This review is set up the way movies sometimes used to be: a short, followed by a double feature presentation. You remember shorts, don’t you? Those wonderful little documentaries on hot topics such as “A Tuber Plantation in the Andes”, “Wool Carding in Baluchistan”, and “Snorkeling the Everglades”? That bizarre, educational fifteen-minute interlude you & your date would share before William Castle came on the screen and announced that his latest chiller just might be too much for your heart, and death insurance was on sale in the lobby. But don’t panic; the only things you might need for this month’s Seldom Seen are a pair of dancing shoes and a hardwood floor.

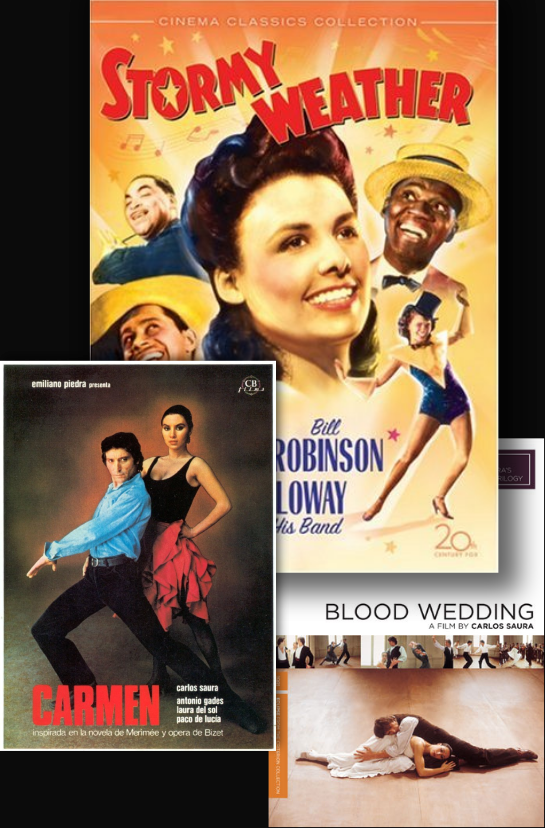

The short feature is actually brought to you by the Fast Forward and Rewind buttons on your VCR. They make it possible to turn 77 minutes of loose plotting into 30 minutes of sensational musical entertainment. Stormy Weather (1943, at the Riondel Market) has plotting and dialogue as bad as they come, and they come pretty bad. Although the entire cast is black, there is enough racial stereotyping going on here to bring Malcolm X back from the grave. But grab onto that remote control! Stormy Weather also has, thanks to Cab Calloway, Lena Horne & Katherine Dunham, and the Nicholas Brothers, some of the best musical numbers I have ever seen anywhere. A celebration of everything great song and dance can be: sultry lyrics, superhuman energy, inimitable grace, sheer joy. I’ve never paid a whole lot of attention to musicals, but the Nicholas Brothers have shown me the error of my ways. What they do on a dance floor lesser mortals don’t even fantasize about [WARNING: Do not try these moves in your own home]. And what can anyone say about bandleader Cab Calloway? If you can watch this zoot-suited unholy avatar of Lawrence Welk and Prince and not find yourself shouting I FEEL GOOOOD!!! it’s time to check your pulse. You might be dead. And that ain’t all, folks. The routines I was just describing are at the very end of the film. To give your Fast Forward button a rest about a third of the way through there are also a couple of other back-to-back gems. In the first, Fats Waller does “Ain’t Misbehavin'” as only Fats Waller could. In the second, Waller is also in on a lethal blues number by a lady named Ada Brown. Topping it all off is some clever camerawork & lighting (check out the shadows those hom players throw on the walls!)

Luck is something Antonio Gades certainly doesn’t need. Gades is the choreographer and lead dancer of a unique trilogy of films by Spanish director Carlos Saura. With Blood Wedding (1981), Carmen (1983), and El Amour Brujo (1986), the team of Gades and Saura succeeded in capturing the beauty and fire of flamenco on screen. In the process, they also managed to create their own hybrid of documentary and story, of spectacle and intimacy. For both aficionados and those unfamiliar with flamenco, these movies are a revelation. Of all the traditional styles of dance I have seen, flamenco has always seemed to me the most theatrical, the most passionate. Its discipline is as exacting as ballet, its precision at times almost superhuman, its songs and guitar lines stirring, and its aura intensely provocative and sensual. In the rehearsal sequence at the beginning of Blood Wedding, Antonio Gades repeatedly urges his dancers to “endure it”. And what the dancers “endure”, we marvel at. In a flamenco pas de deux, the man is all whiplash steel; the woman is the forge’s fire which shapes him. Immovable object meeting irresistable force.

Where where where /Is my Gypsy Wife tonight I’ve heard all the wild reports/ They can’t be right

Blood Wedding is based on a play by the great Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca. The story is the classic, inevitably tragic one of the man who deserts his wife for the lover whose passion is perfect because it impossible. Fatal Attraction, with style. The film’s introduction takes us backstage as dancers and musicians prepare for a dress rehearsal. We hear idle talk, see dancers creating their own personal spaces with pictures of family and saints pulled from travel bags, watch makeup and costuming. The dancers themselves seem much like the Gypsies among whom flamenco originated. When they assemble for warmups, there is true Gypsy sorcery as random activity coalesces into choreographed perfection. Literally spellbinding is the sound of all those heels striking the hardwood floor in rhythm, the synchronous handclapping, the sweep of hip & curve of arm. Nothing in these films diverts us from the dance itself. The decors are stark white & black, stripped of furniture or props.

The silver knives are flashing/In the tired old cafe A ghost climbs on the table/In a bridal negligee

The warmups over, the remainder of the film is the ballet itself. Technically correct, the description “flamenco ballet” seems oxymoronic. Classical ballet is flow and soft edges; flamenco is Tai Chi with attitude. It is all Edge. Cristina Hoyos is Gades’ prima ballerina, the femme fatale in Blood Wedding and the rival in Carmen. Juan Antonio Jiménez is both times Gades’ foil. The lead musician is Paco de Lucia. Highlights of Blood Wedding include Gades’ & Hoyos’ pas de deux, the raucous wedding scene, and the eerie slow motion duel (done without special effects) with very large knives.

She says, My body is the light/My body is the way

I raise my arm against it all/And I catch the bride’s bouquet And where where is my Gypsy Wife tonight?

Carmen again centers around a rehearsal. The storyline is that of Bizet’s opera. Love hasn’t gotten any safer. Only this time neither the actors within the film nor the viewers outside it knows where the story ends and real life begins. Are the dancers rehearsing Carmen, or.enacting it? It’s all Pirandellian—that neat adjective named after the Italian writer for whom reality and illusion were inseparable. The paradoxes work because the dancers flesh them out. Laura del Sol, as Carmen, is the kind of woman one suspects Leonard Cohen had in mind for a lot his songs—including “The Gypsy’s Wife” quoted here. Highlights of Saura’s Carmen include a castanet lesson en masse, a flamenco showdown between del Sol and Hoyos, and the “cane strut* of Gades and Jimenéz. ¡Caramba!

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Stormy Weather:

So right, so wrong. I’m so embarrassed by a remark in my original review about turning “77 minutes of general mediocrity into 20 minutes of sensational entertainment” that I changed it. I was out of line. The film has flaws, but mediocre it’s not. And I’m not sure what I was thinking when I faulted this all-black film for racial stereotyping. It likely was the genuinely weird concept of black performers doing black-face routines (although this Miller & Hays minstrel routine is as verbally clever as the Marx Brothers). There’s stereotyping here—all the usual kinds of clichés one finds in backstage-style musicals—but the only flaws I see now are a lightweight script and a couple of run-of-the-mill production numbers. The plot is a very loose biography of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, one of the world’s greatest tap dancers, and both Robinson and his screen buddy Dooley Wilson have a roguish charm that never outlives its welcome. I was glad I was able to get a hold of a copy of Stormy Weather (a YouTube purchase) because this time ‘round I was able to focus on the music & dance & personalities and let the script go by the board. It’s something I’ve learned from watching a raft of musicals over the last few years. If a film has one great dance number, I’m a satisfied customer. And Stormy Weather has more than its fair share. I don’t take back a word about what I said about the performances. Where else are you going to see Lena Horne, the Nicholas Brothers, Cab Calloway, Katherine Dunham, Benny Carter, and Ada Brown in their prime? Robinson himself may not have been in his prime, but he still had the magic. What I’d add here is that there are three lovely numbers by Ms. Horn, and even knowing what the Nicholas Brothers are capable of doing didn’t stop me from having to pick my jaw up from the floor. The Katherine Dunham dance piece for “Stormy Weather” is about as sexy as musicals ever get. Dunham’s own life story would make a terrific movie in itself, going from working on a graduate degree in cultural anthropology, to studying Haitian Vodun rituals, to founding her own dance company and e becoming the “matriarch and queen mother of black dance” in America, to at age 83 carrying out a 47-day hunger strike on behalf of Haitian boat-people. Among those she inspired were master choreographer Alvin Ailey and author/filmmaker Maya Deren. Food for thought—two out of the three books on American musicals that I have in my library make no mention of Stormy Weather.

Blood Wedding & Carmen:

Carlos Saura has never let me down. He remains one of the greatest of Spanish directors, and he’s followed the Flamenco Trilogy with other memorable dance-based films and movies in a multitude of other genres. It occurred to me when I watched these two films again that part of the magic comes from the fact that by featuring fragments of rehearsals as well as full-on performances the viewer has a better chance of appreciating the subtleties of the artistry involved. Not that with the likes of Antonio Gades, Cristina Hoyos, Juan Antonio Jiménez, and Laura del Sol the artistry isn’t already dazzling. I could write more, but it would just be a string of superlatives….Oh yes, one thing: those switchblade knives they used at the end of Blood Wedding may have been props, but they’re freakin’ scary.