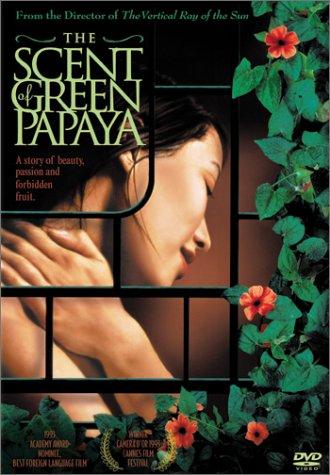

The Scent of Green Papaya (1993), by the Vietnamese director Tran Anh Hung, and the first Vietnamese film to be released in the U.S., is the cinematic equivalent of a Japanese bonsai. Just as a bonsai tree manages to capture the beauty and depth of its real-life model on a breathtakingly reduced scale, The Scent of Green Papaya recreates in meticulous detail, on a Paris sound stage, life in a single home on the corner of a street in Saigon. This is a telescoped vision where an extreme close-up of a young boy’s hand, grazing the tears on his mother’s bare foot, becomes the essence of tragedy.

The time is 1951. A young girl, Mui, has been sent by her parents to work as a servant in a merchant’s household in Saigon. She is taught the necessary skills by a sympathetic older servant (Anh Hoah Nguyen). Both the mother (Thi Loc Truong) of the household and the mother-in-law are drawn to her because she resembles the daughter they had lost a few years previously. The household is not a tranquil one. The husband is a gambler and a womanizer who periodically takes all of the family’s money and disappears. The mother-in-law blames the wife for her son’s failures. The two younger sons can make no sense of the abrupt dislocation of their lives; an older son has made his peace by moving out on his own.

Had anyone else made this movie, it might have turned out as a Balzacian tragedy or a Marxist morality play. Balzac himself would have seen the opportunity for another Père Goriot; Marx would have reveled in another opportunity to slam capitalist callousness. The ingredients are all there: a decadent bourgeois household, family conflict, a naive servant girl ripe for exploitation and abuse. Surely there is an inevitability in the telling of such a story?

Hardly. Tran Anh Hung has crafted a tale of Zen Buddhist-like calm, focus and simplicity. Sounds (a cricket, footsteps, rain) become as important as dialogue. I cannot think of a single other contemporary film which unfolds with such a sense of inner peace. “Serene” seems an impossible word for a modern critic. Even in recent films remarkable for their artistry, such as Jane Campion’s The Piano and Zhang Yimou’s Raise the Red Lantern, the plot hinges on moments of intense passion and violence. The Scent of Green Papaya offers no such catharsis, and some disgruntled critics harped on its absence. They dismissed the film as a paean to “spirituality through servitude,” or as a male fantasy rooted in a disgraced tradition of female silence and compliance. I prefer to celebrate this film for what it is rather than what it might have been. In Japanese there is a common expression, Shikata ga nai, which translates loosely as “It can’t be helped. Oh, well. Too bad.” Victory through acceptance. You can choose to lament what has been lost, or embrace what you have. Far, far easier said than done. Like the song says, most of us would rather be the hammer than the nail. That’s certainly true of most directors and the way they handle stories like this one.

Along with Hung’s unique perspective, much of the credit for the success of The Scent of Green Papaya must go to the fine performance of Lu Man San as the 10-year-old Mui. She effortlessly negotiates her new life, learning what must be learned, endlessly fascinated by the smallest details of her surroundings, untouched by the youngest son’s petty torments or the household’s greater tragedies. Her radiant smile never fades, and her eyes never cease to search out the miniature lives of insects, the flow of sap from a severed papaya stem, the intricate whorls of silver on a family heirloom. This is a life where the simple act of stir-frying vegetables becomes consequential; the storms of life are as powerless against Mui as the demons were against the Buddha as he sat beneath the Tree of Enlightenment.

In a film full of such gifts, Anh Hung Tran’s last to Mui, now a radiant 20-year-old bride-to-be (Nu Yên-Khê Tran), is a spiritual one: her lover teaching her to read.

Sidebar #74e: Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Given that cinema as an art form was invented to be shown in darkened rooms, one might think that there are a lot of films that take advantage of that darkness to tell quiet, intimate stories that gently treat the eyes and touch the heart. Well, not so much. Productions have always leaned much more towards Sound & Fury. Even more so now that we’re living in the Marvel Comic Universe.

So, when finally one does come across a well-crafted film that is unabashedly quiet and intimate, one is very, very grateful.

The Scent of Green Papaya is a perfect example of such a film. Although there’s tragedy here, there’s no fury. The sounds are those of birds, crickets, frogs, a tiny gong, a Chopin-esque piano. A breaking vase shatters the silence for a moment, but only for a moment. The setting is on the smallest scale possible, compressed, as if the audience is looking into a dollhouse that’s suddenly become animated with people doing daily chores, suffering small & large wounds, falling in love and coping with loss. The dollhouse feeling is intensified by Benoît Delhomme’s camera that seems to be perpetually looking at characters through doorways, windows, arches, screens, and railings. This is filmmaking the way Chekhov might have approached had he been around in the 20th century, and been in an optimistic mood.

Man San Lu is perfection as the 10-year-old Mui, communicating both a beguiling charm and an inner strength. These qualities are also embodied by Nu Yên-Khê Tran as Mui at age 20. Tran’s smile at the close of the film is the blossoming of the spirit we saw at the beginning. Although the occasional external sounds of aircraft are deliberate reminders of another Vietnam (the film’s timeframe extends across both the First Indochina War and the Vietnam War), director/writer Anh Hung Tran isn’t interested in scoring points by playing the heavy. Fate is as often kind as it is cruel.

If happy endings aren’t your thing, and you’re looking for the Shadow side, you can always double bill The Scent of Green Papaya with Yimou Zhang’s Raise the Red Lantern. Songs of innocence, Songs of Experience.

Kudos to composer Tiêt Tôn-Thât for his understated score.

Benoît Delhomme has gone on to a rich career as a Director of Photography. He was working on three films in 2020, thirty-six years after his debut short film in 1984. Anh Hung Trans has made five films since The Scent of Green Papaya, his last in 2016. Nu Yên-Khê Tran has made half a dozen films. This was Ma San Lu’s only film.

NOTE: The YouTube version of the film I’ve linked above has excellent video quality and good English subtitling. The only glitch is that the subtitles remain on the screen until they’re replaced by new ones. A minor fault I can live with.