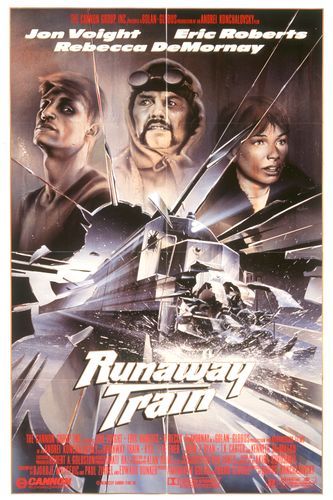

Do adventure stories get any better than this? Nah. The emphasis here is on the word story. Think back to your high school days when your English teacher tried to explain the meaning of “conflict” to you. The engine that powered a short story was a battle of man-against-nature, man-against-machine, man-against-man, man-against-himself. If these conflicts truly drive a narrative, then Runaway Train runs as relentlessly on all cylinders as the throttled-down locomotive that gives the movie its title.

From the opening shots of the film—cutting from the maximum security prison of Stonehaven (what a name!) locked in the no-man’s land of an Alaskan winter, to a full-scale riot within Stonehaven’s walls—the viewer knows it’s too late to go for the popcorn. Konchalovsky is in control. He sets the stage better in the first ten minutes than other directors do by the time the closing credits roll. The warden strides through the burning refuse of the riot, calmly informing the prisoners that they’re scum and will remain scum. Our first sight of Jon Voight—the prisoner who’s been welded into his cell for three years—has him doing push-ups in the darkness, more like a machine than a human being. Manny, the young punk who idolizes Voight, begins a non-stop marathon of nervous hyperactivity that would exhaust Rick Hansen.

A lesser storyteller would have stopped here and would rely on hammering the viewer into his seat with an avalanche of special effects and gut-wrenching violence. And occasionally, that kind of ride is worth it—I do recall applauding Sigourney Weaver at the end of Aliens. But a great story gives us more than an adrenaline rush. Konchalovsky gives us The Train.

The Train is alive. The Train is an actors’ stage barrelling seventy miles an hour into the Twilight Zone. The Train is a metaphor for heroism, savagery, freedom, and futility. Brilliant direction and cinematography, combined with an eerie understated musical score turn a locomotive into an Academy Award contender. The last time I can remember seeing such an uncanny metamorphosis was in William Friedkin’s underrated Sorcerer—a film which itself mirrors Runaway Train.

A word about the human performances. Superb. Perhaps the best tribute we can give to an actor is to say that he or she is virtually unrecognizable in the role they play. A classic example would be Catherine Deneuve in Roman Polanski’s Repulsion. Jon Voight manages a similar disappearing act in Runaway Train. Voight’s “If you could do this One Little Thing….” Soliloquy ranks up there with Brando’s “I coulda bin a contender….” As for the players, like Eric Roberts and John P. Ryan, whose roles serve as foils to Voight’s, all are uniformly fine.

Earlier, I mentioned travelling into the Twilight Zone. This is exactly where Runaway Train ends. It’s fitting that the screenplay should have originated with the great Japanese director Akira Kurasawa. In many of Kurasawa’s films there comes a moment when events push human beings beyond the point where a rational reaction is possible. In those moments, the filmmaker leaves us with images that literally haunt the mind. The closing shot of Runaway Train is astounding, impossible to watch without “Attended or alone,/ Without a tighter breathing,/ And zero at the bone.”

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Yeah, still kicks serious ass.

For some perspective on storytelling & moviemaking, try watching Runaway Train and Snowpiercer (2013) back-to-back. The former is a tall tale with mythic punch and characters that matter; the latter is an academic conceit tarted up with blood & gore. And if we’re talking trains, there’s no question whatsoever which one’s scarier. Snowpiercer has a prop; Konchalovsky’s train is Moby Dick.

One thing to which I paid a lot more attention on my last viewing of Runaway Train was the driving steampunked musical score by Trevor Jones. Jones also did fine work in The Last of the Mohicans, Richard III, and Dark City.