap, dish rags, and empty apartments. Tony Leung continues to have an outstanding career in film, with 100 acting credits on Imdb as of the end of 2021.

Stalkers in films are typically homicidal maniacs bent on wiping the objects of their obsession out of existence in the most blood-curdling ways possible. Faye might be the cinema’s first & only stalker with a heart of gold. She and Tony Leung’s oblique love affair stands as one of the coolest the cinema has to offer, a gentle light in dark times.

Kar-Wai Wong’s directing style here owes a lot to the French New Wave, but it also has the eclectic, endearing strangeness of Haruki Murakami’s early stories, such as Norwegian Wood and A Wild Sheep Chase. Kar-Wai Wong has made only a handful of feature films since 1994, the most successful of which was In the Mood for Love (2000, available for streaming on The Criterion Channel).

Veteran cinematographer Christopher Doyle has 100 film credits on Imdb, with 59 award wins & 49 other nominations.

If you’ve already watched Chungking Express, you’ll have noticed that in this update I’ve ignored the Brigitte Lin story that starts the film. Kari=Wai Wong originally planned his movie as a trilogy of stories, but dropped the third one during shooting. As much as I admire Brigitte Lin as an actress, her shorter opening segment of Chungking Express, while a cool exercise in style, pales next to the quirky romantic perfection of the Wong-Leung storyline. If you haven’t seen Chungking Express, take note that it’s the second story that you don’t want to miss. Although, now that I’ve looked back at my original review, I have to admit that the pineapple existentialism was a lot of fun.

Chungking Express was the first (and most successful?) of only a half-dozen movies released through Quentin Tarantino’s short-lived distribution company, Rolling Thunder Pictures, which shut down in 1999.

From Eastern Standard Time—a Guide to Asian Influence on American Culture: from Astro Boy to Zen Buddhism, by Jeff Yang, Dina Gan, Terry Hong & the staff of A. Magazine:

Wong Kar Wai: Odd Man In

Wong was a graphic design student at Hong Kong Polytechnic, before following a path taken by many of Kong Kong’s brightest entertainment names: He enrolled in a course at the Shaw Brothers’ TVB, and upon graduation received a job as a production assistant. He also began to indulge his desire to write, and went on to pen a number of scripts for top directors. Then, in 1989, he got the opportunity to helm his first picture—the rebel-without-a-cause gangster pic As Tears Go By, featuring singer Andy Lau and rising ingenue Maggie Cheung. The film was popular—but it also established him as a director capable of bringing out uniquely rich performances. In an industry where actors are routinely treated as commodities, Won was a revelation, and when he cast his followup, Days of Being Wild, every young actor in Hong Kong lined up for parts. The film, a steamy, dreamy collage of teen lives beset by ennui and unfulfilled desire, proved to be a turning point on two levels: it demonstrated to international audiences that Wong was a director worth watching, and it demonstrated to local studios that Wong was a director whose return on investment was going to be awards—not box office.

From Sex and Zen & A Bullet in the Head, by Stefan Hammond & Mike Wilkins:

Chungking Express has the relentless energy and inexplicable grace of a perfectly crafted pop song: its giddy rhythms and infectious melodies linger long, circling around memories of forgotten lovers and ill-fated romances, teasing at emotions you’d long ago misplaced. Passions cross, pursuits dead-end, and romances disconnect in this bright, buoyantly atypical HK art film.

CKExp was hot in Hong Kong’s Chungking Mansions—an enormous, rambling high-rise teeming wtih grotty Rough Guide backpacker’s hostels and filthy vindaloo joints. Its on-the-fly aesthetic is there a single tripod-mounted shot in the entire film?) captures the antic authenticity of HK’s bustling streetlife, putting its fast-forward realism in the service of a fresh arrangement of rambunctious ideas and gorgeous images (thanks to director Wong Kar-wai’s recurrent cameraman, the brilliant Australian, Christopher Doyle)….

While a plot synopsis barely begins to convey the assortment of visual riffs (mirrored images, smudgy chases, loopy body language) and thematic resonance, it is a fil filled with possibility and energy and a sense that, though the clock is ticking, time is forever expanding, and that—1997 notwithstanding—the future isn’t running out.

[NOTE: It’s not 2022. The Chinese government continues to crack down on dissidents. Is the future running out for directors like Kar-Wai Wong? I have yet to come across a book or article on the history of Hong Kong cinema in the post-1997 era.]

Available on YouTube? No, but available for streaming at criterionchannel.com