One of my most enduring memories of being a child in elementary school centers around the upright piano in the grade 5/6 classroom. In a sort of benign haunting, it would possess our homeroom teacher (also the principal of the school) whenever he sat down before it. A large, affable man, the touch of those 88 keys would steal away the stern disciplinarian who ran the classroom ship and leave us in the willing thrall of a barrelhouse refugee from a Klondike saloon. Lord, how that man could play! And, Lord, how he’d make us sing!

You get a line and I’ll get a pole,

Honey,

You get a line and I’ll get a pole,

Babe,

You get a line and I’ll get a pole,

We’ll go down to the crawdad hole,

Honey, sugar baby mine.

Did any of us know what a “crawdad” was? I doubt it. But as we gathered around the piano those songs—“Down in the Valley,” “The Blue-Tail Fly,” “Clementine,” “Red River Valley” and dozens of others—became, briefly or permanently, and indispensable part of our lives.

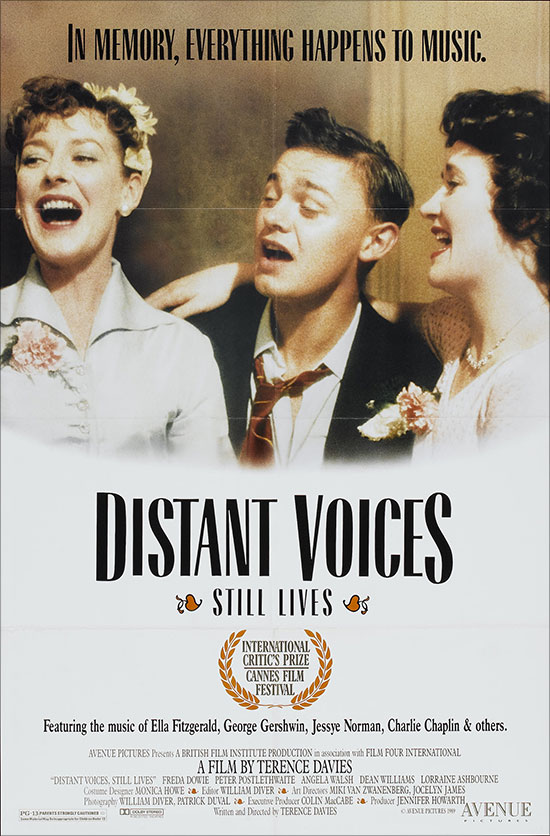

Terence Davies’ film Distant Voice, Still Lives (1988) is an astonishing film about another time (the 40s and 50s) and place (Liverpool, England) where popular songs linked people together more closely than the awkward words they spoke in affection or anger or shame. Distant Voices, Still Lives is most definitely not a musical, and yet there are more songs in this film than in almost any musical I know. Three dozen songs heard as background to deaths and losses, picked up with a casually cruel randomness on the radio (a battered wife, face & arms covered in bruises, painfully irons clothes to the tune of “Taking a Chance on Love”), or sung by the main characters in pubs, at weddings, in jail cells, and even while (“Up a Lazy River”) peeing in alleyways.

Davies and the actors he worked with make us care about all of the people in his film. And because we care about them, we remember the songs they choose to sing: “I Get the Blues When It’s Raining,” “If You Knew Susie Like I Know Susie,” “Bye Bye Blackbird,” “When Irish Eyes are Smiling,” “O Waly, Waly,” “The Finger of Suspicion,” “Barefoot Days,” “My YiddisheMama.” When daily life is marked by war, domestic violence, alcoholism, struggle for a decent life, and failed dreams, Tin Pan Alley lyrics seem as universal as Greek tragedy and every bit as potent. And let’s not forget the background music: Harold Darkes’ “In the Bleak Midwinter,” Benjamin Brittan’s “Hymn to the Virgin,” Vaughan William’s “Pastoral Symphony.” “There’s a Man Goin’ Round Taking Names” is the scariest spiritual since the Reverend Gary Davis’s “Death Don’t Have No Mercy.” If a soundtrack for this film exists, I want it. Right now.

In composition, Distant Voices, Still Lives is like a somber family photograph album that comes complete with its own soundtrack, but whose binding has come undone. Each photograph is beautifully composed and it; we’re just not sure about the chronology. The film almost demands two viewings: one to put the pages in order in one’s head, and the second to appreciate individual scenes as they become charged with our understanding of what has gone before or will happen after. I have no favorite scenes in Distant Voices. Every page, every photograph in this album is irreplaceable.

There is much more that is special about the film. Freda Dowie infuses the role of the mother with incredible dignity. Pete Postlewaithe is both terrifying & pathetic as the father whose only eloquence is rage. Angela Walsh, Lorraine Ashbourne, and Dean Williams are utterly convincing in their portrayal of siblings bound by love and hate. Also wonderful is Debi Jones as Walsh’s “bleedin’ dance-mad” friend, Micky. And Uncle “I switched the light off. I don’t know what I’m doin’ right or wrong-o” Ted, who has one of the strangest cameo appearances I’ve ever seen. Hardly household names, each of these actors turns in the kind of performance the Academy Awards are supposed to honour.

Sometimes the artifice that’s a part of exceptional works of art is obvious at first glance. Sometimes, however, artifice is felt before it is seen. Such is the case with Davies’ film. The first time I watched it, something about his use of the camera intrigued me—but I couldn’t articulate it. On second viewing, I think I understood. The camera in Distant Voices, Still Lives is immobile. It almost never pans. And in the rare moments when it does pan, it moves through time instead of space. In scene after scene, the camera is simply there. There in the room, there at the window, there sitting in front of a door looking out, or before a door looking in. I kept picturing one of those old-fashioned photographers, head under a hood behind a big camera on a tripod out in the street, with the whole family poised on the verandah, waiting for the flash. Such “motionless” photography simultaneously gives the individual characters in Distant Voices considerable dignity, and heightens the sense of claustrophobia which cripples them. “The joy you find here you borrow / You cannot keep it long it seems.”

Sort of like the movies selling us dreams, and real life stealing them away. In one of Distant Voices’ eeriest overlays, surrealist umbrellas lead the viewer into a theatre where the two sisters cry as they watch Love is a Many-Splendoured Thing. Then there is an exquisitely choreographed shot of two men falling through what might be real or might be cinematic space. Followed by the sight of one sister crying at the bedside of her husband, critically injured in a fall from a scaffold. The only thing we can be sure is not an illusion is the pain.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Sadly, this is another film I’ve been unable to get a hold of for another look. It goes on the list. Feel free to check back in later.