Conversation overheard in a Chinese barbershop, between a private dick and a Chinese fence. The fence opens:

“Yes?”

“Fei tsui jade.”

“No, I no got. I want.”

“Everybody want.”

“Who got?”

“Only big collector got.”

“Who?”

“Grail.”

“Baxter Wilson Grail?”

“He got.”

“Thanks.”

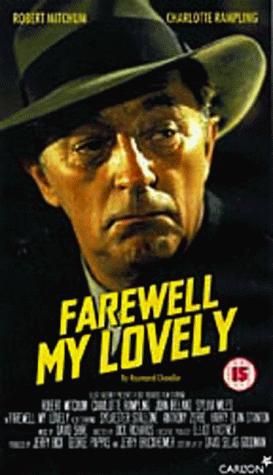

On the Richter scale of hard-boiled detective dialogue, the above exchange, taken from Dick Powell’s 1975 version of Raymond Chandler’s classic Farewell, My Lovely registers about 9.0. Any more hard-boiled, and only the punctuation marks would be left.

There are only two private eyes in the world capable of getting away with that kind of dialogue—Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade and Chandler’s Philip Marlowe. Sam Spade had his day in John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941). Marlowe almost had his day in Howard Hawks’ The Big Sleep (1946). Almost.

Humphrey Bogart, who played the lead role in both films, was the perfect Sam Spade. A man without illusions. The man who winds up holding the winning hand no matter how dirty the game. The man who puts the nails in the coffins, tosses on the dirt, says a few words and walks away from it all. Like a knife wiped clean. Mike Hammer’s soul brother.

Philip Marlowe was never that lucky. The mean streets down which he walks all leave their marks on him. Everyone he meets seems to be on a downbound train. Marlowe’s a wise-cracking knight in not-so-shining armour who can’t find a Holy Grail that doesn’t turn to s**t in his hands. Bogart and Hawks went wide of the mark. In Farewell, My Lovely, Robert Mitchum finally gave Philip Marlowe his definitive interpretation. Somebody please give this man the lifetime achievement award he deserves.

It’s only fitting that Robert Mitchum should have the last word on Marlowe. Mitchum’s name is linked to some of the high points of film noir—Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past, Charles Laughton’s Night of the Hunter, Peter Yates’ The Friends of Eddie Coyle, and Sydney Pollack’s The Yakuza. Mitchum brings to Marlowe a soulful world-weariness, saddling him with the full weight of every cheap betrayal and failed dream that crosses his path. Mitchum reads Marlowe’s lines like Dylan Thomas reads his poems. A fitting tribute to Chandler, who once wrote “I have more love for our superb language than I could ever possibly express” and who worked hard to turn pulp fiction into a poor man’s Eugene O’Neill.

In Farewell, My Lovely, the saddest thing is a lovesick gorilla named Moose Malloy (Jack O’Halloran) whose suicidal wish is to find his Velma. It doesn’t matter that she hasn’t written him once in the seven years he’s been in prison. There’s gotta be an explanation, right?

Of course, Mitchum and O’Halloran don’t go it alone. The spot-on supporting cast includes Charlotte Rampling, Sylvia Miles, Harry Dean Stanton, and John Ireland. Production Designer Dean Tavoularis and Set Decorator Bob Nelson combine to create a seedy period L.A. landscape poisoned by flashing neon signs. Detail is microscopic, from the veneers on old wooden furniture to the cheap calendars on the walls. David Shire’s score is cigarette smoke drifting down the alleys.

From the moment Moose Malloy’s dark shadow falls across Philip Marlowe’s chop suey, Raymond Chandler’s world comes to life as it never has before, and may never again.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

I still love the understated, self-deprecating humour in Raymond Chandler’s work, and his outrageous metaphors and similes. The style makes me smile. One of the best things about Dick Richard’s version of Farewell, My Lovely is how faithfully the screenwriter has held onto Chandler’s laconic prose. Robert Mitchum is the perfect actor to deliver it

It strikes me now that the visual look of the film (the production designer was Dean Tavoularis) was about as close as the movies have gotten to Edward Hopper’s paintings and the paperback art of James Avati. There’s nothing better than that opening shot when we’re looking up at Marlowe through the neon-lit window of a cheap brownstone, with a sax moaning and that voice-over that makes Tom Waits sound upbeat. The cars all roll through the streets like tanks.

Philip Marlowe remains for me the quintessential private eye—the knight in tarnished armour who’s more of a survivor than a saviour. People tend to die under his watch, and Marlowe spends a whole lot of time on the wrong end of fists, saps, gun butts, and needles.

Something that surprised me in going back to Chandler’s books in the past year is a hard edge that I’d missed the first time around. This is not a world that takes kindly to gays, union leaders, or communists. In some distinctly unpleasant ways, Raymond Chandler was a man of his times. The movie versions of his novels have largely done him the favour of leaving out bits that would, in this day and age, make Marlowe sound like a jerk.

Watch for Sylvester Stallone in an early screen appearance.

A few lines from Chandler’s novel:

“He spread his yellow hands sadly. His smile was cunning as a broken mousetrap.”

“The woman’s eyes became fixed in an incredulous stare. Then suspicion climbed all over her face, like a kitten, but no so playfully…..She simpered. She was as cute as a washtub….Thick cunning played on her face, had no fun there and went somewhere else….A lovely old woman. I liked being with her. I liked getting her drunk for my own sordid purposes. I was a swell guy. I enjoyed being me.”

“The voice grew icicles. ‘I should not have called you if it were not [legitimate].’ A Harvard boy. Nice use of the subjunctive mood. The end of my foot itched, but my bank account was still trying to crawl under a duck. I put honey in my voice and said: ‘Many thanks for calling me, Mr. Marriott. I’ll be there.’”

“It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained glass window.”

“The coffee shop smell was strong enough to build a garage on.”

“I looked at my watch once more. It was more than time for lunch. My stomach burned from the last drink. I wasn’t hungry. I lit a cigarette. It tasted like a plumber’s handkerchief.”