Let’s begin by confusing the issue. This is a movie review, so I’ll talk about books for a while. Trust me. You’ve probably seen copies of the standard movie review anthologies—Leonard Maltin’s Movie and Video Guide, Martin & Porter’s Video Movie Guide, Roger Ebert’s Movie Home Companion–at your local bookstores. All three are useful, and Ebert’s in-depth reviews should be required reading for anyone who loves movies. Life, however, is incomplete without its guilty pleasures. Like cheesecake. Now, the chocolate cheesecake of movie review anthologies has got to be VideoHound’s Golden Movie Retriever and its mini-commentaries on 22,000 sublime, incomprehensible, insupportable, mundane, dubious, or outrageous motion pictures. From Zhang Yimou’s 1987 Chinese classic Red Sorghum to Red Skelton’s Funny Faces 3, from Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window to La Sombra del Murcielago (“Monsters and Mexican wrestlers fight over a woman. In Spanish.”), the Retriever is a dangerous book to leave on the bathroom shelf (provided that you have a bathroom shelf big enough to hold it). Making the book even more of a guilty pleasure is an extensive Category Index listing pictures with related plots: Mad Scientist movies, Yuppie Nightmare movies, Rebel With A Cause movies, Rebel Without a Cause movies, etc. I’ve no bones to pick (pun intended) with the Hound’s 350 chosen categories; it’s just that they missed one—Movies That Treat Their Protagonist With Unspeakable Cruelty.

David Mamet’s Homicide (1991) belongs in Category 351. I haven’t seen a good film hurt its main character so badly since Peter Yates took Robert Mitchum for a hard fall in The Friends of Eddie Coyle. If you thought King Lear had a rough time of it, try walking a mile in Detective Robert Gold’s shoes. A top hostage negotiator for the Baltimore police department, with 22 citations for valour, Gold (Joe Mantegna) seems to have done everything right for his whole life except to find a meaning for it. He’s always been “first through the door” in a violent standoff–because of how little he ultmately values his own life. He’s a good negotiator–because he himself feels trapped. When a middle-aged man in a lock-up suddenly goes berserk and slashes him across the head with his own gun, Gold is angry not at the pain or the act, but at the fact that once again the universe seems to have randomly singled him out as the patsy.

Gold’s lapsed Jewish heritage doesn’t help matters. Prejudice against Jews within the police force has warped his career. Thinking he is alone on the telephone in the opulent library of the home of an elderly Jewish woman whose murder he is investigating, he indulges in his own bitter anti-Semitic diatribe: “These are not my people, baby…so much anti-Semitism the last 400 years we must be doing something to bring it about.” The woman’s granddaughter overhears him, and when she asks “Do you hate yourself that much? Do you belong nowhere?” he cannot respond. Near the end of the movie, the black fugitive he’s hunting asks him much the same question. His answer is almost, but not quite, the cruellest moment in the film.

Aside from his partner, Tim Sullivan (William H. Macy), with whom he engages in some easy banter that’s Homicide‘s best dialogue, everyone Gold meets seems bent on cutting out the hollow centre of his soul with both the keenest and bluntest instruments possible. The murdered woman’s son, a wealthy Jewish doctor, tells him: “We’re always making it [anti-Semitic conspiracies] up—is that right? It’s always a fantasy, isn’t it?” A black government official dismisses him contemptuously as a “little kike,” while members of a militant Jewish self-defence society reject him as a coward with no loyalty to his own people. His own superior officer buckles to pressure from above and pulls him off a case he is instrumental in breaking wide open. Gold’s not even safe in a library. As he stands there waiting for some information, a young Hassidic student lectures him on the comparative symbology of the star on his detective’s badge and the mystical Star of David (something about “the impossibility of deconstructing pentagrams”), walking sadly away when he realizes Gold cannot read Hebrew.

With every step Gold takes, Mamet collapses his world further in upon itself. Paranoia turns into genuine conspiracy, and conspiracy turns back into illusion. Every act of loyalty is an act of betrayal. Neither victims nor killers are who they should be. Smiling grandmothers pose in old photographs lovingly cradling Thompson machine guns. As with any tragic figure (and Homicide is such a fine film because its protagonist is a tragic hero), Gold’s only defence against the Furies is ignorance of their existence. Once he starts to see them, he’s doomed. Gold’s partner tries in vain to keep their life-saving, ironic distance intact (“You’re better than an aquarium. There’s something happening with you every minute.”). It’s too late.

Where Gold’s going, even your own mother turns you in. The simplest things you leave undone undo you.

Finally, listen for the silences in this film. They counterpoint the violence of action and language. Alaric Jans’ minimalist musical score (solo piano much of the time), plays softly against backdrops of urban decay, deserted rooftops, tenement halls, and moneyed salons. Music, cinematography, decor fuse. I loved the tone of this movie. And because I can’t think of where else to mention it, I also loved Mary Jefferson’s embittered portrayal of a ghetto mother standing by her son. By the way, you probably want to know The Meaning of It All. In Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy it was 49. In Homicide, it’s pigeon feed. That’s right. Pigeon feed.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

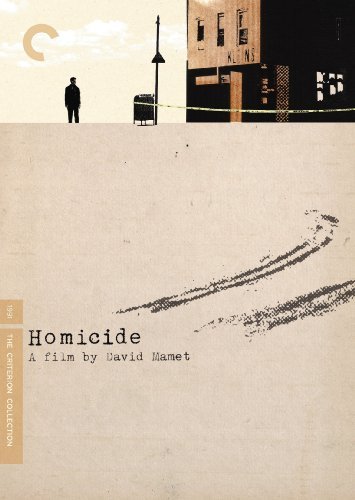

[Homicide is now out as a Criterion disk, which means no easy access unless you shell out big bucks or can access Filmstruck streaming services. I’ll get a hold of a copy eventually, but have struck out here for the moment.]