Hanuman [the monkey-king] closed his eyes and put his hands in his lap. “This tale is full of peril and safety,” he began. “it will armor noble souls with courage, and bring heart failure to cowards. It will perplex the wise and baffle the foolish, and make them both follow their hearts. It gives reasons for acting in every way; its chapters haunt the mind; its verses make heroes hunger for glory…Oh King of the Bears, this story is not for worried ears and weak nerves, for it holds dread and rash chivalry, sweet honor and elegant danger, and graceful bravery and bountiful generosity beyond knowing.”—from Ramayana, William Buck translation

One of the great pleasures in reading Hindu epics such as the Mahabharata or the Ramayana, whether for the first or the fifth time, is their sheer unpredictability. Things don’t happen because they are endpoints in a Cartesian chain of logic; they happen simply because they must happen at that particular place and at that particular time—and “logic” and “common sense” be damned. At one moment the hero Rama can casually annihilate fourteen thousand invincible demons that have terrorized Dandaka Forest for centuries; the next moment he loses his own wife through the simplest and most obvious of feints. When the Vindhya Hills become jealous of the Himalya Mountains and grow so high that they block the sun, moon and stars, the gods are powerless to check the usurpers. Meanwhile a tiny priest, Agastya, finding the Vindhya Hills blocking his path, politely asks them to bow low so he can pass…and they obey! Omnipotence and folly, grandeur and diminutiveness, impossibility and inevitability—odd and wonderful bedfellows.

Which bring me to the spaghetti western I want to review this month.

Odd and wonderful bedfellows, that is.

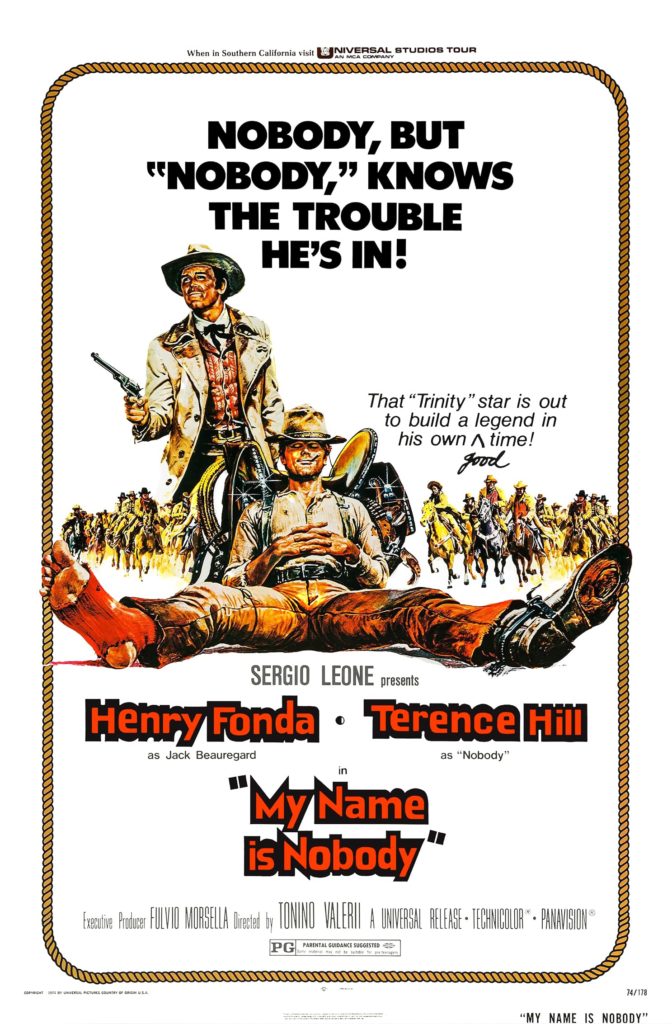

Italian director Sergio Leone made two westerns in the classic epic western mold: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly(1967); and Once Upon a Time in the West(1968). I’ve already reviewed the latter film in this column, and I’m waiting for a bigger TV before I tackle the former. But Leone also co-wrote and co-directed an off-beat western that remains one of my favourites: My Name is Nobody (1973). It’s the story of a fool and a hero and 150 demons, sort of.

The fool is a young man (Terence Hill) with no name, the “nobody special” everyone dismisses out of hand. He looks like a blue-eyed, blond-haired Minnesota farm boy, still wet behind the ears, smiling, naïve as all get-out. All “Ah, shucks!” and “Who, me?” and “Gosh, I don’t think I could do that!” It’s easy to miss the permanent twinkle in those eyes, the hint of mockery in that smile, the utter lack of fear. What the kid really has, behind the anonymity and the goofiness, is a kind of Zen imperturbability. This wise fool is a tall drink of water and a very deep well. “Nobody” is bad news for bad guys. As hulking as the Vidhya Hills, and considerably uglier, the motley crew of killers in My Name is Nobody discovers that L’il Abner is closer to Alpha & Omega.

There’s only one man Hill’s character looks up to. Like a little kid worshipping Joe DiMaggio or Babe Ruth, “Nobody” has memorized every highlight of U.S. Marshall Jack Beauregard’s career as the most feared lawman of the West. Played to perfection by Henry Fonda, in his second time working with Sergio Leone, Jack Beauregard is a man who knows that his time is up; the century is about to turn, the Wild West is morphing into something new. He knows his eyesight is failing and his draw is getting slower. If he hangs around it’ll be to either live out the rest of his life as an anachronism, or get shot down by a punk who’s younger, faster, dumber. For Beauregard, it’s time to retire, time to catch the next steamboat out of New Orleans for Margaritaville.

The young man with no name has other plans. Legends can’t just fade away. Heroes have to go out in style. “It just ain’t good for some folks to live too long.” Why would Jack Beauregard, the Jack Beauregard chose to fade from the pages of history when he could burn his way into them? All he’d have to do would be to take on—alone, of course—the last great outlaw gang, the Wild Bunch, “150 pure-bred sons-of-bitches on horseback who ride like they were thousands.” And then die. Of course.

Beauregard is understandably a bit skeptical of this “plan” for his canonization. He points out that history only makes interesting reading for those still alive to enjoy it. Whatever he’s done in the past has been for order and law, not grandstanding. He’s done what’s had to be done, evaluating the risks, minimizing them, dispensing justice dispassionately and efficiently. What kind of an idiot would suggest that he suddenly throw his life away against hopeless odds for the sake of a mere gesture? And what kind of a fool would he have to be to listen?

One man against 150?

Throw away a lifetime’s worth of careful calculation for a moment of glory and rash chivalry?

About as much chance of that happening as of a monkeyleading armies against a Demon King…….

Aside from the perfect casting of Terence Hill and Henry Fonda, My Name is Nobody would be a far less successful entertainment if the visual and aural landscapes weren’t so perfect. The whole film looks as dry and weathered and worn and authentic as an old prairie barn. It didn’t hurt that the film was shot on location in Colorado, New Mexico, Spain, and New Orleans. Kudos to the set designer, the sound technician, and the cinematographer. Nowadays many directors might spend a hundred times the money and wind up with something that looks like an amusement park in Disney World.

Another bonus: Ennio Morricone’s most tongue-in-cheek score outside of Two Mules for Sister Sara. When my wife glanced at the TV as I was watching Nobody she seemed confused that a bright little tune that Petula Clark wouldn’t have been ashamed of was playing over top of a looming gunfight. And then there are those wonderful, ominously-jangling guitar chords, as understated as heralds of the Apocalypse. And the Wild Bunch’s thundering leitmotif, described perfectly by one fan as “hoedown Valkyrie.”

The film’s violence is as off-beat as everything else about it. Hill might be fast on the draw, but he hardly ever shoots anyone. It’s entirely fitting that in a western which largely subverts traditional violence, “Nobody” should find a grave in a dusty cemetery with the name “Sam Peckinpah” on it—referring to the director whose The Wild Bunch (1969) is arguably the bloodiest western ever filmed. Some of the action sequences in Nobody could have been choreographed by Jackie Chan. In the most entertaining set-pieces, Terence Hill slaps one outlaw silly instead of shooting him, knocks down half a dozen others with the Wild West equivalent of a tether ball, and gets great mileage out of a carnival Haunted House. And need I mention the great urinal showdown? My Name is Nobody also does an end run around that classic excuse for gunplay in hundreds of westerns—revenge. “They shot my brother….” doesn’t quite pan out here.

Hey, there’s even a parable. You know, the one about the canary, the cow, the cow pie, and the fox….

Available on YouTube? Yes, in an okay copy in English with German titles:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w9Vfoa6rDkM

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

The Westerner is par excellence a man of leisure. Even when he wears the badge of a marshal or, more rarely, owns a ranch, he appears to be unemployed…We are not actually aware that he owns anything except his horse, his guns, and the one worn suit of clothing which is likely to remain unchanged all through the movie. It comes as a surprise to see him take money from his pocket or an extra shirt from his saddlebags. As a rule we do not even know where he sleeps at night and don’t think of asking. Yet it never occurs to us that he is a poor man; there is no poverty in Western movies, and really no wealth either…Possessions too are irrelevant. Employment of some kind–usually unproductive–is always open to the Westerner, but when he accepts it, it is not because he needs to make a living, much less from any idea of “getting ahead.” Where could he want to “get ahead” to? By the time we see him, he is already “there”: he can ride a horse faultlessly, keep his countenance in the face of death, and draw his gun a little faster and shoot it a little straighter than anyone he is likely to meet.

–Robert Warshow, “Movie Chronicle: The Westerner”

Before Star Trek, Star Wars, and the Marvel Comic Universe dominated the pop culture world by a self-conscious, potent combination of humor and myth-making, the same approach had been used just as effectively by the creators of the 1960s Italian spaghetti westerns. The storytelling reached epic proportions with Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966) and Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), but all of the right ingredients went into Tonino Valerii’s more modestly scaled (but still epic) My Name is Nobody. Tonino’s film has a lot going for it, starting with one of the best opening sequences in the history of the genre. The barbershop scene has the patient perfection of the train station sequence the opens Once Upon a Time in the West. Henry Fonda was one of the great western film icons, whether playing a gunfighter on the right or wrong side of the law…or somewhere in between. As Jack Beauregard in Nobody, he’s the ultimate blend of world-weariness, deadly force, nobility, and wry, self-disparaging humor. He’s the Fred Astaire of gunslingers, what Robert Warshow called “an image of personal nobility.” He’s the twilight of an entire era in one man.

Beauregard’s biggest fan is the much younger, blue-eyed, equally deadly, Cheshire-Cat-grinned Terence Hill as the film’s eponymous Nobody. He’s like a cute but potentially lethal puppy dog. Hill’s vision of Fonda single-handedly challenging the 150 thundering outlaws of the Wild Bunch is the one that all of us hero-worshippers wish for our icons. It’s the essence of a great dramatic series such as Foyle’s War, where the lead character demolishes a long string of venal, morally corrupt upper echelon bureaucrats and power-mongers, using nothing but a piercing intelligence and a few well-chosen words. The confrontation with cosmic-sized evil is also the basis for Doctor Who, in any of his incarnations. But unlike the lead actors of My Name is Nobody, who stand largely alone except for their one shared bond, Foyle and Doctor Who have companions. And there are women in their worlds, whereas the feminine presence in spaghetti westerns, with the rare exception of Claudia Cardinale in Once Upon a Time in the West, is negligible or nonexistent.

Even the landscapes of My Name is Nobody are mythical, woven together from locations in Spain, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Louisiana. Like the medieval Everyman, this is the West of all of our imaginings. A kind of Wasteland to match that of the Grail legends. Also the stuff of our imaginings are the dusty, grimy towns and ranchos and outposts and ports–for once looking like they’ve actually seen hard living instead of being hastily erected Hollywood facades. I’m not sure who was mostly responsible for Nobody’s production design, but he did a damn good job of it. The combination of “the solid surface and a high degree of abstraction” is a key to the staying power of the best Westerns, spaghetti or otherwise.

As important as the visual design of the film is its aural landscape: loudly ticking clocks, pounding hooves, barking dogs, raucous chickens, scraping razors, bird calls, creaking wooden floors, curry combs, steam engines. And weaving its way through this tapestry of sound effects is the always-anticipated masterful Ennio Morricone score, another orchestration of the unlikely, the incongruous, and the rhapsodic.

I’ve seen one film critic refer to the kind of storytelling going on in Westerns as “mythic extremism.” I’d prefer to call it “mythic enthusiasm.” As you can tell, when it comes to these films I’m pretty enthusiastic myself. I can savor the moments when Fonda pins up the tail of his jacket before a gunfight, relish the only classic urinal scene in cinema history, and smile at the mordant humor of Sam Peckinpah’s grave right there next to the Nevada Kids’.

Director Tonino Valerii died in 2016. He’d directed about a dozen films during his career, which began with him working as an assistant director for Sergio Leone. He was also a screenwriter. The Spaghetti Western Database (what. You didn’t know there was such a thing?) describes a book about Valerii by Roberto Curti, titled Tonino Valerii: The Films. Not in my library, unfortunately. My Name is Nobody is #18 on the SWDB’s Essential Top 20 Films list.

A sort-of sequel to My Name in Nobody came out in 1975. Directed by Damiano Damiami, the Italian title was Un Genio, Due Campari, Un Pollo. In English, A Genius, Two Partners, and a Dupe (also, Nobody’s the Greatest). The comments I’ve seen aren’t enthusiastic, but I haven’t seen the film. It does, however, what is likely one of the oddest casts ever assembled for a Western: Terence Hill, Patrick McGoohan, French actress Miou-Miou, and Quebecois singer Robert Charlebois. Go figure. A copy is currently available on YouTube.