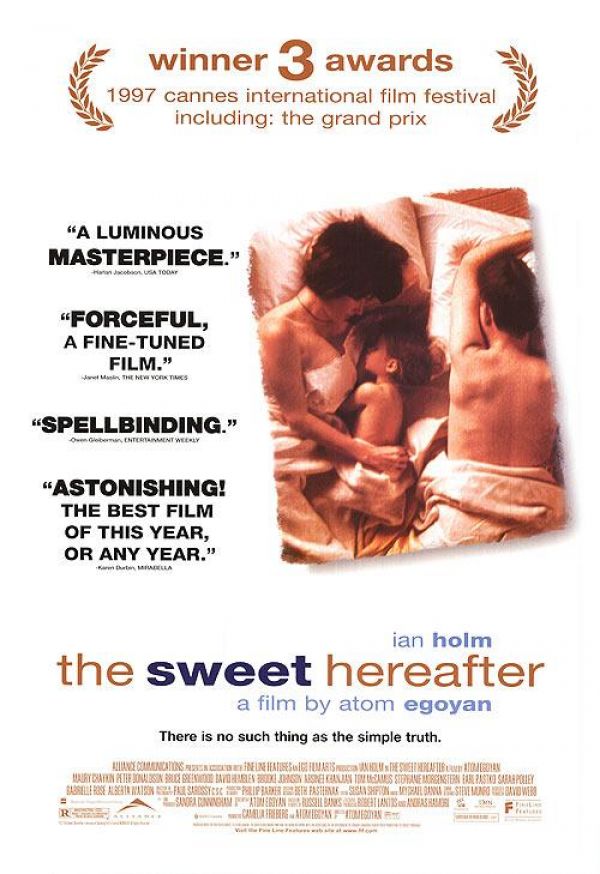

Eat crow, Panio. You rented Atom Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter (1997) in order to bury him, and instead you’re forced to spend this entire column praising him. It’s so unfair. Whatever happened to the old Atom, the director who was so sure of his omniscience that he fixed all his characters in elegant cinematic phrases and pinned them, sprawling and wriggling—more desperate than T.S. Eliot’s Prufrock—on movie screens across the world. He was so easy to mock. His actors were a means to an end, and the end was like arriving home to find one’s house empty and the walls stripped bare.

I expected The Sweet Hereafter to be more of the same. I rented it out of a sense of obligation. Who was I to ignore a Canadian film that had garnered praise around the world? After all, I could watch it, dismiss it, and go on to better things. Like Lost in Space or My Favorite Martian.

Ooops. Despite my best efforts at denial, it took me all of ten minutes to start to realize that The Sweet Hereafter was one of the finest Canadian films I had ever seen. Heck, it was one of the very best films I had ever seen, period. Halfway through, I was anticipating the pleasure of watching it a second time. Light years away from being mere puppets in the hands of Egoyan the Auteur, each of the characters in The Sweet Hereafter radiates her or his humanity with the kind of force and depth and absolute integrity I associate with the novels I’ve most admired. Every performance in The Sweet Hereafter, regardless of screen time, is memorable. Amazing what filmmakers can do when they place this much trust in their actors. Everything else in this film—the editing by Susan Shipton which seamlessly flows the story between the present time and three different pasts, the musical score by Mychael Danna, the superb cinematography by Paul Sarossy—exalts the actors’ work.

Ironically, even what I’d consider Egoyan’s weaknesses in the past become strengths here. Instead of breeding an intellectual sterility, his ability to reduce backgrounds to stark essentials works in The Sweet Hereafter to heighten the overwhelming sense of loss each character feels. I doubt there is another director who could have made that fatal school bus look more haunting, or turned those motel rooms and living rooms and other settings where people come to terms with their loss and anger into more perfect stages for their tragedies.

And tragedies they are. A small town loses twenty of its children when a school bus slides off an icy winter road and drops through the ice of a frozen lake. A big-city lawyer (Ian Holm) comes to the town to help the grieving parents launch a legal holy war against faceless bureaucrats whose greed for profit he claims must have been responsible for the accident.

The parents of the children who died fight their own battles. Some, like motel owners Wendell (Maury Chaykin) and Risa Walker (Alberta Watson), hope to use the law to exercise the kind of power they could never before have dreamed of having. Others, like Wanda (Arsinée Khanjian, Egoyan’s wife) and Hartley Otto (Earl Pastko), let their grief be turned to rage. Billy Ansell (Bruce Greenwood), who had lost his wife to cancer and clung to his two young children as his only connection to any kind of life that made sense, just wants closure. He insists that blame is meaningless, and the law only an instrument to turn neighbor against neighbor in a nightmare of suits and counter-suits.

The one child who survives the accident, paralyzed from the waist down, carries not one but two massive burdens. The lightest is the trauma of the accident itself. The heavier is a father who has stolen her childhood through an incestuous fantasy. The role of Nicole Burnell made the young actress Sarah Polley a star. No surprise. It’s a superb performance. Want to know why we need more poetry read aloud? Listen to Ms. Folley reading Robert Browning’s “The Pied Piper of Hamelin.” At first a simple bedtime story for Billy Ansell’s children, by the film’s end it becomes an uncanny parable of both despair and hope. The fate of the small town in which she lives falls into her hands. She will deliver them from one evil, as her accident has delivered her from another.

Dolores Driscoll (Gabrielle Rose), the driver of the fatal bus, lives out a never-ending Judgment Day. For Dolores the bus was a great wave that has broken and washed away all their lives. Childless herself, she’d seen the children she picked up every day like a more optimistic Catcher in the Rye: “bright little clusters of three and four children, like berries waiting to be plucked…[it was] like I was putting them into my big basket.” Her living room wall is covered with their photographs. She doesn’t take them down. Eventually she will reconcile herself to her own innocence, and carry the uncertain weight of judgment of the people of her town.

Last but not least is the lawyer, Mitchell Stephens, who comes to town to beat the ploughshares of grief into the swords of litigation. He is, to use David Richard Adams’ memorable phrase, one of “those who hunt the wounded down.” In his world there are no accidents. There are only victims and those who must be made to bleed for the damage they’ve caused. It doesn’t help that Stephens himself is among the wounded being hunted down. His own daughter Zoe (Caerthan Banks) is a drug addict who for ten years has bled his heart dry. Because he cannot understand how his daughter was lost to him, he clings to the belief that there’s something evil out in the world which is stealing children away. He’s blind to the fact that he himself might have become an agent of that evil.

Stephens’ most telling comment is one he makes to a young woman, Mary (Brooke Johnson), an old friend of his daughter from the days when friendship was still possible. He tells Mary how he’d once almost had to perform an emergency tracheotomy on the then 3-year-old Zoe, when she’d been bitten by baby black widow spiders. They’d barely made it to the hospital on time. Stephens tells Mary, “I did not have to go as far as I was prepared to go…but I was prepared to go all the way.” Twenty years later, he’s still prepared to go all the way. But in what cause? Ian Holm did not receive an Academy Award nomination for this performance. He didn’t even get a Genie. The only Genie The Sweet Hereafter did get was “Best Overall Sound”. It makes you wonder, doesn’t it?

By the way, if you’re reading this I really need your help. I’m frustrated. I can’t do the quality of the performances in the movie justice. You’ve got to see them for yourself. If you’ve already watched it once, watch it again. Check out the hesitancies in Ian Holm’s conversations with his daughter, Billy Ansell’s expression as he watches the bus carrying his children slide off the road in front of him, Hartley Otto’s silent embracing of his wife as her heart freezes over, and Dolores’ voice as she calls up, needlessly for the purposes of the deposition she is giving but imperative for her own healing, the names of each of the children who died on her bus.

There’s something else which should draw you back to The Sweet Hereafter: the sense of hope that lingers at the end. There is no shame in being destroyed by tragedies such as these. They are soul-shattering. Some of us will break and will surrender. But there is also no shame in survival. Nicole and Dolores come to understand this. Nicole’s closing narration is both epitaph and promise:

“We’re all citizens of a different town now—a place with its own special rules and its own special laws. A town of people living in The Sweet Hereafter…

Where waters gushed and fruit trees grew

And flowers put forth fairer hue

And everything was strange and new

Everything was strange and new.”

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

My original intention here was to do a retrospective of Atom Egoyan’s films, all of which are now available through iTunes. I watched or re-watched half a dozen films, and downloaded others. In the end, I wound up writing the retrospective for my Seldom Scene column in the August 2020 issue of the East Shore Mainstreet. Some day it may show up on this website. Only a couple of decades to go….

So all that’s left for me here is to say that The Sweet Hereafter remains my favorite Egoyan film, in spite of the masterful work he’s done over the past couple of decades. I can think of no more powerful portrayal of loss, grief, longing, and strength in adversity. Hereafter is a perfect example of the art of adapting a novel to the screen, both in terms of the new elements the screenplay introduced and in the way that the screenplay abandoned or ignored key elements of the book. Ironically, what was added—Sarah Polley’s reading of the Pied Piper story—was a purely literary element that became cinematically haunting. Another inspired addition was that of Mitchell Stephens’ with a former friend of his estranged daughter—a young woman who has grown up to be everything his own daughter has thrown away. One of the key elements left out of the film—the book’s climax at a demolition derby—was superficially the most kinetic plot element from the point of view of visual impact. Hereafter is possibly Atom Egoyan’s least convoluted narrative, alternating only between the time period immediately following the accident, and the moments leading up to it. The two father-daughter themes Stephens & Zoe, Nicole & Sam) are subtlely yet intensely interwoven. The dialogue is also the most natural of any of Egoyan’s films, markedly different from the minimalist, consciously weighted lines of some of his other work. I’ve become accustomed to the latter, but I appreciate when Egoyan’s aesthetic discipline occasionally relaxes a little. Hereafter is more Bergman than Beckett.

Sarah Polley, of course, has fulfilled every bit of the promise she showed from her earliest appearances as an actress. She followed in Egoyan’s footsteps by both writing and directing Away from Her (2006), a masterful adaptation of Alice Munro’s short story “The Bear Came over the Mountain.” In 2017, she produced and wrote the scripts for the television mini-series based on Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace. Artists such as Polley, Egoyan, Don McKellar, Paul Gross, and Winnipeg’s Guy Maddin have devoted their talents for the last 30 years to ensure that English-Canadian cinema makes its mark in the world.