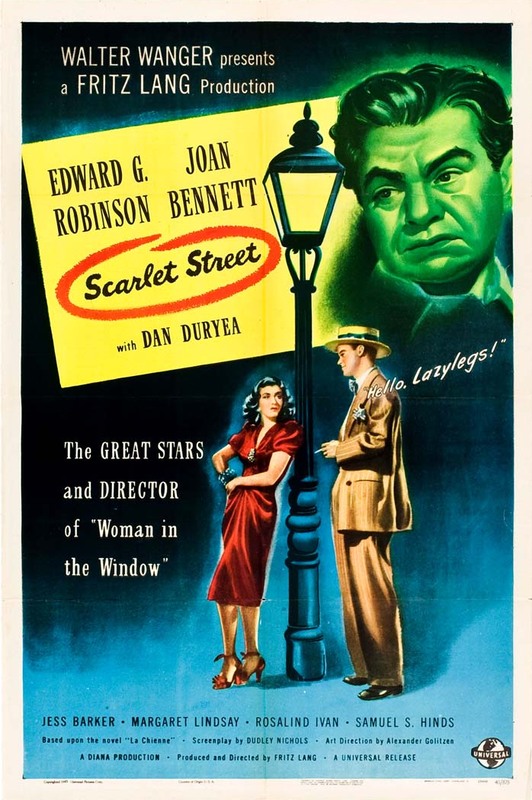

One of these years, I’ll get my timing right. It’s just occurred to me that reviewing Fritz Lang’s Scarlet Street (1945) in the same month as Valentine’s Day is about as apropos as writing about Lang’s M for the Christmas season. Unfortunately, I only have to time to check out one classic film a month, so I’m just going to have to plough right ahead and tell you about a romance that’s more disillusioning than anything even Johnny Cash could have conjured up on the darkest night of his soul.

Most film buffs know director Fritz Lang through his two silent masterpieces, Metropolis and M. Both have earned deserved places on critics’ “Best of All Time” lists. Far less well-known are the pictures he directed after he moved to America in 1934. Some of these were minor masterpieces that rank with the best of film noir—sordid tales of deception and betrayal. Lang was not in Hollywood to peddle fantasies of chorus girls finding rich husbands and landing starring roles in Broadway musicals. His first word as a child was probably the German equivalent for “irony.” It takes that kind of a mind to open with a movie like Scarlet Street with “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow” and close it with “Oh Come All Ye Faithful.” Blame it on his European upbringing. Who can grow up reading Faust and novels by Zola and Balzac and see in human passions anything but the possibility of catastrophe?

The protagonist of Scarlet Street, played to perfection by the great Edward G. Robinson, is a small-time cashier named Christopher Cross. Did I say irony? Even the guy’s name betrays him. Chris has spent twenty-five years doing everyone else’s bidding but his own. Very late in life, he’s wound up in an utterly loveless marriage with a woman whose heart is several sizes smaller than the Grinch’s. The only thing keeping him sane is the painting he does on Sundays, between bouts of cooking, cleaning, and being berated as a failure. Chris is actually a very fine painter; unlike his drab life, his pictures are strong naive-surrealist fantasies that turn his New York neighborhoods into scenes of other-worldly splendor or mystery.

One night, seeing his boss stepping out with a blonde young enough to be his granddaughter, Chris tells a co-worker, “I feel kind of lonely tonight. I wonder what it’s like, to be loved by a young girl like that….You know, nobody ever looked at me like that, even when I was young.” Chris is being wistful, not lecherous. He’s resigned himself to the fact that the world he lives in awards trophies to the winners in the game. For the others, there’s the gold watch after twenty-five years and a small bonus on the paycheck. Chris will never sell a painting. He’ll never be desired.

And then his dreams come true. Coming home late one night, he rescues a dark-haired beauty (Joan Bennett) from a vicious beating at the hands of an anonymous hood. She asks him to escort her home, and all of a sudden he’s not Christopher Cross anymore, he’s an artist and a hero, and the cage of his life is being burst asunder. Over drinks in Tiny’s Bar, Kitty March tells Chris she’s an actress. She never gets around to mentioning the name of the play she’s in. She’s also looking around kind of nervously, and asking about the bartender about someone named Johnny. Chris has the vaguest feeling of unease (who’s Johnny?), but he’s with a beautiful woman who knows him only as someone with a passion for art. Sure, he winces a bit when Kitty tells him, “You must be an artist! To think, I took you for a cashier.” Honest to the core, he’s letting himself be caught in a small lie because he knows he’s not going to get a second chance at living out this fantasy.

What a chump. The man he “rescued” Kitty from turns out to be her abusive lover. Johnny Prince (more irony) is a slick and self-deluded slimeball; he’s as single-minded and egocentric in seeking personal gratification as a baby at its mother’s breast. Played to perfection by Dan Duryea, Johnny is repellant narcissism at its purest. For Kitty, he’s not the villain you love to hate, but the one you’re hated for loving. Full of pipe dreams about quick bucks, Johnny steals from Kitty blind and slaps her around physically and verbally. Kitty revels in the abuse. The more she’s victimized, the more she has proof that Johnny really loves her. The logic is twisted but utterly convincing. Why would a man like Johnny hang around at all if she didn’t mean anything to him? The truth is that the only thing Johnny ever really sees is his own face in the mirror. Everything else is furniture–to be used, rented out, or sold outright.

Kitty is further trapped in her relationship because her only measure of manhood is the potential for violence. Chris’s schoolboy shyness is contemptible; a “real” man takes without asking or apologizing. Scarlet Street gives us one of the most convincing portrayals of an abusive relationship outside of Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh in Streetcar Named Desire. Johnny has no trouble persuading Kitty that they’ve got a sucker ripe for the gulling. Unable to be outraged by one’s own victimization, it is easy to let oneself be coerced into the victimization of others.

Of course, we are talking film noir here. I don’t want to you get the idea that Kitty March’s situation means the viewer spends the whole film empathizing with her entrapment. Kitty dissects Chris with surgical finesse. One feels a lot more sympathy with the frog than the scalpel. At one point, Bennett delivers what must rank as one of the cruellest one-liners in the history of cinema. Chris begs to paint her; she hands him some nail polish, points to her toes, and says, “They’ll be masterpieces.” Ouch.

Director Lang can be as cruel in his own way. Early in the film, he cuts from a sexy shot of Kitty, in dishabille, lying languidly on a couch (Johnny’s pet name for her, half-leering and half-contemptuous, is “Lazy Legs”), to a sink piled full of dishes dirty enough to cause cockroaches to swoon in anticipation. That sink remains a pretty effective metaphor as the story speeds along.

True to his losing style, Johnny has once again bet on the wrong roll of the dice. He and Kitty think they’ve hooked a $50,000-a-picture Greenwich artist, instead of a minimum-wage Brooklyn bookkeeper. By the time the plot’s worked itself out, with a couple of bizarre twists worthy of the director of M, there’s a lot of damage done. Some audiences were outraged. They were a lot more comfortable with The Lone Ranger than with something which was probably spiritually more akin to Bertold Brecht and The Threepenny Opera. The movie was banned in New York as “immoral, indecent, corrupt, and tending to incite crime.” Certainly, Scarlet Street was the first American film in which a murderer went unpunished by the law. But to call the film immoral was as ludicrous as saying that the story of Abraham and Isaac encourages infanticide. What people were really reacting to were the riveting performances of Duryea and Bennett. They’re monsters.

Scarlet Street makes superb use of sound for dramatic effect, and there’s a master class in black & white photography by Academy Award-winning cinematographer Milton Krasner.

Sidebar #76e: Looking Back & Second Thoughts

I don’t have a lot to add to my original review. Scarlet Street remains one of my favorite film noirs (my Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary says that ‘films noir’ and ‘films noirs’ are also legitimate plurals—proving that I’m not the only one confused), both on the strength of the story and the superb casting. This is the only Hollywood film I know that could be paired by Josef von Sternberg’s Der blaue Engel (The Blue Angel) from 1930. I’d also pair it with Akira Kurasawa’s Ikiru, imagining what might have happened if Kurasawa’s beleaguered protagonist had had the misfortune of running into a Japanese femme fatale.

I had the pleasure of knowing Dan Duryea’s son, Peter Duryea, who lived about a dozen miles down the road from me, and was the founder of the Guiding Hands Recreation Society that ran the local Tipi Camp Nature Retreat on Kootenay Lake for over 30 years. Unlike the characters often portrayed by his father, Peter was one of the kindest and gentlest souls I’ve ever met.