“[Bill] Miner and his men, posing as prospectors, fled south on foot, with $17 and a bottle of kidney pills, pursued by a large posse, [Mounties from Calgary], and the B.C. Provincial Police.”

First, a caveat. Although this month’s review has nothing to do with Clint Eastwood, those of you out there who have either: a) never watched a Clint Eastwood western or b) never liked a Clint Eastwood western you have watched, please skip the next paragraph and go on to the remainder of this month’s review. Trust me, it’s better this way. No point in us getting into a possibly bitter debate in which we might both say things we’d regret later.

Good. Now that I’m speaking to the converted, I want to begin by saying that Philip Borsos’ 1983 film The Grey Fox is the best-looking post-50’s western I’ve seen outside of the Eastwood stable of classics that began with A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and ends with 1992’s Academy-award-winning Unforgiven (1992). I’m not sure exactly what it is that makes any given western look “authentic”, but there’s no confusing pseudo-westerns such as Lawrence Kasdan’s Silverado with the gritty, dust-covered, fly-infested, boomtown-waiting-to-go-bust, where’s-the-law, awesome-but-forbiddingly-landscaped, operatic “wonders-for-hogs” of the real “western canon” (no apologies to Harold Bloom). You also need the faces. Faces that you might find staring out at you from 100-year-old, sepia-toned photographs found in the ruins of an abandoned prairie farmhouse. Sergio Leone and Clint Eastwood almost always got it right. So does The Grey Fox. I’ve got a lot more to say about the why’s and how’s, but I’d like to welcome my other, non-Clint readers back first.

Hi! Good to have you back! It’s safe. Not another word about C.E. We’re talking about The Grey Fox, the best Canadian western ever made. It earns that distinction handily. The setting is magnificent—the Lower Mainland and the B.C. Interior around Kamloops. B.C. haven’t looked this good on the big screen since Robert Altman shot McCabe & Mrs. Miller in the mountains north of Vancouver back in 1971. And if you love the sight & sound of the old steam trains, The Grey Fox will bring tears to your eyes. For the rest of us, Frank Tidy’s incredible cinematography, tracking locomotives through the epic Interior wilderness, shows us what we’ve been missing. There’s a scene with a train and runaway horses that has the surreal beauty of an Alex Colville painting. And speaking of horses, no self-respecting western would be complete without sweeping shots of men (and women) on horseback in the mountains. Ask any horse-owning rural youngster: there’s no life like it. By the end of The Grey Fox, the average viewer probably wants nothing more than to saddle up, ride up into the hills, and wait for a train whistle to blow in the far valleys.

I also admire Borsos’ choice of story. As writers such as Rudy Wiebe, Farley Mowat, Guy Vanderhaeghe, and Bob Johnstone have been showing us for years, Canadian history is as rich as any country’s in extraordinary lives and incidents. The Grey Fox tells the true story of Bill Miner, an American fugitive who wound up robbing trains near Kamloops, and who disappeared without a trace after escaping from the B.C. Penitentiary.

Credited with coining the expression “Hands Up!”, Miner was not an exemplary character. He robbed his first stage coach in 1863, at the tender age of 16, and robbed 26 more over the next 18 years. Nicknamed “the Gentleman Bandit” by the Pinkerton Detective Agency, he was finally caught and sent to San Quentin. When he was released 33 years later, he was a tough old man with a very limited resume. He was also in the 20th Century. The times they had a-changed. Stage coaches were gone, the world was becoming electrified., and things like mechanical apple peelers were the wave of the future. After trying a legitimate stint in the Pacific coast oyster beds. Bill Miner went back to the only job he knew how to do well. Trains were bigger and faster than stage coaches (check out the look of wonder which crosses Miner’s face when he faces his first train, and the astonished “I think we’re being robbed!” of his first victims in the new age), but a true professional could always adapt.

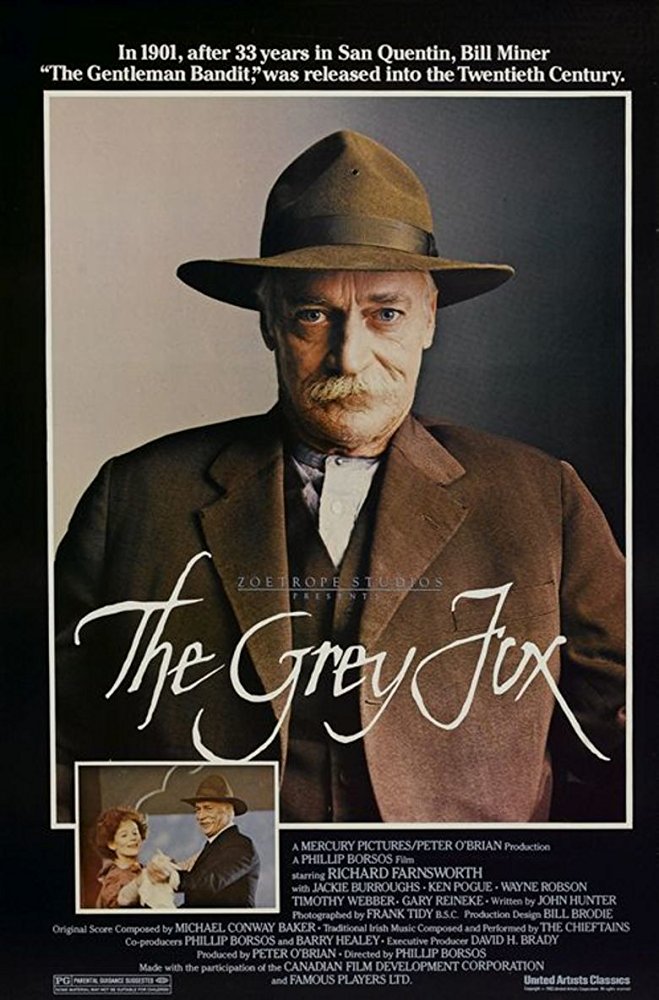

Actor Richard Farnsworth brings tremendous dignity to the role of Bill Miner. I still have a copy of the full- page close-up of Farnsworth that was used to advertise The Grey Fox at the Cannes Film Festival. How many films show us older men or women as models of strength, vitality, ambition, and confidence? As portrayed by Farnsworth, Miner had all of these qualities in spades. Perhaps it all rings so true because Richard Farnsworth himself had Miner’s grit. Starting out as a rodeo rider in the 1930’s, Farnsworth took the first of his 300-plus movie stunt jobs in 1938. At the age of 60, he embarked on a new (and successful) career as a full-fledged actor. The Grey Fox won him Canada’s Genie award for Best Actor, and an Academy Award nomination.

After a botched train robbery in Portland or Olympia, Bill Miner fled north into British Columbia. There he teamed up with an ill-assorted partner named William Dunn (“Shorty”–superbly played by Vancouver, actor Wayne Robson), aptly characterized as “short, dirty, nervous & unintelligent”. Shorty and Miner were after enough of a grubstake to buy them a securely anonymous retirement in Montreal.

The entire supporting cast of the film is impressive. In another part of the story, Miner forms an interesting liaison with a local Kamloops photographer named Catherine Flynn (Jackie Burroughs). An outspoken suffragette (“you’re not taken seriously unless you’re Caucasian, Protestant, and male”) Flynn is attracted to Miner by the pride and independence I described earlier.

A final “note” on the musical score–wow! Picture a locomotive steaming through twilit mountains to haunting, traditional Celtic music by The Chieftains. ‘Nuff said??

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Sex appeal has nothing to do with age. Most of us know or have known men or women in their sixties and seventies and beyond with charisma to burn. A part of their appeal is often the way they connect the rest of us to an older generation whose spunk and resourcefulness we respect and admire. The glory may at times be a bit ragged, but it’s glory nonetheless. Witness the cast of Netflix’s Grace and Frankie, and the undiminished star power of Dolly Parton, Willie Nelson, Charles Bukowski, and Leonard Cohen. The Grey Fox’s Richard Farnsworth reminds me of that Sixties poster that showed a bare-torso’d, ripped septuagenarian under the header “Growing Old is not for Sissies.” Farnsworth’s character, Bill Miner, can’t hold down a real job, and there’s absolutely nothing heroic about his life of crime. But despite having spent half of his life in San Quentin and being cast out into a new world that doesn’t owe him a thing, he can hold on to his dignity. Small wonder that Kate Flynn, herself an outsider in Kamloops because of her feminist politics and contrariness, falls for him. I loved Roger Ebert’s description of his reaction to the dawn of a new century as “confused but interested.”

Sadly, leukemia claimed the life of director Phillip Borsos in 1995, at age 41. Cinematographer Frank Tidy went on to work on another forty films until his retirement in 2004. Richard Farnsworth worked in film and television until his death in 2000 at age 80. Jackie Burroughs did the same until her death in 2010 at age 71.

This may not be the Great Canadian Western, but it’s a damn good one. Happy trails, you old rogue.

If you have the chance, check out the reviews of The Grey Fox by Roger Ebert, Jay Scott, and Pauline Kael. It’s a testimony to the film’s quality that it appealed to all three critics.