I’ve said it before. Who needs special effects when you’ve got the real world? Nothing is more spectacular than the natural world we’re born into, or more spectacularly deranged than the artificial one modem technology births round us. The special effects wizards at California’s Industrial Light & Magic company might do a wonderful job on Steven Spielberg productions, but stick a time-lapse camera in Mother Nature’s hands and she’ll turn your head around. Clouds pouring over mountaintops like rivers in spate; volcanic landscapes like levels of Dante’s hell; the camera’s eye in vertiginous flight through canyon & floodplain. Cinematic ballet with stones, winds, sunlight and shadow. National Geographic meets Tchaikovsky. The Gaian Suite.

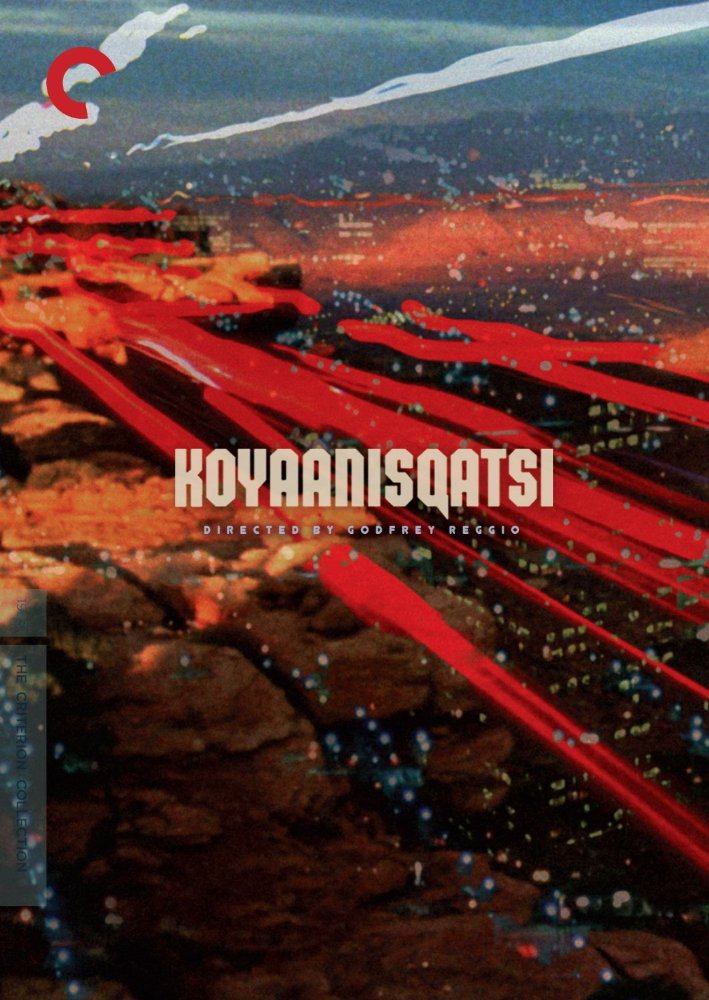

If Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (1983) ended at the half-hour mark, the above paragraph would just about take care of this month’s review. I could switch my computer off and go back to watching Mae West trying to seduce Cary Grant. Life should be so simple. Koyaanisqatsi ends at the 87-minute mark. The first, mesmeric half hour is merely the prelude to a furiously accelerating journey from the pristine into the profane. Arroyo to barrio. Mesa to mall. Strap Tchaikovsky to the front of the Coney Island roller coaster, stick a camera in his lap, and let’im ride. Get rid of the swans and bring on the nutcrackers and the robot welders. The brand! new! Ballet Méchanique! Automobile headlights flow through urban fibre optjc seas; commuters pour down Niagaras of escalators. Assembly line inspectors grab Twinkies and defective wieners like bears swatting trout out of streams. And just one word describes it all.

Koyaanisqatsi.

For once it’s not the Greeks who had the word for it. The title of Reggio’s film comes from the language of the Hopi Indians of southern Arizona:

ko-yaa-nis-qatsi, n. 1. crazy life. 2. life in turmoil. 3. life out of balance. 4. life disintegrating. 5. a state of life that calls for another way of living.

That definition, along with three short Hopi prophecies, constitutes the entire text of the film. Perhaps even the prophesies are superfluous text. Crazy life. A state of life that calls for another way of living. I mean, what other conclusion can one come to after realizing that, from far enough away, L.A. looks exactly like a printed circuit board? Charlie Chaplin may have been funnier in Modern Times (1936), and both Brazil (1985) and Blade Runner (1982) may have shown us even more dismaying futures, but in Koyaanisqatsi director Reggio, photographer Ron Fricke, editor Alan Walpole, and avant-garde composer Philip Glass combined their talents to produce a unique indictment of Now. Along with opening and closing images of awesome stillness and disintegration, we are even given a glimpse at the Judges who may be around for the Final Verdict. As they say on the X-Files, The Truth is Out There.

Koyaanisqatsi’s the kind of cinema experience first envisioned by the great Russian director Sergei Eisenstein seventy years ago. Music + montage = Message. No screenwriters need apply. In one of the finest books ever written on the art of motion pictures, Film Form, Eisenstein said:

“The film’s job is to make the audience ‘help itself,’ not to ‘entertain’ it. To grip, not to amuse. To furnish the audience with cartridges, not to dissipate the energies that it brought into the theater….”

“On a certain level our [Russian] cinema has known…a severe responsibility for each shot, admitting it into a montage sequence with as much care as a line of poetry is admitted into a poem, or each musical atom is admitted into the movement of a fugue.”

That comparison with a fugue brings us to Philip Glass’s role. Although better known for three revolutionary operas- –Akhnaten, Satyagrapha, and Einstein on the Beach (an opera even stranger than its title)—Glass has occasionally contributed his talents to films as diverse as Hamburger Hill, Mishima, and The Thin Blue Line. With the exception of some eerie choral chanting in Hopi, most of the music for Koyaanisqatsi is performed on a classic church organ. The score ranges from magisterial to shrill. The match of sound to image is superb. Although useless at parties, if your music collection includes a lot of Stravinsky and Erik Satie you’ll probably want the soundtrack.

Arresting as it is, Koyaanisqatsi does overlook one important thing in its single-minded drive to put North American life in perspective. It has something to do with old Tchaikovsky on the rollercoaster.

You see, roller coasters are FUN. Lots and lots of fun. The bigger they are, the more fun they are.

New York and L.A. are very, VERY big roller coasters.

Does anyone want to get off???

Or do we just keep building them bigger and selling more tickets?

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

I really don’t want to add a lot of words to describe what I still feels is a stunning visual/aural experience. I now seem to be less concerned with a message in the film than I am with its aesthetics. What you’ll see and hear will change every time you watch this film. I’d like to point out that in the time since Koyaanisqatsi was released, photographers Sebastião Selgado and Edward Burtynsky have created an extraordinary body of work that complements that of Godfrey Reggio. Manufactured Landscapes, listed above, is a documentary on Burtynsky’s photographic mission.

In a short documentary included with my copy of Koyaanisqatsi, Reggio says that his goal in making the film was to capture what it is like for humanity to live inside technology, as opposed to living with it. We don’t use technology, we live it. It was an extraordinarily prescient statement, formulated as it was just before the explosion of computer-based technologies went from home machines with cassette tape data storage to Macs, iPods, virtual reality, smart phones, GPS, steaming video, and driverless cars. We’re now living inside a technological web light-years beyond anything that Reggio could have imagined in 1982. I doubt that today’s special effects wizards can come up with architecture that’s much more mind-blowing than the actual buildings one finds when googling something like “world’s coolest buildings.” What can be conceived, it seems, can be constructed.

Another of Reggio’s comments which struck me was has reference to his desire to “ennoble with portraiture.” The human faces in the film struck me more forcefully than ever on my latest viewing. Particularly, it’s the way he holds those faces onscreen for longer than you’d expect. We don’t know anything about these people; it’s impossible to judge them. They could be wonderful human beings, or monsters . It’s like looking at the 19th century portraits of Jean-August-Dominique Ingres—the paintings are magnificent, but one can’t help suspecting that some of the subjects were more Dorian Gray than Jean Vanier.

The idea of showing rather than polemicizing underlines the entire film. This is what our modern world looks like; it’s up to the viewer to come to his or her own terms with it, to celebrate it or to despair. Reggio insists that he’s offering experience rather than information. Again in his own words, the paradoxical “beauty of the shiny beast.” His spiritual vision is marked by his extensive work with the Catholic Christian Brotherhood, a part of his biography that needs to be taken into account in approaching his work. Here’s an excerpt from a portrait of Reggio by John Patterson, published in The Guardian, March 27th, 2014:

“I went to a Catholic school, very Catholic family. We model ourselves after the adults we admire, and when I met these men, these brothers, I saw how generous, how joyful, how convivial, how unattached but full of life they were and I thought: gee whiz, maybe I could do that. Little did I know what I was getting into – we all do the right things for the wrong reasons. So at 13 I decided to leave home, at 14 my parents let me, and I never returned. Instead, I returned to the middle ages, and the brotherhood made the Marine Corps look like the Cub Scouts. I became a young zealous monk. My Che Guevara was Pope John XXIII, a pope who never wanted to be pope, and just a guy that moved me to the quick. He said, accept nothing, challenge everything, even the structure of the church. These were marching orders for a young monk, but the institution I was a part of had become deadened.”

After a decade of social work and community organising in the barrios of New Mexico, and feeling that his and the brotherhood’s aims were out of kilter, Reggio joined the mass post-60s exodus from the church of young Catholic idealists who had hoped for more substantial and meaningful reforms from the second Vatican council.

And suddenly he was a film-maker? “As a brother you don’t see movies, because although you’re in the world, you’re not of it. But another brother showed me a film and said it might change my life, Los Olvidados by Luis Bunuel. Nothing to do with entertainment, but it went right to my soul, I’ve never had an experience like that. I bought a copy and showed it around and the movie became our church, it had a tremendous impact on the street gang kids who saw it.” Alongside Bunuel, he acknowledges one mentor, friend and genius, the Armenian docu-poet Artavazd Peleshyan (The Seasons of the Year): “If fire is the medium, I make sparks, he makes lightning bolts.”

I loved Philip Glass’s comment that they could take their time making the film (several years), because “no one was waiting for this movie.” Sometimes it’s great to be out of the mainstream.

Godrey Reggio’s recommended reading list for the film includes Jacques Ellul, Ivan Illich, David Monangye, Guy Debord, and Leopold Kohr.

It’s my goal in the next month or so to check out the three Reggio films that followed up on Koyaanisqatsi. I’ve been sadly remiss in doing so. All are readily available through sources such as iTunes. I’ll end up either writing further reviews of his more recent films, or just adding to this one.

Note: I’ve always watched Koyaanisqatsi on a large screen, never on television. Go for the biggest surface you can find. With this one, size matters.