Rose: Could you make a torpedo?

Charlie: How ‘s that, Miss?

Rose: Could you make a torpedo?

Charlie: A torpedo?…You don’t really know what you’re askin’. You see, there ain’t nothin’ so complicated as the inside of a torpedo. It’s got gyroscopes, compressed air chambers, compensating cylinders….

Rose (unperturbed): But all those things, those gyroscopes and things, they’re only to make it go, aren’t they?

Charlie: Yeah. Yeah, go and hit what it’s aimed at.

Rose: Well, we’ve got The African Queen.

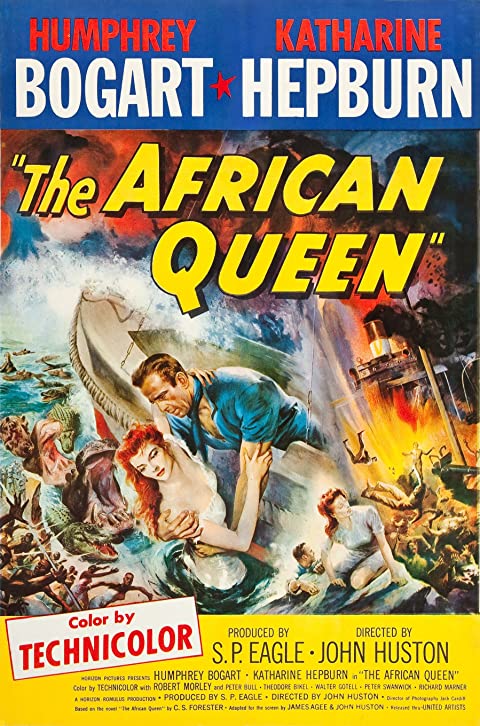

Some of you who have been checking in on this column over the last few years might have noticed that I’m not particularly good at synching my reviews to seasonal themes. The Christmas Mainsireet is likelier to have a review of Aguirre: The Wrath of God than The Miracle on 34lh Street. The June Mother’s Day edition will feature The Good, the Bad. and the Ugly instead of, say, I Remember Mama. That’s not irony on my part; I’m just operating off a very limited range of choices in any given month. I’m pleased to report, however, that I’ve finally lucked out in the timeliness department. February means Valentine’s Day. What could be more appropriate than a review of John Huston’s classic romantic adventure The African Queen (1951)?

Not just classic. Classy. One of the classiest romances in the history of the movies. Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn at their very best. A romantic partnership to die for.

Not that The African Queen is a flawless gem. It does possibly have the silliest ending of any film of its stature. Imagine the wizened ship’s captain—having cleverly jerry-rigged two torpedoes out of oxygen tanks, wood, nails, rifle cartridges and blasting gelatine—poking those same torpedoes out of two holes cut in the boat’s prow just above the water line and then choosing to sail out to attack in the middle of a storm. Gee, the boat sinks. Having gleefully abandoned any pretense to common sense, Huston then went whole hog and ended the picture with a coincidental rescue that surely left deus ex machina blushing.

Minor quibbles. The plot of the film scarcely matters. It serves its purpose simply by getting Bogart and Hepburn together for the 100 minutes it takes them to work their magic. Katharine Hepburn plays Rose Thayer, the stiff-upper-lipped spinstress sister to Robert Morley’s failed Congo missionary, Samuel Thayer. Rose had accompanied her brother to German East Africa in 1904. Together they ran the Is‘ Methodist Church of Kung Du for some ten years. We see that the native congregation, while enthusiastic, has the most tenuous hold on Christianity imaginable. Reverend Samuel has ended up in Africa because he failed in his ministerial ambitions back home; it looks like lie’s only marginally more successful in Africa. When both church and village are burned to the ground by a small German expeditionary force, we immediately understand that it has only been thanks to Rose’s strength that the mission had had even its modest success.

Samuel doesn’t survive the destruction of his brief life’s work. Rose is left utterly alone. Into the picture sails the unlikeliest knight errant ever—Charlie Allnut, skipper of a rust-bucket mail boat called The African Queen. The Oueen is the maritime equivalent of the ’65 Olds where you have to stick the screwdriver down the carburetor to get it going on cold days. Charlie is in about the same shape as his boat. He’s a decent guy who’s gone to seed. Before the German raid, we’d seen him sipping tea with the Thayers—his stomach growling volcanically and himself looking as stiffly out-of-place as a hippo at a prom. It turns out that Charlie is actually a down-on-his-luck Canadian engineer, another bit of plotting that strains credulity but perhaps Charlie’s goal in life is to drink gin, kick the Queen’s boiler every now and then as therapy, and avoid trouble. Motto: “Never do today what you can put off till tomorrow.” His passenger, of course, wants him to shape up and be a war hero. She may have lost the Mission to the Germans, but she isn’t going to take injustice lying down. There’s a 100-ton German steamer with a 6-inch gun out on Lake Victoria just waiting to be sunk, and no small obstacles like heavily-armed riverside fortifications, 100 miles of rapids, and some uncharted swamps should discourage the true patriot from doing what needs to be done.

Charlie has a few qualms. After he’s thought it over a little (and watered those qualms with healthy doses of gin), he decides his passenger’s loony. He tells her the plan is absurd. Rose tells him lie’s a coward. Responding in kind and with drunken candor he accuses her of being “a crazy, psalm-singing, skinny old maid.” Shortly thereafter, Rose dumps out his two-case supply of gin, Charlie sobers up, magic happens.

There’s no simple explanation for why Hepburn and Bogart’s on-screen romance rings so true. Certainly, there was a genuine chemistry between the two stars. They were in the hands of a master director. The screenplay gave both characters a fine balance of intelligence, strength, courage, and dignity. Ironically, the love affair was not even a part of the C.S. Forrester novel on which The African Queen was based. The early drafts of the screenplay, worked on jointly by John Huston and James Agee, had no humor. It was only when the two stars were thrown together in the sweltering, dysentery-ridden location shoot that movie history was made.

Filming in the Belgian Congo was a story that rivaled Queen’s fictional plot. Hepburn wrote her own book about it, called The Making of the African Queen or, How I Went to Africa with Bogart, Bacall, and Huston and Almost Lost My Mind. Peter Viertel, who replaced James Agee after Huston’s hard- drinking, hard-working gonzo lifestyle probably contributed to Agee’s heart attack, also chronicled the making of The African Queen in the excellent White Hunter. Black Heart. Viertel wrote that Huston seemed more interested in bagging an elephant than ii completing the film—which may explain some of its rougher edges. (For the curious, Clint Eastwood turned While Hunter. Black Heart into an undeservedly neglected film in 1990.)

According to Huston, one of the keys to getting the Charlie-Rose pairing to work was his suggestion that Hepburn play Rose as if she were Eleanor Roosevelt. Another key point is the fact that the two players address one another as ‘‘Mr. Allnut” and “Miss” for half the film. They don’t switch to a first-name basis until they ‘ve gone from mutual loathing and suspicion to being ready for their first kiss. It’s all so darned, well, innocent. The perfect antidote to all those cynical modern films with sad sex and irrelevant names. And can there be a more truly Canadian romantic moment than that of a couple pumping bilgewater together in a boat?

The closest Rose and Charlie get to sex is Rose’s unguarded description of her first experience of running rapids: “I never dreamed that any mere physical experience would be so exciting!…I can hardly wait…Now’ that I’ve had a taste of it. I don’t wonder that you love boating, Mr. Allnut!” This from the lady who at another point primly proclaims, “Nature, Mr. Allnut, is what we are put in this world to rise above.” Rose helps Charlie snap out of his boozy little world of comfortable self-pity; he puts her in touch with the sensual world she’d allowed to be shut out by the walls of her brother’s church.

From that first run down the rapids, Charlie and Rose operate as a partnership of equals. Charlie is seduced by Rose’s spirit first, her beauty second. Ditto for Rose. Rose makes tea for Charlie; Charlie makes tea for Rose. Charlie dives under the boat to free a twisted propeller; Rose dives under there with him to help. Charlie drags the African Queen through a leech-infested papyrus swamp; Rose salts the leeches down, pulls them off him, gives him the courage to go back into the water.

One final note. The way Bogart communicates Charlie’s revulsion for leeches, shivering as if in the grip of a fever, makes it obvious how fine an actor he was. The African Queen garnered Bogart his only Oscar, unexpectedly beating out Marlon Brando in Streetcar Named Desire and reflecting the Academy ‘s belated recognition of his brilliant roles in a string of masterpieces including Casablanca, Treasure of the Sierra Madre and The Maltese Falcon.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

“Could you make a torpedo?” –Rose

———

“What a time we had Rosie, what a time we had.” –Charlie

———-

Charlie: What are you being so mean for, Miss? A man takes a drop too much once in a while, it’s only human nature.

Rose: Nature, Mr. Allnutt, is what we are put in this world to rise above.

Still a classic, classic love story with a wallop of high adventure. Bogart and Hepburn are unbeatable as opposites who inevitably attract. It probably didn’t hurt that they were playing so true to their own characters—Bogart as the man’s man with a heart of gold; Hepburn as a woman who grows into her own strength, indomitable and irresistibly feisty. John Huston & James Agee do a superb job adapting Forester’s novel, and Huston makes masterful use of his stars and of his location shooting in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Kudos also to Robert Morley, who in a few minutes of screen time creates a genuinely tragic character. The Reverend Samuel Sayer’s entire life flashes before our eyes, from an understanding his youthful failure to realize his dreams of a ministry in England, to his struggle to build a congregation in a remote backwater of the African continent, to his death as a broken man when that Mission is destroyed. Samuel confesses to Rose: “I’ve got no facility…Oh Lord, I’ve tried so hard!” It’s an Oscar-worthy performance, despite its brevity.

The early scene of the Africans in the church does strike me as a bit cringe-worthy nowadays, as well as being a poor reflection on the ten years that Samuel and Rose have invested in shepherding their parishioners’ souls and voices. Perhaps, however, the state of the church simply reflects Rose’s willingness to set aside her own intelligence and strength of will to spare her brother’s pride. She couldn’t take away from him the only thing he could make of his life.

Not that I’m complaining, but I’m unsure why Huston and James Agee decided that Charlie Allnutt was going to be a Canadian. They may have wanted a British subject because at the point in time the story takes place the Americans weren’t yet in the war. The original Allnutt was a Cockney, not an option with Bogart. I’m just going to add Huston and Agee’s Allnutt to my list of random Canadians in the movies.

I mocked the ending of The African Queen in my original review. I take it back. The ending is silly and hopelessly romantic but it’s perfect for the film. I much prefer it to the grimmer, more “realistic” ending of the novel. Book and film are different creatures. Although much of the movie is, to its credit, faithful to the source, the screenplay’s development is ultimately faithful to the chemistry of the lead actors. As it should be. I read somewhere that C.S. Forester himself wasn’t entirely satisfied with the way he’d ended his novel.

If you have the chance, a quick reading of Hepburn’s journal of her experiences working on the film is better than popcorn. This is how the professionals do it.

I’ll close with an excerpt from Hepburn’s book, and from the original novel:

It was during this pause that John came on morning to my hut.

“May I have a cup of coffee?”

“Yes, of course—what?”

“Well—I don’t want to influence you. But incidentally…that was great, that scene, burying Robert. And of course you had to look solemn—serious….Yes, of course—you were burying your brother. You were sad. But, you know, this is an odd tale—I mean, Rosie is almost always facing what is for her a serious situation. And she’s a pretty serious-minded lady. And I wondered—well—let me put it this way—have you by any chance seen any movies of—you know—newsreels—of Mrs. Roosevelt—those newsreels where she visited the soldiers in the hospitals?”

“Yes, John—yes—I saw one. Yes.”

“Do you remember, Katie dear, that lovely smile–?”

“Yes, John—yes—I do.”

“Well, I was wondering. You know, thinking ahead of our story. And thinking of your skinny little face—a lovely little face, dear. But skinny. And those famous hollow cheeks. And that turned-down mouth. You know—when you look serious—you do look rather—well, serious. And it just occurred to me—now, take Rosie—you know—you are a very religious—serious-minded—frustrated woman. Your brother is just dead. Well, now, Katie—you’re going to go through this whole adventure before the falls and before love raises its…Well, you know what I mean—solemn.

“Then I thought of how to remedy that. She’s used to handling strangers as her brother’s hostess. And you ‘put on’ a smile. Whatever the situation. Like Mrs. Roosevelt—she felt she was ugly—she thought she looked better smiling-so she…Chin up. The best is yet to come—onward ever onward….The society smile.”

A long pause.

“You mean—yes—I see. When I pour out the gin I—yes—yes—when I…”

“Well,” he said, getting up to go. He’d planted the seed. “Think it over…Perhaps it might be useful…”

He was gone.

I sat there. That is the goddamnedest best piece of direction I have ever heard. Now, let’s see….

Well, he’s just told me exactly how to play this part. Oh-h-h-h-h, lovely thought. Such fun. I was his from there on in.

He may have no common sense—he may be irresponsible and outrageous. But his is talented. He ain’t where he is for no reason. And you’d better watch him. And learn a few things.

–from Katherine Hepburn’s The Making of the African Queen

Rose was really alive for the first time in her life. She was not aware of it in her mind, although her body told her so when she stopped to listen. She had passed ten years in Central Africa, but she had not lived during those ten years. That mission station had been a dreary place. Rose had not read books of adventure which might have told her what an adventurous place tropical Africa was. Samuel was not an adventurous person—he had not even taken a missionary’s interest in botany or philology or entomology. He had tried drearily yet persistently to convert the heathen without enough success to maintain dinner-table conversation over so long a time as ten years. It had been his one interest in life…and it had therefore been Rose’s one interest—and a woefully small one at that….

Save for a very few officials, who conducted themselves towards the missionaries as soldiers and officials might be expected to act towards mere civilians of no standing and aliens to boot, Rose had seen no white men besides Allnutt…

And Samuel had not allowed Rose even to be interested in Allnutt’s visits. The letters that had come had all been for him, always, and Allnutt was a sinner who lived in unhallowed union with a Negress up at the mine. They had to give him food and hospitality when he came, and to bring into the family prayers a mention of their wish for his redemption, but that was all. Those ten years had been a period of heat-ridden monotony.

It was different enough now. There was a broad scheme of proceeding to the Lake and freeing it from the mastery of the Germans; that in itself was enough to keep anyone happy. And for detail to fill in the day there was the river, wide, mutable, always different. There could be no monotony on a river with its snags and mudbars, its bends and its backwaters, its eddies and its wakes. Perhaps those few days of active happiness were sufficient recompense to Rose for thirty-three years of passive misery.

–from C.S. Forester, The African Queen

Some background on the film from George Lucas’s Blockbusting, edited by Alex Ben Block and Lucy Autrey Wilson:

Columbia originally bough the 1935 C.S. Forester novel as a vehicle for Charles Laughton and Elsa Lancaster. Later, Warner Bros. bought it for Bette Davis and David Niven. It was offered to Bette Davis again in 1947, but due to the birth of her daughter that same year, she had to pull out. On tour with As You Like It for the theater guild (1950-51) Katherine Hepburn became interested and was ultimately cast. This was the first produced screenplay for critic James Agee, who suffered a heart attack while on the project. John Huston recruited novelist Peter Viertel to help him finish the script (and revise Allnutt’s dialogue after Bogart stumbled over the character’s Cockney accent). Producer Sam Spiegel paid dearly to get the cast he wanted and to meet Huston’s grandiose aspirations, which included shooting on location, even in extreme conditions. The director flew more than 25,000 miles scouting locations. He choose [sic] a camp near Biondo, on the Ruiki River, in what was then the Belgian Congo. Spiegel attempted to save money by doing without crew members whose duties overlapped those of other technicians and craftsmen. He would recruit locals or ask the stars to help out. Hepburn, for a time, doubled as the wardrobe mistress, while Bogart’s wife, Lauren Bacall, helped cook and set up camp. Filming in jungle conditions was no picnic, as cast and crew were required to fend off blood flukes, crocodiles, soldier ants, wild boars, stampeding elephants, poisonous snakes, malaria, and dysentery, all in equatorial heat….The steamer was authentic. The L/S Livingston had been a working vessel for forty years. Because of cramped quarters, parts of the boat were re-created on a large raft for close-ups. Bogart, too, for all his macho reputation, was none too keen to serve as a host to live leeches for one of the most memorably queasy scenes ever filmed. He preferred rubber leeches, but Huston called in a leech wrangler, who arrived in London with a tank full of the squirming bloodsuckers. They compromised by placing rubber leeches on Bogart and live leeches on the breeder’s chest for close-ups. Like Forester, the filmmakers also debated how The African Queen should end. Ultimately, the unlikeliest scenario was chosen, and it proved to be a crowd-pleasure….The boat used in The African Queen is now docked next to a Holiday Inn on Key Largo and has been added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

–text by Gary Dretzka

Available on YouTube? Yes, at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sYww7kEVQJo

Also available for rental at YouTube