“Once one becomes interested in the game, there is no knowing where one will stop.”

–from Les Liaisons Dangereuses

I’d originally planned this month’s column along the lines of those A & E Biography theme weeks, where each day of the week might feature a different documentary about notorious gangsters or celebrated altruists. My cheery theme was going to be “American psychos,” featuring three of contemporary cinema’s most sinister characters. I’ve kept the theme but, unfortunately, I’ve had to scratch one sociopath off my list. I feel kind of bad about that, because he was in the only movie of the three that was directed by a Canadian. The problem was that the protagonist of Mary Harron’s adaptation of Brett Easton Ellis’s controversial novel American Psycho just wasn’t scary enough. Harron’s film does have its moments of social satire and very black humor. It’s a wicked commentary on a society that sacrifices community to personal vanity. Choosing the right watermark for a business card is given the same emotional weight as choosing an axe or a nail gun for a murder weapon. But the killer in American Psycho (played by Christian Slater) seems shallow and stupid. More symbolic than visceral. He’s always on the verge of implosion, an object of pity rather than of terror. He’s also out of his league in a match-up with the Colombo-like private eye played by Willem Dafoe. Nice try, but no bogeyman

So rather than an unholy triumvirate, I’m left with a twisted dyad. Kalifornia is an ice storm of cold violence. The Talented Mr. Ripley is a long spiral into hell. The protagonist of the former is utterly repellent, killing with little motive and zero remorse. The Talented Mr. Ripley features the boy next door carrying a weight of guilt that would do Dostoevsky proud. For both, murder is a survival mechanism.

Let’s start with the tragic. Class warfare. The very rich can often lead lives hugely destructive of the not-so-rich whose paths cross their own. Wealth is often the eye of the hurricane; the wealthy remain untouched in the center while the less fortunate are drawn into the whirlwind and destroyed or cast off broken and bewildered. This scenario usually plays out in a European setting–with its monarchies, its aristocracies, its jet sets, and its backdrops of villas and canals and casinos. Two splendid examples of the genre are Choderlos de Laclos’ Dangerous Liaisons and Henry James’ The Wings of the Dove (both with excellent screen adaptations by Milos Forman and Iain Softley, respectively).

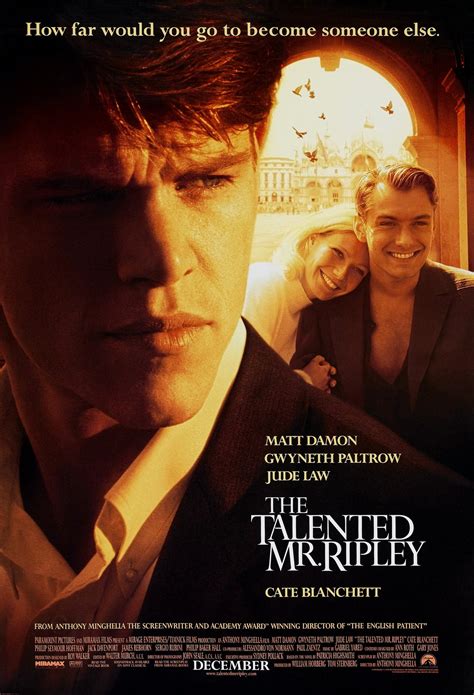

For a while, it seems that the hurricane metaphor will suit The Talented Mr. Ripley nicely. Matt Damon plays the role of Tom Ripley, an ambitious young nobody who, thanks to a borrowed Princeton jacket, is mistaken for a young man much above his actual station in life. He calls life’s bluff and winds up getting himself sent on an all-expenses-paid trip to Italy to track down and bring home the decadent son of an American millionaire.

Despising his father, the wayward son, Dickie Greenleaf (Jude Law), conspires with Tom to supplement his lifestyle by ripping off even more of the old man’s money than he’s accustomed to doing. Dickie initiates Tom into the high life of sun, sea, and jazz. The game is fun for a while. Tom gets used to living beyond his means. Dickie gets to play a bit of Professor Higgins to Tom’s Eliza Doolittle. Then things begin to fall apart. Dickie’s a wastrel but no fool; he has pegged Tom for the imposter he is. As soon as Tom’s novelty wears off, Dickie’s looking for a new toy. He’s a serial dilettante, using and discarding people and fashions. Tom, who thinks he’s been making new friends, and is sexually attracted to both Dickie and his fiancée (played by Gwyneth Paltrow), finds himself shut down and shut out.

Bad move. Tom’s not about to be whirled into oblivion. Time to switch metaphors. Instead of a sybaritic hurricane, think of Dickie Greenleaf’s playboy lifestyle as a well-oiled pleasure machine. The gears turn smoothly; they are made of steel and grind up anything soft that’s pulled inside, like hearts and flesh. Tom Ripley should be more grist for the mill. Instead, there’s a core of desperation in Tom that proves indigestible. He starts ripping the machine apart from the inside, clawing his bloody way out. What began with a lie about a borrowed jacket becomes a waking nightmare with an accelerating body count. Tom’s tragedy is that he’s fully aware that he’s becoming a monster, without being able to comprehend how or take any action to stop the transformation. The first murder could have been blind rage. What about the second? The third? Where will it end when you’ve killed what you love as well as what you hate? Tom Ripley has the worst of two worlds: he has a sociopath’s instincts for survival, and a sane man’s capacity for guilt….

The Talented Mr. Ripley is like watching a minor Greek tragedy. Kalifornia is a contemporary Titus Andronicus. Popcorn anyone? [Author’s Note: the portion of this column dedicated to Kalifornia is entered as a separate entry for the website.]

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

Because I knew where things were headed this time around, I don’t think I reacted quite as strongly to the film on this second viewing. I still found it disquieting, however, like watching an episode of Midsomer Murders or Endeavour where the killer, against all expectations, walks away free at the end with no one the wiser. Director Anthony Minghella and cinematographer John Seale do an excellent job of playing off the National Geographic settings against Tom Ripley’s homicidal social climbing and Dickie Greenleaf’s vicious narcissism. The homoerotic elements to the story stood out more sharply for me this time, giving an added dimension to Ripley’s disgust at his own lack of status. At the same time that he’s trying to create a new identity by stealing Dickie’s, Ripley is struggling with his sexual identity. Matt Damon is in good company in taking on a role that’s attracted several high-profile directors and actors: Alain Delon in Plein Soleil (1960), directed by René Clément; Dennis Hopper in Wim Wenders’ The American Friend (1977), and John Malkovich in Liliana Cavani’s Ripley’s Game.

Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow, Cate Blanchett, and Philip Seymour Hoffman deliver strong, nuanced performances that manage to feed Ripley’s lust, envy, paranoia, anger, and hunger.

Nowadays, of course, Ripleyesque anti-heroes are everywhere. The rogues’ gallery would include The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Dexter, Deadwood, American Psycho, and The Silence of the Lambs. But when Patricia Highsmith first published The Talented Mr. Ripley in 1955, her novel would have caught many readers completely unprepared. I’d love to read some of the contemporary reviews. The so-called “Ripliad” would eventually consist of five novels, the last appearing in 1991. As I’m often forced to do in these updates, I confess that I have yet to read any of Highsmith’s work. Shame on me. The Talented Mr. Ripley is on my desk as I write this. I’m curious about the many Imdb User Reviews that found the film markedly inferior to the book. I might expect the novel to be different, but on the strength of its performances I’d guess that the movie holds its own for me.

Tragically, director Anthony Minghella died in 2008 of a hemorrhage, age 54. Philip Seymour Hoffman died in 2014, age 46, of complications from drugs and alchohol.

Matt Damon, Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow, and Cate Blanchett show no signs of putting the brakes on their high-profile acting careers. Damon and Paltrow have one Oscar apiece; Blanchett has two Oscars, Law is a two-time nominee for an Academy Award. Between them, they have well over 300 acting credits on Imdb.

Available on YouTube? No, but available for rental or purchase through YouTube & iTunes