https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mwx0X4tAXn4&t=28s

The sword of anxiety cuts into our skin

God have mercy—deliver us from our trials.

–from a gypsy song

Until I was in my late twenties, I don’t think I really believed in gypsies. Gypsies were romantic inventions, like swashbuckling pirates with cutlasses and parrots on their shoulders. The only gypsies I knew were in folk songs and operas and thick novels by Victor Hugo. All that changed when I moved to Europe. Suddenly, I was driving past gypsy caravans parked in fields outside French cities; I was watching ten-year-old girls in light, flowered dresses stealing wallets in the Paris Metro; I was living in a neighborhood where gypsy beggars put in long days “on the job” like steelworkers punching time clocks. Django Reinhardt’s music was everywhere. An early-morning stroll through the industrial wastelands along the Seine in the north of Paris took me (nervously) through a bivouac of sleeping men, women, children, dogs.

And, of course, I saw my first movie about modern gypsy life.

It was a 1967 film by Yugoslavian director Alexandre Petrovic, called J’ai même rencontré des Tziganes heureux (I’ve even met some happy Gypsies). The winner of the Jury prize at Cannes that year, Petrovic’s film—particularly the bitter irony of its title—rang true with everything I was glimpsing of a life at odds with the cultural ideals of the West: stability, wealth, ambition, the rule of law. As much as a rebellious French child might have wanted to run away with the circus, she or he might have dreamed of the outlaw mystique of a gypsy life. How fitting that one of the first movies ever made, an 1896 short by the extraordinary French magician-turned-filmmaker Georges Méliès, was The Camp of the Bohemians.

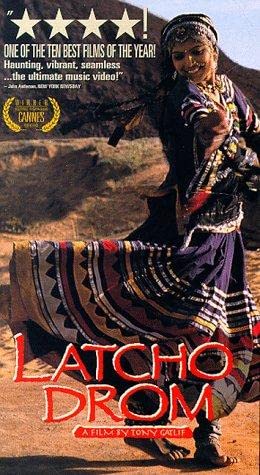

If I were ever to find a copy of Petrovic’s film, I’d buy it for our local video store. It’s haunted me for twenty years. In the meantime, this month’s column is about another, very different portrait of the Rom (the name now most commonly used for the Gypsy people) that is available in Crawford Bay. Perhaps more of an extended music video than a traditional film, Tony Gatlif’s Latcho Drom (“Safe Journey” in the Romany language) is one of a series of films about Romany history and culture this director has made over the last thirty years. Gatlif was born in Algeria in 1948, his parents of French and Gypsy descent. Music is the sublime thread through all of Tony Gatlif’s gypsy films, from Les Princes (1983), through Latcho Drom (1993), Gadjo dilo (1997), Vengo (2000) and Swing (2002), but it finds its purest form in Latcho Drom.

The focus on music is the film’s great strength, and its weakness. I’ll not dwell on the latter. Latcho Drom will teach you little of the harshness, intensity, challenges, and dangers of vagabond life on society’s margins. Gatlif’s other films address those issues directly. With Latcho Drom the director wanted to paint an aural/visual tapestry of Romany music from the deserts of Rajasthan in India to the towns of Andalusia in Spain, passing through Egypt, Turkey, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, and France. The journey crosses a thousand years in time, and parallels the original migration of the Rom from India across central and western Europe. Because the film has no narration, other than translations of some of the songs, a bit of a road map doesn’t hurt. This review is one, but I’d also recommend Bart McDowell’s fine National Geographic volume, Gypsies: Wanderers of the World (it traces the precise route of Gatlif’s camera, in reverse), and the French website for the journal Etudes Tsiganes (www.etudestsiganes.asso.fr/).

Latcho Drom begins with a small troop of Rom migrating across Rajasthan. The men ride in two-wheeled carts drawn by oxen, while the women and children walk behind. A young boy sings a song of homelessness and longing (“I will burn my horoscope that exiled me so far from those I love. I want to return to my family and run barefoot.”). His voice is pure and beautiful, and his presence links together the stages in the film’s journey. One clear message is that Romany tradition remains strong because it is taught to the children. Women and girls dress in the remarkable clothes and jewelry of desert women of this part of the world, and at twilight they dance to the music of one of the many unique gypsy orchestras we meet on the journey. The ceremonies are unfathomable to the outsider. The musical instruments we listen to are exotic, like a couple of the ones we were fortunate enough to hear at this year’s Starbelly Jam music festival.

In Constantinople the music of Latcho Drom becomes the music of the belly dance (with, interestingly, no bellies showing but much wonderful hip-shaking) and love songs with titles like “Dora Dora” and lyrics like “the fire that burns inside me drives me crazy.” Some things are universal.

Although Latcho Drom has the look of a documentary, the scenes are carefully staged. There is an interesting tension between the authenticity of the music, musicians and dancers, and the artifice of the cinematography. But that cinematography is gorgeous, and this is a film of things loved rather than things dissected. I particularly admired the faces in this film; Rembrandt might have painted them this way had he grown up with the light of the Orient.

There are somber moments. Landowners carrying shotguns telling a band of gypsies to move on. Workers bricking up the doors and windows of abandoned buildings to seal out gypsy squatters. In Rumania a gypsy song laments persecution under the Ceausescu dictatorship. Monolithic state architecture now stands seemingly empty and brooding, concrete ghosts of Orwell’s 1984. In Germany, as the camera pans across a winter landscape of snow, frozen rivers and barbed wire, the song is of the Holocaust and Hitler’s hatred of the Rom. The singer has the numbered tattoo of an Auschwitz survivor on her arm. Tony Gatlif was one of the first filmmakers to explore this lesser-known genocide.

But Latcho Drom is a film about music and life, not death. The Hungarian language actually has special words for being entertained by Gypsy musicians. It’s easy to see why. An old man plays an odd tune on his violin with a single string from his bow. A black stallion gallops through the fields to a soundtrack of hammered dulcimers. A band of gypsies brings a smile to the face of a heartbroken woman waiting for a train. Other Romany set up camps in treetops—a vision out of Tolkien or Dante. In Spain, it’s the grandparents’ flamenco. And at Saintes Maries de la Mer in the south of France–where Saint Mary Jacobe and Saint Marie Salome, the mothers of Saints John and James, are said to have landed in a small boat–some incredible guitarists play in a 12th century crypt for a statue of Sara-la-Kali, Sarah the Black, the servant girl who served the two Marys and who is the patron saint of the gypsies.

At the end of the festival of Saintes Maries de la Mer, the statues of the two Marys are carried into the Mediterranean to music and shouts of “Vivent les Saintes Maries!” from the single biggest crowd of Rom to gather anywhere. Latcho Drom gives the rest of us a taste of what they’re celebrating.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

This is the most joyful celebration of music as a communal activity that I have ever seen. One writer described the Rom as “natural performers and intense spectators,” and that’s who we see in Latcho Drom. Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz comes close, but it’s a celebration in a very specific place & time, and for an adult audience. Latcho Drom ranges across three continents and embraces men, women, and children from India, Egypt, Turkey, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, France, and Spain. The Band certainly knew something about music and life on the road, but for the Rom life is the road and music is life. And it’s not just the soundscape of Tony Gatlif’s film that is splendid; so, too, are the landscapes of cinnamon-colored deserts, endless country roads, magnificent trees, remarkable faces, handsome horses, unfamiliar cities, unique musical instruments, and distinctive caravan camps. Latcho Drom gives every viewer a chance to share in wonder. What a gift he’s given us! I’m curious to know how Gatlif gained the trust of so many who might otherwise have been reluctant to share their private worlds with the camera’s eye. Their trust & candor is a small miracle in itself. The film’s narrative reminded me of an older National Geographic book, Gypsies: Wanders of the World. The author of that book, Bart McDowell, retraced the 13,000-mile migration of the Rom from India to England in the company of an English Rom, Clifford Lee, and his family. I was also reminded of Paul Salopek’s Out of Eden walk, a 24,000-mile embrace of humanity as generous and grounded as Gatlif’s embrace of Rom culture across continents.

Although Latcho Drom has one heart-breaking segment where barbed wire, snowy fields, and a powerful lament recall the tragedy of Nazi genocide of the Rom, this is not a film about the harsher sides of Rom life–persecution, family feuds, poverty, exile, violence. These stories are told elsewhere: in novels by Romani writers such as Mateo Maximoff, in films such as Aleksandar Petrovic’s I Even Met Happy Gypsies (1964), and in publications such as Romani Studies (2000 to now) and The Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society (1888-1999, available free online at HathiTrust.org). Here’s more info about the Journal:

Digitized copies of the Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society, 1888-1999, are now available at http://www.hathitrust.org. A catalog, or bibliographic, search, and an experimental full-text search both cover these issues of the Journal. The Journal issues are scanned from copies at the University of Michigan, Indiana University, University of California, and Princeton University.

To access the Journal, go to the HathiTrust web site. There is no need to log in. The Gypsy Lore Society has created a Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society collection within the HathiTrust Digital Library. You can search the collection independently of the rest of the repository. To use the collection, go to the HathiTrust home page and click on “collections” on the top menu. In “find a collection” enter “Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society.” Enter your search term in “search in this collection.” Select a result; the search term should appear in “search in this text.”

The Wikipedia article on Latcho Drom provides a fine summary of what’s happening in each of the film’s different locations:

The film contains very little dialogue and captions; only what is required to grasp the essential meaning of a song or conversation is translated. The film begins in the Thar Desert in Northern India and ends in Spain, passing through Egypt, Turkey, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, and France. All of the Romani portrayed are actual members of the Romani community.

- India—Kalbelia people gathering in celebration.

- Egypt—Ghawazi people sing and dance while children observe and begin to learn the artistic traditions.

- Turkey—Turkish Roma in Istanbul sell flowers and play their music in cafes while their children observe and learn.

- Romania—A young boy listens to Roma musicians sing about the horrors of Nicolae Ceausescu and his reign before returning to his village, where the musicians from earlier begin a semi-spontaneous and joyous music session.

- Hungary—A Roma family on the train sing of their rejection by non-Romani people. The scene cuts to the train station ahead, where the waiting family set up a fire as they wait across the tracks from the train station while a Hungarian woman and her young son wait on a bench. The boy, seeing that his mother is sad and cold, ventures over to the Roma, who strike up the music and cheer the woman up before their family on the train arrive and they walk away singing.

- Slovakia—The train screeches along a barbed wire fence as an old woman sings a song about Auschwitz and the camera pans down to reveal her imprisonment tattoo from her time in the concentration camp. A series of shots show a winter camp before the occupants return to the road.

- France—French Romani set up camp with their metal vardos in a summer field and briefly go about their business, making baskets and other crafts before being driven off by landlords. They leave behind clues that a fellow Romani musician Tchavolo Schmitt uses to find them. They all meet up for the celebration in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer and celebrate the festival of Saint Sarah, patron saint of the Romani.

- Spain—Latcho Drom closes in Spain, showing flamenco puro performed by local “Gitanos”. The famous “gitana” singer La Caita sings mournfully of the centuries of persecution, repeatedly imploring “Why does your mouth spit on me?” as her query echoes out over the town.

-

The use of music in the film is highly important. Although Latcho Drom is a documentary, there are no interviews and none of the dialogue is captioned. Few of the lyrics are captioned. The film relies on music to convey emotion and tell the story of the Romani. Musicians include the Romanian group Taraf de Haïdouks, La Caita (Spain), Remedios Amaya and gypsy jazz guitarist Tchavolo Schmitt. The soundtrack was composed by Dorado Schmitt, who appears in the film.

And check out the Wikipedia article on Romani Music here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romani_music