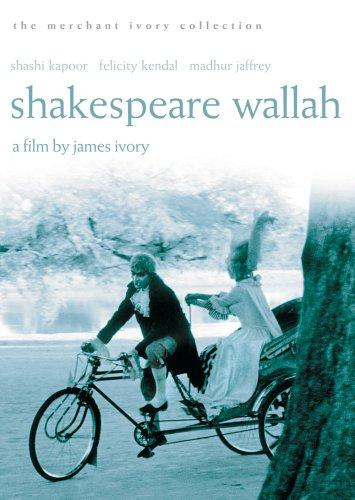

Things are usually fascinating on the border lands. Borders between countries breed strange fusions of languages, twilight and dawn are freighted with metaphor and inklings of magic, and solid matter shades into metaphysics at the quantum level. Director James Ivory’s Shakespeare Wallah (1965), one of the many interesting films now available at the Riondel Market, is the story of a group of people caught on a shifting historical frontier. Itinerant British Shakepearean players, the Buckinghams (father, mother, and daughter) find themselves increasingly irrelevant in a post-Raj India that is establishing its own cultural priorities. Where they were once the proud torchbearers for the greatest icon of British culture, the Buckingham’s find that recent Indian history has made them Shakespeare “wallahs,” a Hindi term somewhat akin to “peddler.” The schools which once booked the troupe for four or five performances, now find no time for Shakespeare in busy schedules which include cricket and guest speakers from the Ministry of Mines and Fuel. To add insult to injury, a native Indian cinema is in full flower, and its aristocracy of pampered, adulated superstars scorns classical Shakespearean theatre as an incomprehensible exercise in “moaning and groaning.” Their audiences follow suit.

Like the Buckinghams themselves, Shakespeare Wallah‘s main Indian protagonist, a wealthy young playboy named Sanju, is confused by the changes in the society around him. His mistress, Manjula, is a famous actress who incarnates all the worst & best qualities of the new Indian cinema—wealth, vanity, melodrama, intolerance, ambition, energy, sensuality, pride. She shamelessly bribes photographers for giant close-ups, and reminds Sanju that “where I go hundreds, thousands follow me.”

But Sanju’s also irresistibly attracted by the Buckingham’s young daughter, Lizzie. Unfortunately for both of them, his passion is rooted in a nostalgia for the vanishing Empire. He loves the girl, but he loves even more the feeling of being part of a “classic” British scene which stands the Bard’s timeless drama against the shallowness of Manjula’s unabashedly ephemeral “filmi” (“…always the same: singing, dancing, tears, love”). Confronted by Lizzie over his liaison with Manjula, Sanju gives the game away when he says: “What do I care for her? She’s only an actress.” A very odd comment to make to a girl who has spent her whole life on the stage with her parents. The moment Sanju begins to see the human being behind his idealized fantasy of Lizzie, things fall apart.

Shakespeare Wallah was the second film made by the now-famous team of director James Ivory, producer Ismail Merchant, and screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. Thanks to later films such as The Europeans, Heat and Dust, Jane Austen in Manhattan, A Room With a View, Maurice, and The Remains of the Day, the team of Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala has the kind of drawing power among cinematic literati that the James Cameron-Arnold Schwarzenegger team has among the action crowd. It seems fitting that the vast cultural mosaic that is modem India should have brought together a documentary film maker from Berkeley, California, a producer bprm in Bombay, and a Polish- Jewish writer from Cologne, Germany, who became an Indian by marriage.

Visually, Shakespeare Wallah, shot in black & white, echoes both the spare abstraction of Michelangelo, Antonioni and the eerie mysticism of Akira Kurasawa. There is an inherent strangeness in scenes of Shakespeare played against the backdrop of India’s endless temples and million gods. The film’s music has a cacophonous quality, as if all those temples and gods were insisting on a voice. One cannot help but wonder what an Indian version of Macbeth would look like.

It would be interesting. One of the ancillary pleasures of Shakespeare Wallah is the glimpse it affords of the very rarely seen (in the West) popular cinema of India—Bollywood. No kidding. Bollywood is the nickname given to the largest movie industry on the planet. It’s centered in Bombay, India. Whereas the American studios are currently producing some 200 films a year, the Indian movie industry’s current output is 800 films. According to a recent article by Anthony Spaeth in the May 8th issue of Time magazine, 500 000 people are employed by the industry in Bombay alone. As of 1980, there were 60 major studios and 1000 independent producers. The first Indian film dates back to 1897.

Aimed at a subcontinent with 800 spoken languages, India regularly produces films in a dozen languages. It’s probably the most culturally diverse cinema in the world. Yet with the exception of a handful of Merchant-Ivory productions and the work of the great director Satyajit Ray, Indian cinema is almost completely unknown and ignored in the West. This may slowly change as expanded cable systems and satellite television make multicultural programming available to more and more people. It then remains to be seen whether the cultural gaps can be bridged. Like American films, much of India’s mammoth production demands a significant suspension of disbelief. Unfortunately, it’s not the same suspension we’re used to here. A typical Hollywood hit involves invulnerable hunks using maximum firepower to wreak vengeance on maximally evil but technologically sophisticated slime balls in a phantasmagoria of stunt action and special effects. Or, to balance out the karma, great-looking, sensitive-but-confused young people exploring intimate relationships in colorful settings. In India, as Spaeth describes it, the formula is “preposterous escapism featuring bosomy starlets, sneering villains, sentiment as thick as the Bombay humidity and a minimum of six lip-synched songs accompanied by glissando violins and dance numbers as silly as cinema has ever seen.” One early sound film, made in 1932, had seventy songs. MTV on musical and moral steroids. Try imagining a didactic Last Action Hero, written for Elvis and Ginger Rogers, and shot on a shoestring budget. Now that’s entertainment.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

First off, I have to admit that in the years following my original review I fell in love with Indian films. I have a shelf of both sublime and sublimely silly DVDs. Although nowadays the internet offers much of the Bollywood canon free via YouTube and other sources, years ago I was lucky enough to be able to buy the latest popular films at my local Wal-Mart (a marketing mystery I’ve never been able to solve) and at a hole-in-the-wall Indian video store in Vancouver. Several of the musicals have given me the same joy I experienced watching The Rocky Horror Picture Show, The Phantom of the Paradise, and Viva Las Vegas! I’m not sure my friends and family understand….

Shakespeare Wallah is a gentle film about small dramas set within the larger currents of a rapidly developing post-indepence India. The mixed troupe of Shakespearean actors, some born in England and some who have never been outside India, is struggling to survive in a new age epitomized by the school administrator who turns them away with a curt “Where’s the time?” After all, it’s cricket season. Yet it’s not hard to believe Tony Buckingham’s claim that they once did 6 or 7 shows at their annual visits to the same school. Even in the late 1940’s there was a side to India that was timeless, easily overlapping, in its dissolving vestiges of royal houses and aristocratic privilege and rigid class structures, with the Renaissance England of Shakespeare’s time. Indian rajahs and princelings could still recognize themselves in the kings and queens, the dukes and duchesses, that the Buckingham Players brought vividly to life on stage. And India being one of the great repositories of epic storytelling, how could the works of one of the world’s greatest storytellers not fail to find an audience?

But at the time the film takes place, palaces are starting to being sold off or converted into office space. The automobile is coming into its own. The vast industry that would soon be known as Bollywood is sweeping the cultural landscape. Even a travelling showman with a couple of clever monkeys is feels the pinch of changing audience expectations. We empathize with the Buckinghams because they’re genuinely passionate about their art; it seems unfair that dedication to so noble a cause should go unrewarded. Shakespeare has been their lives. The fragments of plays we see in the film—Hamlet, Othello, Twelfth Night—are superb. The actors who played the lead roles were in real life part of a classical theater group called Shakespeareana that toured India for decades. The film draws on their experiences. Ideally, Shakespeare and filmi should co-exist—and perhaps in the 21st century they do—but in 1955 [?] the new was pushing hard against the old. The actress Manjula represents the new wave, shallow as a puddle, worshipped by millions.

Shakespeare Wallah also gives us a classic interracial love story, with the tensions inherent in conflicting cultural expectations and, perhaps, a simple case of I-love-you-with-my-heart-and-soul versus maybe-not-so-much.

This is one of the earliest of the Merchant-Ivory films, and only the second time James Ivory had directed a fictional film. The enormously-talented Merchant-Ivory team was falling into place, with Ruth Prawer Jhabvala co-writing the screenplay and Subrata Mita doing the cinematography. The great Indian director Satyajit Ray provided the music. Over 30 films later, James Ivory has yet to take home an Oscar. Maybe they’re waiting for the Lifetime Achievement Award.