“When a good child dies, an angel comes down from heaven and takes the dead child in his arms; then the angel spreads out his wings and flies with the child to visit all the places that the little one has loved. They pick a whole armful of flowers and bring them to God; in heaven, these flowers will bloom even more beautifully than they have on earth. God presses all the flowers to His heart; but the one that is dearest to Him, He gives a kiss, and then that flower can sing and join in the hosanna.”

—Hans Christian Anderson. “The Angel”

I, the LORD God, gave your sister a large, deep cup filled with my anger. And when you drink from that cup, you will be mocked and insulted. You will end up drunk and devastated, because that cup is filled with horror and ruin.

—Ezekiel 23:32-34, Contemporary English Version

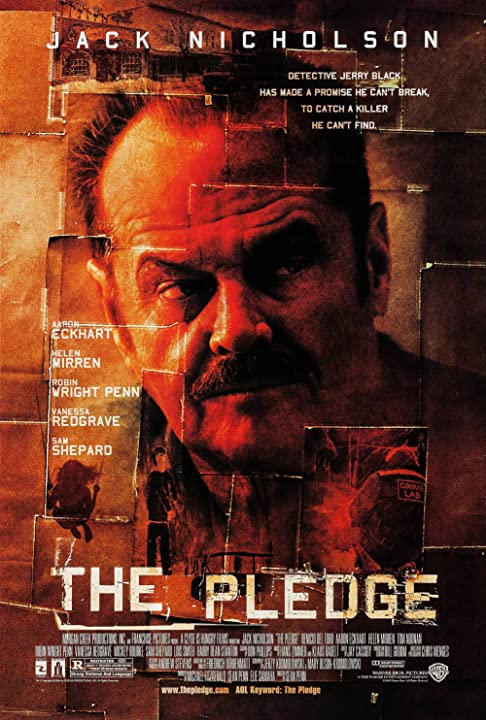

I don’t know if I have ever used the word “devastating” to describe a film, but I can think of no better description for Sean Penn’s The Pledge (2000). As gifted a director as he is an actor, The Pledge is his third film (the first was Indian Runner in 1991; the second The Crossing Guard in 1995)—and his strongest. The challenge in writing about it is to say enough to give you a sense of this movie’s power, without betraying its secrets.

At first glance, the storyline seems similar to dozens that one might encounter in other films or on television. A veteran detective with a lifetime of solid police work behind him takes on a final case hours before his scheduled retirement. The role of the detective, Jerry Black, is played by Jack Nicholson. It’s one of his most understated, finest performances. When none of the local police want to take on the responsibility of telling the parents that their seven-year-old daughter has been raped and left to die in the snow on the edge of a forest bordering a frozen lake, Jerry volunteers to go out to their farm.

Coming on the heels of a disquieting opening sequence, and the bleak scenes of the discovery of the girl’s body, Jerry’s visit to the farm also begins in an almost surreal manner—he delivers the heartbreaking news in a huge barn filled with a sea of thousands of young turkeys. Seconds before Jerry walks into the barn, the wife holds up the body of a dead turkey. Nothing is as it should be. Omens and portents. Sean Penn will show that he is able to chill the viewer’s heart as subtly yet irrevocably as frostbite takes hold of the traveler who finds no shelter from the storm.

Jerry promises the Larsens that he will find their daughter’s killer. Margaret Larsen (Patricia Clarkson) isn’t satisfied. She takes a small wooden crucifix made by her daughter and demands that Jerry reaffirm his pledge on his soul’s salvation. Both demand and assent are a bit creepy, but it’s all easy to explain away as the understandable desperation of distraught, bereaving parents and the conscientiousness of a good cop.

At first, it seems that the pledge will find short shrift. A mentally challenged Indian trapper with a history of petty crime and a conviction for statutory rape is ID’d by a witness. The trapper (a short, powerful performance by Benicio Del Toro, one of several strong cameos by actors such as Harry Dean Stanton, Mickey Rourke, Helen Mirren, Vanessa Redgrave, Sam Shepard, and Tom Noonan) confesses during a disquietingly intimate interrogation, and while being taken back to a holding cell grabs a policeman’s revolver and kills himself.

Case closed. For everyone except Jerry.

Jerry senses there’s something seriously wrong with the whole scenario everyone else has so eagerly accepted. He gives up the expensive marlin fishing vacation his colleagues have bought him for the beginning of his retirement, and starts digging. He finds two virtually identical cases of very young girls—the same age as the Larsens’ daughter, wearing the same kind of red dress—killed or disappeared in the same county in the previous eight years. The locations of all three crimes plot out on a map in an obvious circle.

Jerry takes his findings to his former colleagues. They dismiss them as coincidence. Why muddy an open-and-shut case? The Larsens are getting on with their lives; it’s time Jerry got on with his.

The Pledge should have been very predictable from this point on: Jerry heroically fulfills his vow by ignoring his cynical police buddies and single-handedly tracking down the psycho responsible for the three girls’ deaths. That’s the way catharsis works: tragedy, quest, vengeance, and satisfaction. A plotline as old as history.

Not this time.

For each person who cares enough about The Pledge to watch it closely, there will be a sinister epiphany. A moment when one realizes that something in this moral universe is badly awry. When that moment comes, the effect is like that described in Emily Dickinson’s lines about “a tighter breathing/and Zero at the Bone.” From that moment on, the viewer is set adrift—uneasy, fearful, and wondering. A time of Voices and Visions.

Penn makes ironic, effective use of very real landscape to reinforce the sense of unreality. Shot mainly around Keremeos, Lytton and Merritt, the film’s mountains, lakes, and rivers are symbols of permanence and eternity, sharply contrasting with Jerry Black’s harrowing quest for a serial killer only he believes in. Jerry’s own house is built on sand—for the last few years of his career as a cop he’s been pitied as an alcoholic and a clown, a good man broken by a surfeit of horror, failed marriages, and loneliness. His only hobby is angling, another solitary pastime. It brings him no peace.

Again, nothing is as it should be. Jerry’s hours on the lake should be a kind of redemption. They should be healing. So should the relationship that Jerry strikes up with Lori (Robin Wright Penn) and her seven-year-old daughter, Chrissy. Lori is a roadside waitress, a gun-shy survivor on the run from an abusive husband. She finds in Jerrv a man who seems able to shelter her and her child with no strings attached—a reclusive ex-cop who seems interested only in angling, the old garage he’s purchased, and reading bedtime stories to Chrissy. Lori knows nothing about Jerry’s pledge. She doesn’t know that the only reason he spent his life savings on that garage, the only reason lie’s living in her remote logging community, is to set a trap for a killer of girls tike h«r own.

Perhaps The Pledge should not have surprised me as much as it did. The opening credits acknowledge that the story is based on a book by Swiss novelist and dramatist Friedrich Dürrenmatt. Durrenmatt is best known here in North America for a series of macabre and frightening dramas that includes The Visit, The Physicists, and An Angel Comes to Babylon. It’s hardly surprising that when Dürrenmatt turned his attention to the detective novel in the 1950s he found more inspiration in Franz Kafka than Agatha Christie. In stories such as Traps, The Quarry, The Judge and His Hangman, and The Pledge Durrenmatt wove skeins of crime, guilt and paradox. To the viewer’s discomfort and dismay, Sean Penn, Academy-Award-winning Director of Photography Chris Menges, and Musical Directors Hans Zimmer and Klaus do full justice to Dürrenmatt’s vision. In Durrenmatt’s own words, here are some of the operating principles of the “new” detective story, taken from his 21-point epilogue to The Physicists:

-A story has been thought to its conclusion when it has taken its worst possible turn.

-The worst possible turn is not foreseeable. It occurs by accident.

-The more human beings proceed by plan the more effectively they may be hit by accident.

-Such a story, though it is grotesque, is not absurd.

Hercule Poirot and Nero Wolfe fans beware.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

This has happened to me before. I start watching a film I’ve reviewed a long time ago, and after fifteen minutes I’m wondering why on earth I would have ever thought this particular film was worth a column. About halfway through the film, I start to clue in. By the time the closing credits roll, I’m giving myself a high five. Sean Penn’s The Pledge starts out as the kind of crime drama with which those of us with Netflix and other streaming accounts are comfortable. I’m talking about Midsomer Murders, Father Brown, Poirot, Wallander, Shetland, Vera, The Bridge, Elementary, and many, many others. All excellent in their own way. At a certain point in The Pledge, however, one senses that there may be something seriously wrong with one’s assumptions. Uneasy suspicions surface. And by the time one reaches the devastating conclusion, the tragic turn is as profound as that at the end of Chinatown. Sometimes the good guys lose. Everything.

What caused me to doubt myself in the opening scenes, before the darkness starts to fall? The first thing was the cast—there were so many standout actors in minor roles (Benicio Del Toro, Helen Mirren, Vanessa Redgrave, Mickey Rourke, Sam Shepard, Harry Dean Stanton) that I found myself distracted by the star power. It seemed like overkill. If I were to guess, I’d say that some of this casting was decided on the basis of how valuable it would be in attracting financing for the picture. Or perhaps, just as likely, they were simply happy to work with a director whose talents they admired. I don’t fault them for their contributions to The Pledge, but I’d have been happier with a supporting cast of relative unknowns.

The second distraction was the choice of location shooting. It looked like my back yard, and it almost was. Most of The Pledge was shot in the southern interior of British Columbia, a couple of hundred miles east of my home in the Kootenays. During my university years in Vancouver, the Greyhound bus linked my parents’ home in Castlegar with many of the key settings in the film—Hope, Chilliwack, Keremeos, Princeton, Hedley. Some of those bus stops are permanently imprinted on my memory. For a while, it was hard to shake off those memories as I was watching The Pledge. Not Sean Penn’s fault, of course.

The last distraction, and for me still the most serious, is being forced to wonder why Benicio Del Torres was cast as a Native American. Really, no Indian actors were available? I’d expect to see this kind of casting choice in a film from the 1940s or 1950s, not from the 21st century. I’d say there might be a perfectly good explanation if I wasn’t damn sure that there isn’t. Somebody prove me wrong, please.

In the end, of course, the arc of the story carries all before it. There are reasons Roger Ebert included The Pledge among his choice of Great Movies, no small honor that. As Ebert said, “This film hasn’t been about murder but about need….All of [Sean Penn’s] films show a man determined to prove something, at whatever cost. He is not proving it to others. He is proving it to himself.” The price paid is what separates pathos from tragedy. Most crime dramas are strong on pathos; few impress as tragedy. The last show that did this for me was the Mags Bennett storyline in the second season of Justified (2011). Catharsis is hell.

P.S. Robin Wright has been nominated for 8 Primetime Emmys. I’d say she’s due for a win. Composer Hans Zimmer has currently has ten Oscar nominations, but at least he’s gotten to take one home. And he’s probably pretty happy with his 140 other awards and 270 other nominations.

Available on YouTube?

No, but available for purchase or rental through YouTube & iTunes