https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Yo8bvg0MAg

“…And the 1992 Academy Award for Best Architecture in a Leading Role goes to….the extraordinary classical Chinese Estate featured in Raise the Red Lantern!! Accepting the award on behalf of the house are the director and the cinematographer of Raise the Red Lantern, Zhang Yimou and Zhao Fei…. ”

Although stranger things have probably happened on Oscar night, I did make this one up. Too bad. The house deserved the recognition. I can’t recall another film where a single set—in this case the massive, austere compound in which a rich man’s four wives play out a deadly domestic drama— has been used with such telling effect. Through superb editing and photography, a Ming Dynasty villa becomes the Orson Welles of architecture. It alternately wears the face of Greek tragic stage, of arid prison, of labyrinth-with-Minotaur, and of haunted house. It changes moods as the seasons go by, and as the red lanterns of the title cast their light and their pall over the inhabitants. It even has a voice, stone walls chiseling every sound into a preternatural clarity.

The house does such a great job playing its role, that the director of Raise the Red Lantern found it unnecessary to ever give the audience more than a glimpse of its actual owner. He is photographed from a distance, or through a curtain. At times, it is only his voice we hear. The entire, crushing weight of the patriarchal power structure he represents is embodied in the home in which he lives. Just as he has set up the rules of the game which his wives are forced to play, so every moment in the lives of these women is framed against a doorway, a roof line, the high walls of a room, the inflexible geometry of a corridor. Tyranny by architecture.

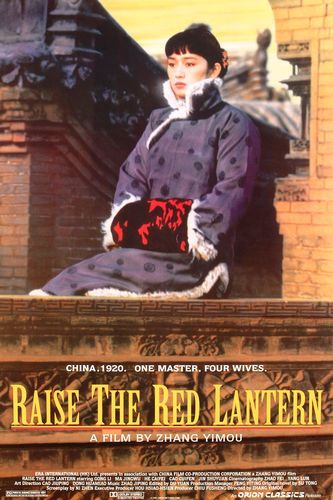

Metaphors come easily with this film. It resonates like Shakespearean tragedy. But before we get carried away with possible readings, let’s briefly recap the story itself. A 19-year-old girl, Songlian (Gong Li), finds her university studies put on permanent hold when the father who has supported her dies. Songlian chooses to become the concubine, the fourth “wife”, of a man of wealth. It is a desperate choice. And what she cannot realize is that the strength of character she brings to her new life—her intelligence, her pride, her independence— will be turned against her by a system of “domestic economy” that breeds intrigue & infighting of Machiavellian intensity. She will be destroyed by, and will herself destroy, the one person (a young servant girl, Yan’er [Kong Lin]) who most resembles her.

Reference books refer to the massive quality of Ming Dynasty architecture being “softened” by symmetry. You’d never know it by this film. Each line of Songlian’s new home cuts like a razor’s edge. This is fearful symmetry. Zhang Yimou’s camera is as ruthless as the architecture. The same close-up which introduces Songlian at the beginning of the film, returns near the end. No exit. The ticket is no longer valid for this journey.

Many readings of Raise the Red Lantern, beyond the obvious one of personal tragedy, are possible. Take your pick:

For Lantern as a veiled criticism of the policies of the Current Communist Chinese government, read Paragraph 1 below.

For Lantern as an attack on patriarchal, paternalistic, sexist societies, read Paragraph 2.

For Lantern as an allegory of colonialist exploitation of Third World Nations, read Paragraph 3.

Paragraph 1: A lot of people, especially since the Tiananmen Square massacre, would like to pick this option. Even the Chinese government did, when they banned the film immediately after its completion. Since then, however, they’ve changed their minds and allowed its release in China. They’re right. This isn’t a political diatribe. Unless you find a critique of Scottish politics to be one of the most fascinating aspects of Macbeth, I’d go on to Paragraph 2.

Paragraph 2: This one’s easy? The master of the household gives males a bad name. He treats his wives like children, to be spoiled when they satisfy his whims, punished when they do not. He thinks his “public” presence in a particular wife’s bed the ultimate honour to be afforded them. He can be petty, cruel and vain. And there is blood on his hands. You can stop there if you’re happy with overlaying our Western values on products of other cultures. Director Yimou might be damning Confucian paternalism, but I’d rather hear him say that himself. If one could ask Yuru (Jin Shuyuan), the neglected but dignified First Wife in Yimou’s film, for her opinions, her responses might surprise us. Would she trade her life for that offered by the modern West? The fates of Salman Rushdie and Taslima Nasrin certainly condemn intolerance, but do they condemn Islam? Go to Paragraph 3.

Paragraph 3: By promoting jealousies between his wives, the master of the house ensures his overall dominance will go unchallenged. Divide and conquer. Whatever the ultimate cost. This is a strategy that secular and ecclesiastical powers have applied without pity across the globe and throughout history. I cannot help seeing in the events of Raise the Red Lantern a microcosm of what nations have done on a genocidal scale—from the exploitation of Native tribal rivalries by early settlers in North America, to the bloodbaths that have washed over Burundi and Rwanda as the result of deliberate German and Belgian fostering of tribal inequities. But this gets me on a soapbox, so let’s just go back to the movie itself.

A quick note on the colour. If it strikes you as unusually vivid, it’s because it’s based on a three-strip Technicolor process long ago abandoned by Hollywood, but in the interim sold to China. Critic Roger Ebert says the process “allows a richness of red and yellows no longer possible in American films.”

A final word about ghosts. Although there is nothing truly supernatural in Raise the Red Lantern, director Zhang Yimou has taken a page from Shakespeare (Macbeth, Hamlet), Akira Kurasawa (Ran) and Shirley Jackson(We Have Always Lived in the Castle, The Haunting of Hill House): every wasted life creates its own ghosts. The ghosts are not real. But they are terrifying. Projections of what has been lost—freedom, honour, love, success- appearing to those left wandering in what author Jane Rule called “the desert of the heart.” In the end, Songlian acknowledges that they are her only companions:

“Good or bad, it’s all play-acting. If you play well you fool the others; if you play badly you only fool yourself. If you can’t even fool yourself, you can fool the ghosts. People can breathe, ghosts cannot. That’s the only difference. People are ghosts, and ghosts are people.”

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Whenever I’ve talked with friends or strangers about reviewing films, the question “What’s your favorite movie?” invariably pops up. My response is always something along the lines of “That’s an impossible question. Every genre has its own galaxy of great films, and there are a lot of genres. All I can do is rattle off some high points. It took Roger Ebert four volumes to cover his personal list of great films, and I don’t think he was finished.” While I’m saying that, however, my mind is flashing to a handful of movies that have taken up permanent residence in my filmic consciousness. Fritz Lang’s M and Metropolis, Buster Keaton’s The General, Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush, Akira Kurasawa’s Ran, Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus, Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s The Marriage of Maria Braun.

And, always, Raise the Red Lantern. In truth, it may be the most perfect film I know. Literally flawless. Here’s why:

- A genuinely tragic storyline, with a devastating, inevitable descent from hubris through to madness; also a devastating take on misogyny operating under the guise of tradition & wealth

- One of the finest performances by Li Gong, one of the most powerful actors on the planet, allied to a superb casting of supporting roles

- One of the world’s great directors, Yimou Zhang, working at the height of his craft

- Some of the most stunning set decoration and production design in the history of film

- Equally stunning cinematography

- A beautifully crafted, idiosyncratic musical score

Raise the Red Lantern manages to be simultaneously a story of a bird in a gilded cage and of rats in a behavioral sink. Both lyrical and gut-wrenching. Imagine all of the brutal Machiavellian intrigues of two centuries of Renaissance Italian politics condensed into a single Chinese household in the space of a year. If you’re asking me for one film that demonstrates everything cinema can be and can do, this is my choice.

One final thought. The dynamics of the polygamous household in Raise the Red Lantern is skewed by the scarcity of children in that household. It’s my understanding that it was quite possible for a similar Chinese household with four wives to have had two dozen children or more. The extended family could have had the effect of shifting the stifling interpersonal power plays between wives & concubines towards a larger social unit. Here in North America, we’ve had a chance to see some of this firsthand in the recent revelations about the polygamist breakaway fundamentalist Mormon communities located in Utah, northern Idaho, and southern British Columbia.

As Margaret Atwood did with Canada’s Royal Winnipeg Ballet and The Handmaid’s Tale, Yimou Zhang staged Raise the Red Lantern as a ballet with the National Ballet of China. That would have been something to see. YouTube has some excerpts from the production.