“The Rat, the Cat, and Lovell the Dog / Rule all England under the Hog.”

Richard III was not the most fortunate of the English kings. His name has been carried down in history as synonymous with villainy in its vilest forms. But had Richard been friends with either Conrad Black or Brian Mulroney, things might have turned out quite differently. The main damage to Richard III’s reputation was done by a gentleman named William Shakespeare. Will was interested in writing a brilliant historical play, rather than writing brilliant history. Having created a great villain, he was not about to let historical accuracy get in the way of character development. Neither Mr. Black nor Mr. Mulroney would have allowed such a calumny. On Richard’s behalf, they’d have sued Shakespeare for everything he was worth, bought the Globe theatre out from under him, and optioned the rights to his plays to the Vatican. The Tragedy of Richard III would have been tossed in the dustbin of ignominy, and William would have been too humiliated, broken, embarrassed or bitter to ever go on to write Hamlet, Othello, Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, King Lear, etc. For the hundreds of members of The Richard III Society, founded in England in 1924 and dedicated to redeeming their liege lord’s reputation (to the extent of picketing productions of the play and writing to cast members), this might have been a welcome turn of events. For the rest of us, libel chill on Will would have been a, well, tragedy.

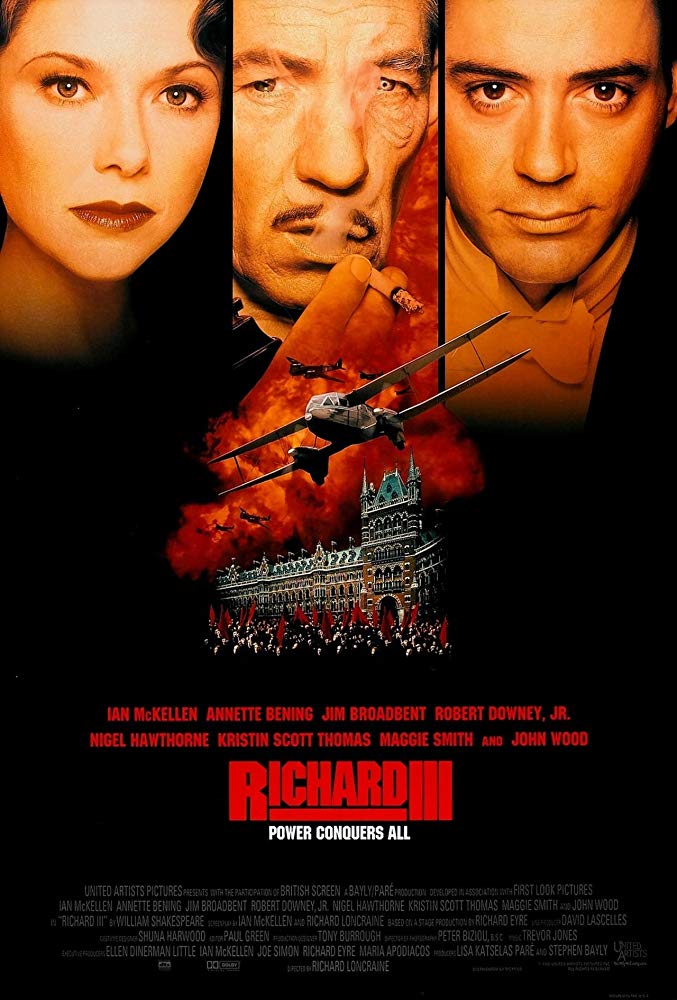

First, a bit of movie history. In the cinema, the last few years have seen a new Renaissance (excuse the pun) in movies based on Shakespearean plays. Previously, the standard had been set by Laurence Olivier in the 40’s and 50’s, with his versions of Henry V, Richard III, and Hamlet. Like Richard himself, Olivier cast a long shadow. Actor Anthony Sher, who played one of the most memorable recent Richards, wrote in his journal: “Wake inextricably depressed about Richard III. Why bother playing the part? Olivier’s interpretation is definitive and so famous that all around the world people can get up and do impersonations of it.” The post-Olivier years were not barren of striking film versions of the plays (Orson Welles’ Othello [1952] and Chimes at Midnight [1967], Akira Kurasawa’s Throne of Blood [1957] and Ran [1985], Peter Brooks’ King Lear [1970], Franco Zeffirelli’s The Taming of the Shrew [1966] and Romeo and Juliet [1968], Roman Polanski’s Macbeth [1971], and Grigori Kozintsev’s Hamlet [1964] & King Lear [1970]), but these were works of such disparate date, genius and nationality that their impact was individual rather than collective. In 1989, however, with the appearance of Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V, Olivier’s daunting ghost was laid to rest and William Shakespeare once again became become a very hot property. Besides the extraordinary Henry V, Branagh has directed Much Ado About Nothing [’93], A Midwinter’s Tale [’95], and Hamlet [’97]. Oliver Parker directed Branagh and Laurence Fisburne in Othello [’95]. Peter Greenaway did something with The Tempest and a lot of naked bodies in Prospero’s Books [’91]. Franco Zeffirelli and Mel Gibson tackled Hamlet [’90] again. Al Pacino explored the actor’s and audience’s fascination with Richard III in Looking for Richard [’97]. And not-quite-last and but most definitely least, Baz Luhrmann gave us the 1997 MTV pumped-up version of William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet, with large handguns.

Don’t get me wrong. I have nothing against using large handguns in Shakespearean productions. Armament for armament, director Richard Loncraine’s Richard III [1997], the inspiration for this month’s Seldom Seen, outguns Romeo + Juliet. Richard III virtually opens with a tank rather unexpectedly coming through a wall. There are more tanks, some strafing aircraft, and a lot of heavy machine guns at the end. Things blow up. What makes the ballistics of Loncraine’s film so different from Luhrmann’s is that Loncraine uses them to render the meaning of Shakespeare’s words absolutely clear to the audience, while Lurhmann uses noise to mask language he’s incapable of communicating. Richard III is so incredibly well constructed and performed that I’d almost wager that if someone came to the film ignorant of its authorship, he/she would be rivetted by the story and language and be utterly unaware that the words being spoken had been written in another century. For me, this disappearance of the archaism of Shakespeare’s language has always been the hallmark of a truly great production of his plays. Words become an obstacle in Shakespeare only when they are performed without understanding, or with an undue reverence for the past which inhibits risk-taking. I remember playing Macbeth in a junior high school production way, way back in Grade 9; the lines I truly understood I remember to this day and still marvel at, while other lines which I was too young or too unaware to grasp were immediately forgotten. The new Richard III comes with a money-back guarantee: you are either able to follow every nasty, deadly nuance of what Richard says, or your video rental is refunded.[1] This is as good as Shakespeare gets. If you walk away from this production not understanding why Shakespeare will always be relevant, both Ian McKellen (who plays the king) and Richard Loncraine will personally visit your home and flog themselves on your doorstep.[2]

This making of Shakespeare’s language transparent amounts almost to wizardry. It comes from every subtlety of intonation and facial & bodily expression an actor is capable of. It comes from action onstage which mimics what has been said, or reveals what words have only implied. And it comes from staging which creates a convincing world for the actors to inhabit. In Olivier’s Richard III, the set design was a kind of Technicolor Gothic Neo-Classicism, with splendid costuming and a good deal of monastic chanting and organ music. It was a clean, brightly-lit stage over which the twisted black shadow of Richard could fall to uncanny effect. In the new Richard III, Richard’s world is utterly unique. Production designer Tony Burrough has managed to create an alternate historical reality which is convincing down to its finest detail. And there is an infinite amount of fine detail, from ornate table settings to vaulted ceilings to Arc Deco factories to Big Band grandstands. What can we call this world? Perhaps Fascist Baroque Art Deco? Or Edwardian Industrial Gothic? I give up–I haven’t seen anything quite like this since Terry Gilliam’s Brazil. As if the set and performances weren’t enough, we get a swing version of Christopher Marlowe’s “Passionate Shepherd to His Love, ” and Armageddon with Al Jolson’s “Sittin’ on Top of the World.”

Ian McKellen is once again definitive as Richard. He’s every inch The Boar, “the bottled spider,” the “poisonous bunch-backed toad, “hell’s black intelligencer,”and the “elvish-marked, abortive, rooting hog.” He’s also the great seducer and the ultimate self-destroying tyrant. McKellen’s skill is awesome; he handles objects with his one unwithered hand as convincingly as if he himself had been born with Richard’s deformity. The manner in which he pulls off and offers Anne his ring for bethrothal is more horrifying even than the appalling manner of his enemy Rivers’ death. One thing McKeller didn’t abandon from Olivier’s performance was the use of Richard’s asides to the audience to draw us all in as guilty co-conspirators. He makes us intimate with himself, and the blood he sheds stains our hands.

If there was any weakness in Oliver’s Richard III, it was that the secondary characters paled beside Olivier’s performance. This is not the case the new version. Even though much of the cast had little Shakespearean training (including Annette Bening as Elizabeth and Robert Downey Jr. as Rivers), and McKellen’s is a tour de force, we strongly identify with each of Richard’s victims. In the face of his own mother’s [ Maggie Smith] final curse, even Richard flinches momentarily:

“No, by the holy rood, thou know’st it well,

Thou cam’st on earth to make the earth my hell.

A grievous burden was thy birth to me…. Bloody thou art, bloody will be thy end;

Shame serves thy life and doth thy death attend.”

Bad history. Great cinema. For an alternate take on Richard III himself, The Richard III and Yorkist History Server can be contacted at www.r3.org/.

[1]This offer void where the video store owners are entirely unaware that it exists.

[2]This offer void where Richard Loncraine and Ian McKellen are unaware that it exists.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Richard III was Shakespeare’s first real blockbuster hit, and this filmed version of the play shows you why. Although I could easily list a couple dozen Shakespeare plays on film I’ve enjoyed over the years, and shared with students and friends, Richard Loncraine’s Richard III continues to stand as a personal favorite. From that opening scene with the tank smashing through a wall and Ian McKellen’s heavy-breathing, gas-masked head popping out of the turret, this version grabs you and never lets you go. It’s the perfect fusion of Shakespeare and cinema, with a brilliant use of English locations such as the Battersea Power Station, the Brighton Pavilion, and the Steamtown Railway Museum. McKellen is superb in the title role.

The real fun, of course, is in trying to separate fact from fiction in Richard’s story. Shakespeare’s play was the ultimate triumph of art over history, of propaganda over historical record. Unlike his efforts to turn Joan of Arc into a cheap tart in Henry VI, Part I, the Bard’s demolition of Richard’s reputation was a total success. Subsequent critics and historians are still trying to pull the real king out of the rubble. What you’ll want to do after watching the film is take a look at some of the correctives. Isaac Asimov, in his lucid Asimov’s Guide to Shakespeare, does a fine job of dismantling many of the slanders and showing Richard as far more successful and far less culpable than in the play. Josephine Tey, in her last novel The Daughter of Time, went even further in clearing Richard’s name….and was probably at least partly responsible for the subsequent research into revisiting the historical record. I might have written more on the subject in this follow-up, but it’s been too long now since I looked at the differing accounts for me to try anything more comprehensive here.

What you don’t want to do is walk away from either the film or the play without at least taking a brief look at some of the varied perspectives. The members of the Richard III Society and The Richard III Foundation, Inc. will thank you. It’s quite possible that this king was no more of a consummate villain than Saint Joan was a whingeing strumpet. Shame on you, Will, you sly dog you.

Loncraine’s Richard III did get some strongly negative reviews. A lot of Shakespeare’s dialogue gets lost when you reduce a four-hour play (Shakespeare’s second-longest after Hamlet) to 110 minutes. In this case I think it works because Richard totally dominates the play (speaking almost a third of its 3600 lines) and Ian McKellen totally dominates the film. Hence, the spirit of the play is preserved in the film. And how fitting that a play which is a masterpiece of political propaganda should have a film adaptation that draws on Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will in its production design. I always return to the original text whenever I watch a screen version of any of Shakespeare’s plays; I love the language and never tire of going back to it. But I’ll rarely fault a director & cast for trying to shake things up. Akira Kurasawa’s Throne of Blood (1957) dispensed with Macbeth’s text entirely, and succeeded well enough to be restaged live at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival 53 years later. One of my favorite versions of Romeo and Juliet, Richard Monette’s for the Stratford Festival (1993), was set in the time of Mussolini. Baz Luhrmann reimagined Romeo + Juliet for the Fast & Furious generation. It’s all Shakespeare; it’s all good.