“It is not my place to be curious about such matters.

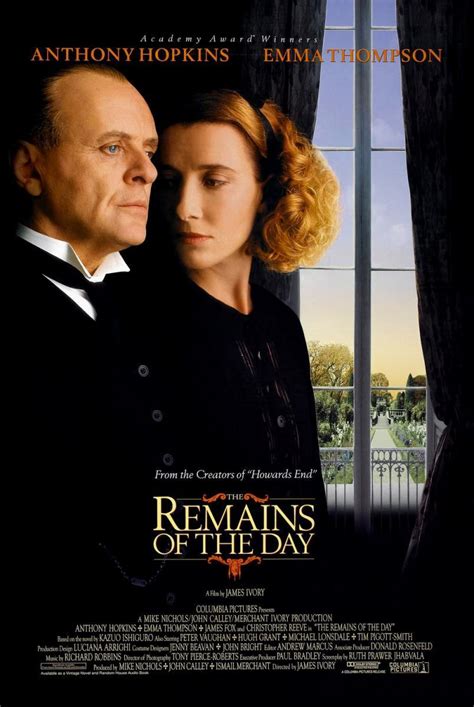

Imagine a powerfully romantic film where the lead actors never once kiss, hold hands, or address one another by their first names. Imagine lives being ruined because one man acts selflessly and honorably, and another strives for peace and reconciliation. Imagine a lead actor nominated for a dozen critical awards for a role in which his most extravagant gesture is a touch on the shoulder or the laying down of a silver tray, and his voice is never raised in passion, anger, or despair. The Remains of the Day (1993), directed by James Ivory from a screenplay by his longtime collaborator Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, is something of a miracle.

Jhabvala based her screenplay on the Booker Prize-winning novel of the same name by Kazuo Ishiguro. The story, in the form of a 250-page interior monologue, was initially thought to be unfilmable. How could such a monologue—modulated on a tone of repressively controlled introspection that never breaks into self-pity or recrimination—be made cinematic? The great English playwright Harold Pinter made one attempt and failed. Prior to being given another chance, Jhabvala already had an impressive track record in making great literature work on the screen. She’d done amazing work with adaptations of E.M. Foster’s A Room with a View and Howards End. The Remains of the Day perhaps added a touch of cultural alchemy with a 66-year-old German writer of Jewish background living in Delhi and New York with her Indian husband, reshaping a story by a 39-year-old Japanese writer educated and living in England. The script for The Remains of the Day is as fine an example of the screenwriter’s art as one is likely to find. Another real strength of the script (and of James Ivory’s direction) is the flawless movement back and forth between flashbacks to the Thirties and the narrative present of the 1950s

The Remains of the Day is the portrait of a singular man—James Stevens, Butler of Darlington House. Darlington House is the kind of upper-crust mansion where the hounds are often on the hunt, the silver is always polished, and the Head Butler and Head Housekeeper are only slightly less infallible than God. Lord Darlington, the head of Darlington House, is fully aware of the superb quality of his staff. He inspires Stevens’ devotion by incarnating the noble virtues that Stevens expects of a man worthy of unquestioning service. In Stevens’ own words to an old friend, “In my philosophy, Mr. Benn, a man cannot call himself well-contented until he has done all he can to be of service to his employer. Of course, this assumes that one’s employer is a superior person, not only in rank, or wealth, but in moral stature.”

Anthony Hopkin’s portrayal of Mr. Stevens is one of the movies’ great masterpieces of understatement. Here is a consummate actor who needs no more than the stoop of a shoulder, a hesitation of voice, or slight tremor of facial muscles to capture the full tragedy of a man’s life. The dropping of a wine bottle is as dramatic as a death. How ironic that Hopkins should have won an Academy Award for the over-the-top malignancy of Hannibal Lecteur, and been bypassed by the Academy for his most masterful performance. Hopkins is helped significantly by a key change in focus Ruth Jhabvala made from the original novel. In the book, the relationship of Stevens to the Housekeeper, Miss Sally Kenton, was secondary to the house’s political intrigues. The screenplay reverses these. Hopkins and Emma Thompson, as Sally Kenton, play off one another superbly. The great error in Stevens’ life is not in blindly serving a master who is ultimately revealed to have feet of clay; it’s in not having the courage to let love penetrate the austere walls of duty.

Emma Thompson’s Miss Kenton is a rich blend of strength and vulnerability. Much younger, she’s every bit Stevens’ match as an administrator. Her vulnerability comes from having reached an age, thirty or so, when having no family of any kind to fall back upon—or look forward to—casts a pall of loneliness upon her future. Unlike Stevens, she cannot cling solely to the ideal of service. She knows that as Stevens’ wife she would have both the family life she desperately wants and a challenging job commensurate with her skills. Stevens’ response is flight. A life without “distractions.” Hopkins perfectly conveys the terrible price his fixation on duty is exacting. This is one of the most achingly unconsummated relationships ever brought to the screen. As critic James Berardinelli said, it’s “tragedy without catharsis.” The scene where Sally Kenton catches Stevens reading a sentimental romance in his study (a book he immediately dismisses as a generic tool used in the furtherance of his “command and knowledge of the English language”) I replayed three times—like one of those gorgeous bits of music you just can’t let go. The Pachelbel’s Canon of movie love scenes. And then there is the ineffable beauty of the scene where Kenton stands forlornly in the back of a bus, as night closes down and rain falls, Stevens losing her for the second time and forever.

The film’s second tragedy is that of Stevens’ master, Lord Darlington. Darlington sees himself as a peacemaker, a diplomat, the perfect host to the cream of English, French, and German society. It’s the last bit that’s the problem. This is 1936 and the cream of German society he’s hosting are members of the 1000-year Reich. The cream of English society are anti-democrats and Nazi sympathizers. Behind his back, the former size up Darlington’s house as a potential source of looted art; the latter treat men like Stevens as part of the unwashed ignorant rabble who have no business interfering in the running of world affairs by superior beings such as themselves. There is a lot of talk on all sides of Germany’s “virile” struggle for economic recovery (“They’ve gotten rid of all that trade union rubbish—believe me, no workers strike in Germany!”) and its “sanitary” racial laws. Lord Darlington himself is not evil. He has earned Stevens’ loyalty, not just inherited it. But at this historical nexus he’s also a fool and a dupe. A poodle in a pool of sharks. Seeking to correct the very real injustices of the Treaty of Versailles hammered out by the Allies at the end of the First World War, Darlington has no idea that the Germany he’s championing has been making Faustian deals with the devil.

He dutifully reads the anti-Semitic literature passed on to him by his visitors. He dismisses two Jewish servants lest his guests be made “uncomfortable.” He brings together the architects of the appeasement policy that will sacrifice Czechoslovakia to the interests of a “greater good.” He knows something is very wrong, yet he can’t understand how following the ideals by which he’s lived his whole life can foster evil. After the war, in a quixotic gesture worthy of Oscar Wilde, he sues a newspaper for libel and ends up with his family’s reputation destroyed and himself condemned in the public eye as a quisling for the Nazis. When Stevens takes his first vacation from Darlington House, long after its owner’s death, he finds himself in the role of Peter the Apostle—denying all knowledge of his master when questioned about his past in a country pub. Later he will make the same denial to a journalist who gives him a lift, only to recant and assert that whatever Darlington’s mistakes had been he was an honorable man whom he’d been proud to serve.

Along with being a tour de force of acting (including supporting roles by Christopher Reeve, Hug Grant, and Peter Vaughan) and screenwriting, The Remains of the Day is also noteworthy for Tony Pierce-Robert’s elegant cinematography, for the minimalist musical score by Richard Robbins, and for James Ivory’s use of on-location filming. Darlington House is actually a cinematic illusion—a composite of several different real-life locations. Exteriors were shot at Dyrham Park, built in the 18th century. Some interior shots were done at 600-year-old Powderham Castle, near Exeter. Other interiors were shot at Corsham Court in Wiltshire and Badminton House in Gloucestershire. Ivory’s skill in making of these disparate settings a single fictional one is in its own way as subtle a performance as Anthony Hopkins’ benighted Mr. Stevens.

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

“I’m certain his Lordship is acting from the highest and noblest motives.”

–Head Butler Stevens, describing his employer, Lord Darlington

Still absolutely one of my favorite films. Great performances. Superb cinematography. Masterful control of time between present time and flashbacks, impeccable period production design. Tragedy on multiple levels. Blind faith. Betrayal of one’s self and one’s nation. Honor & Shame. Collaboration & Appeasement vs. Arrogance & Duplicity. Duty vs. Joy.

How was it possible for The Remains of the Day to be nominated for 8 Oscars and not win any? A sad night in Hollywood, that one.

Three things that struck me this time around were Miss Kenton’s avowal of her own cowardice & vulnerability in not resigning over the dismissal of the two Jewish refugee girls, the incredible intimacy between Miss Kenton and Stevens in the scene where she insists that he show her the book he is reading, and the way one of the German “guests” eyed Darlington Hall’s artworks and told his subordinate to note them down “for later.” The first instance was just one of the many, many moments Stevens had to do the right thing…and didn’t.

A question: Is one of the books we see Lord Darlington reading so assiduously Mein Kampf?

One thing I’d like to know more about: the English “black shirts” and the British Union of Fascists.

My ideal for a heartbreaker double-bill: The Remains of the Day and Raise the Red Lantern.

I know that there really was, and still is, a world where servants iron newspapers for their masters, but that doesn’t make it any easier to believe or to stomach. This isn’t how the other half lives; it’s how the tiny handful of people who control the world’s wealth live.

Christopher Reeve, in his role as the sharp-eyed American intruder into the incestuous German/British aristocracy of condescension and contempt, shows the U.S. in the best realpolitik light. But we shouldn’t lose track of the fact that America had its own fascist movement and its craven appeasers. Check out Thomas Doherty’s Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939 and Ben Urwand’s The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler.

At this point, however, I have to apologize for the incompleteness of this review. I’m unable to recommend any follow-up readings on the history of pro-German fascists movements in the decades between the two World Wars. I’ve also lost touch with Merchant-Ivory films over the years, and need to make up for that lapse. It’s going to take time. I have a lot of catching up to do. Most shameful of all, I still haven’t read any of Kazuo Ishiguro’s work beyond The Remains of the Day. Not a deliberate slight, by any means. I’ve just picked up a copy of Klara and the Sun.

For someone who enjoys reading the novels on which movies are based, the Merchant-Ivory films present a formidable challenge: Henry James, Kazuo Ishiguro, E.M. Forster, Jean Rhys, and several other fine writers. Yeesh! It’s like cinema’s version of Britannica’s Great Books series.

Fans of the work of James Ivory, Ismail Merchant, and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala will also want to check out the merchantivory.com website.

Available on YouTube? No, but available for rental or purchase through YouTube & iTunes