Johnny: “And what is it what goes on in this postmodernist gas chamber?

Night Watchman: “Nothing. It’s empty.”

Johnny: “So what is it you guard, then?”

Night Watchman: “Space.”

Johnny: “You’re guarding space? That’s stupid, isn’t it? Because someone could break in there and steal all the f—– space and you wouldn’t know it’s gone, would you?

Night Watchman: “Good point.”

Louise: “Were you bored in Manchester?”

Johnny: “Was I bored? No, I wasn’t bored! I’m never bored. That’s the trouble with all of you. You’ve had nature explained to you and you’re bored with it. You’ve had the living body explained to you and you’re bored with it. You’ve had the universe explained to you and you’re bored with it. So now you want new thrills and plenty of ‘em and it doesn’t matter how tawdry or vacuous. As long as it’s new, ask long as it’s new, as long as it flashes and fuckin’ bleeps in 40 fuckin’ different colours. Whatever else you can say about me I’m not fuckin’ bored. So how’s it going with you?”

Louise: “I’m a bit bored, actually.”

Some souls aren’t simply lost. They’re trashed. Drugs. Alcohol. Abuse. Mental illness. These souls are destined to crash and burn. As they implode or explode, the flames sear everyone around them.

But they are still loved.

There’s something in every soul that’s indestructible. An innate genius that shines its way through any number of layers of physical and emotional garbage. A parent may recognize it. A brother or a sister. A lover. A priest. A friend. Each may see a heart and mind that the rest of society has turned from in revulsion or condescension.

Sadly, love is not always salvation.

The damage will, as often as not, still be done. Some trajectories towards oblivion are unstoppable. Those continually seeking the devil at the crossroads will find him there. But, in the end, they will not go unmourned. Those who have seen that spark of genius, undimmed, will bear witness to it.

Some will transmute it into art.

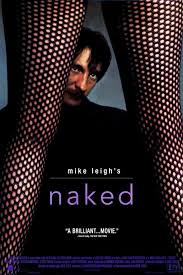

Mike Leigh’s Naked (1993) is alchemical. On one level, and along with Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, it’s the ugliest film I have ever reviewed. Ugly language. Ugly sex. Ugly flats. Ugly city. Ugly, brutal, cynical, stupid, feckless people. This is the kind of world where people answer a question like “Do you live ‘ere?” with “I do, unfortunately.” Where “Do you have any brothers and sisters?” is answered by “I try not to remember.” Or where the natural answer to the question “Does she like you?” is “Most people don’t.” Cinematographer Dick Pope manages to create a visual landscape of stark contrast, of claustrophobic stairwells and darkened alleys that make post-War Berlin look cheerful by comparison. Andrew Dickinson’s cascading minimalist music score of harp, viola and double bass could be the sound of the clock ticking down to Armageddon.

Is this really the cinematic environment in which you want to spend over two hours? It is. Art exists in part to redeem suffering. In Naked, Mike Leigh and his actors and his crew have delivered one of the most passionate eulogies in modern cinema. Even better, they’ve allowed the central character, Johnny (in a multiple-award-winning performance by David Thewlis), to deliver it while he’s still very much alive. In the midst of every conceivable kind of ugliness, Johnny’s nonstop verbal improvisations are breathtaking. For every profanity uttered, there’s a flash of wit, a turn of phrase, a free-form metaphysical ramble that lingers in the mind long after Johnny’s hobbled his way into oblivion. Isn’t it a fitting irony that, for a film I’ve called the ugliest I’ve reviewed, I’ve recorded more dialogue in my notes than for any other? And here’s another irony: At the same time this review is coming out, so is the latest filmed version of another of Shakespeare’s tragedies. It’s Titus Adronicus, Shakespeare’s goriest production. Coincidentally also filled with ugly, brutal, cynical, stupid, feckless people. The main difference between Johnny and Titus: Johnny has better lines.

There are a lot of people as bright and as doomed as Johnny out there in the real world. They’re like sharks who have to keep moving and hustling and talking to survive. Unfortunately, unlike sharks, they’re closer to the bottom of the food chain than the top. A lucky few, the Villons, the Rimbauds, the Célines, the Kerouacs and Kurt Cobains, manage to stop moving long enough to get their words on record before they’re swallowed up. Those words dazzle us and challenge us. To borrow Johnny’s from one of his diatribes against Divinity, he’s got a few fundamental questions for all of us. God is not spared. Neither are friends, or lovers, or a lonely waitress in a café, or a pair of Scottish drifters, or a guy sticking up Megadeath and Pantera posters. The response to Johnny’s use of language is variable: worship, affection, bewilderment, rage.

Words are so powerful in this movie. Johnny’s got a book in his hand as often as he’s got a cigarette in his mouth. A cheap display of elephants on the mantlepiece becomes, in Johnny’s vernacular, “the old diminishing pachyderm formation there”. A tattoo is an “ornithological mutilation”. A challenging knot in a corset becomes “a granny, a sheepshank, or the infamous round and two half-hitches as mentioned in the book of Ezekiel.” Every conversation he gets into walks a knife edge between fostering illusions and shattering them. The things he says, the questions he asks, tend to tear painful holes in whatever fragile cocoons in which his listeners have wrapped themselves. Johnny can talk with anybody. He just can’t guarantee that anyone, himself included, will survive the conversation. In one of his most despairing, bitter moments—suddenly rejected where he’s least expected it—he says, “No matter how many books you read, there is something in this world that you never ever ever ever ever fucking understand.” Another sad irony: any time Johnny talks to someone intelligent enough to appreciate his verbal sleight of hand, or maybe love him for it, he suddenly feels too threatened to stick around. He doesn’t want to be understood. The only shield for his very tattered armor is his sense of operating on a plane that can’t be pigeon-holed by anyone.

It’s a very lonely world when you despise the stupid and the clever.

Although David Thewlis’s performance is a tour de force (and the fact that he wasn’t even nominated for an Oscar an excellent illustration of the Academy’s limited vision), every actor in Naked is superb. Lesley Sharp plays Louise, an ex-lover of Johnny’s who’s trying to lead a “normal” working life in a London devoid of any sense of home. When she asks Johnny if he wants to see her room, he says “Is there anything worth seeing?” She suddenly realizes there isn’t. Katlin Cartlidge is Sophie, a victim in every sense of the word—addled by drugs, jobless, open to every sexual predator drawn by her pheromones. Drawn in by Johnny’s metaphysical rants is Peter Wight as Brian, the night watchman–a lonely man with a pointless job that allows him too much time to think and too little to interact with other people. And then there’s Ewen Bremner’s cruel and hilarious portrait of a young Scots drifter. Will anyone ever again take punks entirely seriously?

One of the main reasons that we can empathize with the characters in Naked, no matter how immoral or self-destructive they may be, comes from the unique way in which Mike Leigh goes about making his movies. He suggests a theme, and then he and his actors create the script in rehearsals. He films improvisations based on that script. The end result is realistic dialogue with none of the artificiality that sometimes tries to pass itself off as Art.

At this point, I would like to present my own special Oscar for the Best Supporting Performance In A Role That Shouldn’t Be In The Movie In The First Place. And the winner is Greg Cruttwell as Jeremy, one of the most repulsive characters ever brought to the screen. Director’s Leigh’s leftist politics got in the way of his better judgement. He needed a straw pig: a nouveau riche, Porsche-driving rapist to demonstrate that in the class war even a low-life like Johnny can be out-slimed by a psycho from the upper classes. What an astonishing revelation. Gosh, who woulda thunk it? Cruttwell succeeds in being supremely loathsome, but Mike Leigh could have cut every one of his scenes. There’s enough that is harrowing in Naked without throwing in cheap polemics on Class Consciousness.

At the end of Naked, Johnny is putting himself through a lot of pain to hobble off to nowhere. As usual, he’s already summed up his situation better than anyone else could: “I’ve got an infinite number of places to go, the problem is where to stay.”

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Johnny: In London, you’re only ever 30 ft. away from a rat.

——–

Johnny: No matter how many books you read, there is something in this world that you never ever ever ever ever fucking understand.

——–

Louise: What are you doing here? You look like shit.

Johnny: I’m just tryin’ to blend in with the surroundings.

——–

Johnny: D’you dream in Scotch?

Archie: Eh?

Johnny: Like dream about sporran-clad, caber-tossing haggis galloping over porridge-covered glens?

Nihilism. Anarchy. Five minutes into re-watching Naked, I was asking myself why in the hell I would have chosen this movie to review. Ten minutes in, David Thewlis’s performance fully kicked in and I remembered. Thewlis’s Johnny is the bastard son of Oscar Wilde and Charles Bukowski and sweeps all before him with a whirlwind of verbal pyrotechnics (“diminishing pachyderm formations,” “ornithological mutilations”), cutting wit, barbed questions, loathing of self & others, and a staggering capacity to channel empathy and bile in the same breath. He lives in an endless nightmarish present with no future, sustained by random encounters that are his only salvation from the mind-numbing boredom of trying to relate to pathetic creatures ignorant of their utter inconsequentiality in the face of the cosmos. In his own words, he’s a man who’s always got somewhere to go, but nowhere to stay. He’s a king’s Fool, and all four horsemen of the Apocalypse rolled into one. God help anyone with a fragile ego who happens to cross his path—he’s the therapist from hell. A session with Johnny is a likely lead-in to confusion, shame, despair, dismay, violence, and unemployment. Not only is there no silver lining, but the universe is going to piss on you every chance it gets. After all, what’s to say you haven’t already had the happiest moment of your life and it’s all downhill from here on? In a commentary on Naked, Neil Bute points out the David Thewlis gives a brilliant demonstration of acting as reaction to other characters, rather than action for its own sake.

I love the work of all of the actors in this film: Leslie Sharp’s no-nonsense, long-suffering Louise; Katrin Cartlidge’s walking-wounded Sophie; Ewan Bremner and Susan Vidler’s star-cursing lovers, Archie & Maggie; and Peter Wight’s hapless night watchman Brian. I’d also say something flattering about Greg Cruttwell as Jeremy, except I don’t really understand what he’s doing in this movie. It’s as if Christian Bale wandered into Leigh’s film from the set of American Psycho. Is there really a dramatic point to Jeremy, or was Leigh not quite sure that Thewlis, Sharp, and Cartlidge could carry the film on their own? As a study in sexual sadism, Jeremy is a movie unto himself. His every appearance in this one is merely a distraction from Thewlis’s main event.

Leslie Sharp has had a solid career, and continues to work at the time I’m writing this (2020). Katrin Cartlidge career was cut short; she died in 2002, at age 41, from pneumonia and septicemia. Ewan Bremner has over 100 acting credits as of 2020. Susan Vidler has worked mainly in television. Peter Wight must be one of the hardest-working actors in England, with 147 credits on Imdb. Greg Cruttwell seems to have given up acting after 1997. David Thewlis is currently just shy of 100 credits and deserves to win a few more awards than he has. Director Mike Leigh has been nominated for seven Oscars, having made 9 feature films since Naked. Give the guy a break, already.

For me, the three highlights of Naked on this second viewing were Johnny’s monologue (linking Revelations, Nostradamus, wormwood, bar codes, Chernobyl, and Universal Consciousness) in Brian’s empty office building, his monologue on walls with Poster Man, and his final stumbling yet relentless walk off the screen at the end.

I was also impressed by Andrew Dickson’s minimalist score and Dick Pope’s cinematography. Pope manages to highlight Johnny’s humanity while unsparingly capturing an urban landscape of desolation, sterility, and tawdriness. Dickson has scored only 7 feature films, while Pope has 64 credits as cinematographer (including two Oscar nominations, for Mr. Turner and The Illusionist).

An ideal double bill: Naked and Bruce Robinson’s Withnail & I.

Worthwhile checking out, two Criterion Collection essays on Naked, available through Imdb’s External Reviews section. One essay is Derek Malcolm’s “Naked: Desperate Days”; the other is Ian Buruma’s “Naked.”