A TV’s just an egg. A house, now that’s a chicken.

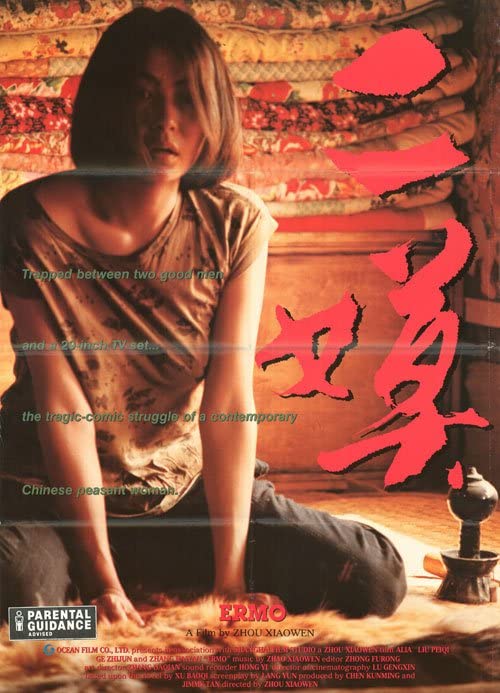

Ermo. Sounds like the latest craze at Toys’R Us. One of those weird-looking, vaguely sinister stuffed things that catch on faster than most computer viruses. Oh, the temptation. To walk into Wal-Mart, crumpled piece of paper in hand, desperate look in the eyes. Pleeeease, my children’s friends all have Ermos, can you help me? You know, they’re sort of a cross between Beanie Babies and Cabbage Patch dolls? I’m sure they said they bought them here….The poor clerk would probably have the same confused but earnest look that I got from every video store person between here and Castlegar. Ermo is actually the title of an astonishing Chinese film released in 1994. The eponymous heroine is one of the most memorable characters in recent cinema. This film is a gem, and at the moment the only place you’re going to find it locally is at Video Update in Castlegar.

Every now and then I like to grab three or four films at random out of the Classics or Foreign section of a video store. Ermo is by far the best of my recent random choices. This is not the Chinese cinema to which you may be accustomed. It doesn’t have the epic sweep of Farewell My Concubine, or the lethal intensity of Raise the Red Lantern. Ermo is a smaller, more intimate tale of human weakness and human courage.

Even in these days of endless talk of war in the Middle East and nuclear brinkmanship with North Korea, China can never be far from the thoughts of anyone looking at the global scene. The Industrial Revolution and the growth of capitalist states is being replayed in China as we speak, with a cast of 1.3 billion human beings. And if 200 years of Western economic development is being re-enacted, can we not suspect something similar on the level of the arts? In the West radical socio-economic changes produced Balzac, Zola, Dickens, Stendhal, Frank Norris, Sinclair Lewis, Dos Passos….Will modern China not have its own great voices? Does it not have them already? Those questions came to mind as I watched Ermo, with its echoes of Norris’s Greed and stories from Balzac’s Comédie humaine. Ermo is the voice of China now.

Director Zhou Xiao Wen’s film, his ninth, is set in a small cooperative village located in a northern region of dry mountain gorges. The landscape is memorable; its barrenness and harshness have the abstract beauty of stone. The village itself is all brick and stone and heavy tile roofs. People survive here by the dint of toil and an unwillingness to admit defeat in the face of either environment or bureaucracy. The old people seem content to stand aside and watch the new generation take up the struggle for which they no longer have the strength. Television is coming to the village, with its foreign soap operas and sports dubbed in Chinese. No one’s starving, but no one’s getting rich either.

Ermo is probably in her thirties, married to the older ex-chief of the village. Her husband has had some kind of severe back injury. He’s also impotent. He can no longer do demanding physical work, and the weight of supporting the family, which includes their young boy, Hizu, falls on his wife’s very capable shoulders. She doesn’t hesitate to point out her husband’s shortcomings, and isn’t much of a source for sympathy, but she keeps things together with the kind of work ethic that’s always been associated with peasant farmers. In Ermo’s case, she makes large baskets by the hundreds and hawks bundles of homemade “twisty noodles” on the streets of nearby towns.

The noodle-making is a highlight of the film. The whole process—mixing and tossing dough with one’s feet, grinding out the noodles on a heavy wooden press, hanging them in the yard like curtains—takes on the kind of gravity that Zola gave to the labour of French miners and Dickens to the workers in Hard Times.

Ermo makes a decent living for her family, but her hard work is tainted by a cold, calculating covetousness towards the fruits of her labours. Exhausted from work, she sits on her bed, spreads out the wads of small bills she’s earned, spits aggressively on her fingers, and counts and stacks. It borders on mania. That mania is more or less contained until one day, on a trip into the neighboring city, she comes face to face with a 29-inch television in a warehouse store. That TV, too expensive even for the county leader, becomes an obsession. The ultimate status symbol. Ermo had watched her own son lured away by the neighbour she despises, because the neighbour had gotten the village’s first colour TV. Now it’s Ermo’s turn. She’ll do whatever it takes to get the cash to buy that 29-inch Golden Calf.

The Mongolian (Uighur) actress who plays Ermo, Liya Ai, is flawless. Every gesture, every look, and every word ring true. Whether slaving over the noodles, haggling in the streets, lashing out in pride or anger or sheer impatience, or oxymoronically crumpling in victory, I think the last time I was so convinced by an actress’s performance was when Isabelle Huppert stunned me in Claude Chabrol’s The Story of Women.

Part of what makes Ermo so unique is her fierce naïveté. Within the small world of her own family and village, she is a tiger. Did the neighbour throw dirty water over her noodles? Fine, Ermo kills her pig in return. Is her lover secretly subsidizing her wages at the restaurant in town? As soon as she finds out she drops an ultimatum—leave your wife and marry me, now! or I’ll pay back every yuan I didn’t earn. Yet this is also the same woman who is afraid to take the sticker off the TV screen for fear that the TV might stop working, doesn’t know the difference between football and basketball, and thinks something’s gone wrong when people on the TV start speaking English. Ermo’s world barely extends beyond her village’s walls.

There’s nothing naïve about the film’s approach to Ermo’s sexuality. At first she sublimates her frustrated desires in the hard physical work of making noodles. The way she kneads the dough with her feet is more sensual than any ten minutes of naked coupling in most other movies. Her brief affair with her shrewish neighbour’s husband is borne of a powerful mixture of spite, too-longed repressed desire, and a code of honour that insists debts must be paid. When that same code of honour comes into conflict with the dictates of body and heart, however, the affair is ended as abruptly as it began.

The strength of Liya Ai’s performance also owes much to the film’s superb photography, and the uniform excellence of the supporting cast. Zhang Haiyan is the shrewish neighbour, bitter at having no sons and feeling rejected by her husband because of it. That husband, nicknamed Blindman because of his small eyes, is played by Liu Peiqui. He’s equal parts chauvinist, opportunist, rogue, and man of honour. As Ermo’s hapless husband, Zhijun Ge strikes the perfect notes as a man who’s seen better days and would love to watch the calendar roll back to the golden age when men spoke and women listened.

Some critics have labeled Ermo a comedy or a straightforward satire on capitalist consumption. It’s far more profound. This is Chinese New Wave cinema, a kindred spirit to Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows for the new millennium and the new China.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

“…when I was growing up and becoming a filmmaker I found that everybody wanted to control others’ souls, minds and spirits. Of course, it’s impossible; but year after year everyone wants to do it. The first emperor wanted to do it. He had the most power at that time. Many Chinese rulers have wanted to do this – for generation after generation. Even a wife wants to control her husband. A little kid wants to control his parent’s mind.

That is very interesting to me. So the theme [of The Emperor’s Shadow] is that nobody’s mind can be controlled.” –Xioawen Zhou, in a 1996 interview

Here’s what critic Peter Stack, of the San Francisco Chronicle, said of Ermo back in 1995:

“Ermo” is a vivacious, enthralling comedy- drama that tickles with its rustic, sometimes petty humanity. But it is also a lyrically drawn glimpse of transcendent human spirit that too often is missing from the big screen.

As you’ll see from my comments below, it’s hard to believe that we saw the same film. Perhaps it’s a glass half-filled, glass half-empty situation….If Ermo is a comedy, it’s one Samuel Beckett or Jean Genet had a hand in writing.

I still find this a powerful little film, with a memorable performance by lead actress Liya Ai. Dumping a Rousseauesque or Thoreauesque vision of life in the country as a bucolic idyll, Ermo paints a Darwinian picture of greed, one-upmanship, brutal toil, petty jealousies, and betrayals in a wind-swept and denuded landscape. This is the Chinese equivalent of the kinds of tragic tales told by Balzac and Zola. There are no winners here. The more one struggles, the harder one works, the deeper one sinks. It’s all horribly unfair. And everyone gets a share of the blame. Ermo herself thinks she can recover some of her invalid husband’s lost status by buying the biggest TV in the village. She’s willing to work herself to the bone and sell her blood by the gallon to add more paper money to the bundle she fingers and licks through every night she’s at home. Obsession is a terrible thing, a relentless downward spiral. Her husband contributes nothing to the household, either through a genuine incapacity or because the loss of his health has also meant the loss of his dignity and he’s simply given up. All he’s got left is some old cliches about luxuries being eggs and a house being a chicken. The old “Teach a man to fish….” school of wisdom. Ermo’s next door neighbor, Blindman (Peiqi Liu)–a truck driver who eventually seduces her into an adulterous affair–buys her favors on the sly until she discovers that she’s become a kept woman without her knowledge. Like so many classic adulterers, Blindman promises to leave his wife but is far too much of a coward to actually follow through. Blindman’s wife (Haiyan Zhang) resents Ermo’s careless sensuality and the fact that Ermo has the son that she’s been unable to give her husband. Cooped up in the small confines of a remote mountain village, all these characters find it impossible to distance their lives from one another. Drama is everywhere. Aside from a donkey, no one dies in this film. But another fatality, and it’s a terrible one, is hope. The last shot of the film, with Ermo’s family alone with their color TV, in an otherwise empty house, with the bleakest of winters clamped down outside, is unforgettable.

Visually, the film is impressive. The night shots of Ermo preparing noodles and kneading dough with her feet (a singular skill that puts Italian wine-stomping to shame), the shots of the battle-scarred truck winding its way down sterile-looking mountain roads, and all of the perfectly composed interiors lead one to expect great things from director Xiaowen Zhou and cinematographer Gengxin Lu. There’s an extraordinary scene near the middle of the film where Ermo sits in front of a broken mirror, and the reflection in the mirror is the picture of her broken soul. I think this is the moment we know that she is truly lost.

A film as good as this deserves a better fate than existence as a bootleg copy on YouTube and a VHS tape on Amazon.com. None of the work of either Xiaowen Zhou or Alia Liu seems to be available on the Criterion Channel.

Director Xiaowen Zhou made four feature films after Ermo, and had done a half a dozen prior. Born in Beijing in 1954, his last film appears to be Bai He, released in 2011. According to the very brief entry for Zhou in Wikipedia, many of his films were censored by the Chinese government and never shown in the West. There’s no explanation of why he stopped making films. The same article identifies him as part of the “Fifth Generation” of Chinese filmmakers, who had graduated from the Beijing Film Academy in 1982. Other Fifth Generation directors include Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige. There does appear to be a good, English-subtitled copy of a later Xioawen Zhou film, The Emperor’s Shadow (1996), on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bq4agP8vOis.

Ermo was the second feature of only six credited to Cinematographer Gengxin Lü. The last was in 2005.

Actress Liya Ai has 31 credits on Imdb. Her latest film was released in 2022. Ermo was her third film. She picked up several “Best Actress” awards for her work on Ermo and Genghis Khan (1998)

Here is a further extract from Augusta Palmer’s 1996 interview with Xiaowen Zhou, featured on IndieWire:

iW: Did you write the script for “Ermo,” too?

Zhou: Actually I did write it, but the screen credit went to someone else. It’s an interesting story. I had a friend, a person from Beijing who said, “If you want to make ‘Ermo,’ I’ll give you the money.” This guy’s name is Lang Yun. Halfway through the shooting he said he didn’t have any more money. I asked him what we should do about it and he said,

“Just forget about it.” He’s a good man but he’s very irresponsible. So I said, “You already gave me so much money and you even borrowed some of it from your friends, what should we do about that?” And he said, “That’s okay, it’s just my bad luck.” So then I had to start borrowing money myself. The worst was the time when I asked someone for money and he said he only had one yuan (about $10 US) and asked if I still wanted it. And I had to say yes.

When the film was almost finished, I met Jimmy Tan [of Hong Kong’s Ocean Films]. At that time he really wanted to make films, but he didn’t know anyone in the industry. After he met me, he said he wanted to invest in filmmaking. So I said, “Why don’t you look at this film I just finished?” I said I had a lot of loans and no way to repay them. He loved the film, so he repaid my debts and became the producer.

But Lang Yun, the first producer was unhappy. He said, “I gave you half of the money, how come I’m not getting a producer’s credit?” Because he gave up the project voluntarily, Jimmy Tan didn’t want to give him the producer’s credit. So I gave him the screenwriting credit to show my gratitude to him. But Jimmy Tan actually gave Lang Yun’s money back to him. If Jimmy Tan were a stingy businessman, he wouldn’t have felt he had to give the money back.

iW: Are you excited about [The Emperor’s Shadow]’s U.S. release?

Zhou: I’m very grateful to Fox Lorber for doing it. It’s quite meaningful to me that they are willing to release my film because even if it’s only a small percentage of the American audience, it’s still a lot of people.

Also, we all know that Hollywood films take up over 80% of the world market. Even so, we still have more than 10% of the world’s audiences. I don’t think there is such a thing as a “good’ or “bad” film. Regardless of whether it’s a commercial film or an independent, personal film like mine, it’s simply a matter of whether you like it or not. Therefore, I only consider my films finished after they’ve been seen by an audience. When I complete my work on a film, I think it’s only half done.

If there are a thousand people in the audience, there are a thousand different “Emperor’s Shadows.” I don’t want to force my opinions on the audience. I don’t want to use films to educate people. That is the attitude I hate the most. It’s like deciding who is more stupid than you are. Everybody is the same.

iW: So you don’t think there is really a difference between Hollywood and independent films?

Zhou: Of course there are differences. And I don’t think they should be called Hollywood films, since that style has been copied by many people all over the world. We should just call them mainstream films. The biggest difference between mainstream films and independent films is that the makers of mainstream films must always consider pleasing the audience first. They have to consider whether the audience will like it for the story, the characters, the dialogue. Every sentence has to be considered this way. This isn’t right or wrong; it’s just the way they have to do it.

I think I belong to the smaller group of filmmakers working on more personal independent films. My intention is to find my own feelings in the story. That’s the most important thing. After I get the financing, of course, I’ll sit down with the producer and other staff members to discuss what the audience expectations are. During that time we might have to alter our script a bit. But once the film starts shooting, then I go back to my own feelings. At that time, your eyes are no longer on the audience’s pocket. And that’s the main difference between mainstream and non-mainstream films. Of course there are other differences. The budget is much higher for mainstream films. The technology is much more advanced. The stories are similar to ones used before. They must use big stars. Non-mainstream films are just the opposite. . .

iW: But you have some pretty big stars in “The Emperor’s Shadow”. . .

Zhou: (laughs) Yeah. . . So this film is really a contradiction. In comparison with “Ermo,” this is a more mainstream film. It had such a big budget that the producer would prefer to use bigger stars. So, I prefer making lower budget films.

iW: So using big stars was the producer’s choice? Or would you have chosen the same actors yourself?

Zhou: Actually, this case is not typical. I really felt myself that Jiang Wen and Ge You were the best choices for the roles. And these two happen to be the best actors in China and the two most expensive actors.

But Jimmy Tan said, “That’s fine; I’ll pay for it.” So all the problems were solved. . .

Available on YouTube?

Yes, with Spanish subtitles at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cAc7sMiNGYY&t=236s