https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=udVcEcGYw-Q

Also worth checking out is Lang’s Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler (1922). There’s a high quality copy on YouTube, but with German intertitle cards:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UuJRs9xvkPg (Part 1)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6UBj6Z_CJJI (Part 2)

An abridged version of Part 1, with English intertitles, is available here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MulihI2Mx80

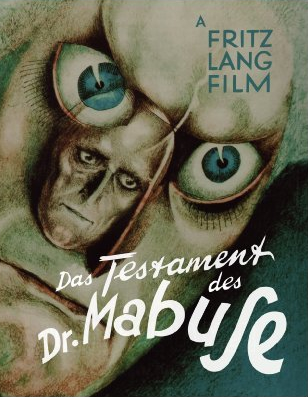

Quick! Name the great detective/villain combos. Sherlock Holmes & the nefarious Moriarty. Nayland Smith & the insidious Dr. Fu Manchu. Inspector Lohmann & the diabolical Dr. Mabuse……Whoa! Wait a second. Inspector Lohmann? Dr. Mabuse? These guys are famous? Well, sort of. Long before their more illustrious counterparts were brought to the screen, the great German director Fritz Lang determined the Shape of Things to Come with a series of films featuring a Master of Crime and a Master of Criminals. Both Dr. Mabuse and Inspector Lohmann would become role-models for countless evil geniuses and hard- nosed lawmen to come, and the films in which they starred continue to hold up well in this age of high-tech, Indiana Jones-style razzle-dazzle. I’ve never seen the first of the Mabuse films, Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1924), a reputedly sometimes brilliant 200-minute-plus opus, but I had a wonderful time with the sequel—The Testament of Dr. Mabuse.

Made in 1933, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse seems astonishingly precocious. Special effects? How about underwater explosions, towering infernos, hallucinations, and spectres? Car chases? How about a high-speed chase down country roads at night? Plot? How about murder by hypnotic suggestion, criminal empires, an attempt to Destroy Civilization As We Know It, drive-by assassination, ticking time bombs, the occasional madman, and a love story? Not to mention some wonderful overacting, some memorably twisted German expressionist decor….and Lohmann and Mabuse.

As played by Otto Wernicke, Lohmann is the prototype for every “tough cop” to come—cigar smoking, disheveled, disgruntled, arrogant, relentless. He’s so bad he doesn’t even need to use a gun; criminals surrender as soon as they find out he’s outside the door waiting for them. More impressive still, he’s part of the Holmesian tradition which sees police work as more science than machismo. Although he looks like he could manhandle an apartment building, Lohmann browbeats his suspects with forensic evidence rather than his fists. The Testament of Dr. Mabuse marks Lohmann’s second appearance in a Lang film; his first was in M (1931), Fritz Lang’s powerful story of the hunt for a child-killer (played by Peter Lorre in his most memorable role).

Mabuse is played by another of Lang’s favourite actors, Rudolf Klein Rogge. It was Rogge who also incarnated the deranged magician/inventor, Rotwang, in Lang’s 1927 science fiction masterpiece, Metropolis. The director later commented that he’d modeled Mabuse and his criminal cabal on Hitler and the Nazi Party (who returned the favour by banning the film), but I’d rather take Mabuse on his own fiendish terms. Let’s savour our villains a little, before we overlay them with the weight of history. After all, like great heroes, heroines & lovers, great villains give themselves, and us, a chance to indulge in superlatives. It was the abominable Dr. Otto von Niemann who said it best: “‘Mad? I, who have solved the Secret of Life, you call me mad!!?” Mabuse, confined to an asylum, scrawls a demonic testament which reveals to his ill-fated psychiatrist that he has “the soul of Man tormented by the Madness of Crime. Crime whose only object is to spread Horror!” and concludes with the ringing declaration “that when mankind is ruled by terror, then is the hour for the Mastery of Crime! “

Neither insanity nor death seem sufficient to crimp Mabuse’s style, and his insatiable hunger for power for its own sake reaches beyond the grave. His own victims deliver the best eulogies:

‘The criminal übermensch! No one knows what a superhuman brain he had! His brain was rotten…with egoism, madness, and haired! A brain which sought only to destroy!”

Thank goodness for melodrama! When else do you get to use that many exclamation marks in a row? If we owe the anti-fascist sentiment of The Testament of Dr. Mabuse to Fritz Lang, we can credit the potent melodrama to his screenwriter and wife, Thea von Harbou. Because of her later affiliation with the Nazi party, von Harbou has perhaps never been given full credit for her contributions to cinema history. She was responsible for the screenplays of several of the great German films of the 20s and 30s, all of which are currently in circulation and have been either remade or endlessly “quoted” in pop culture. Her credits include Destiny, Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, Siegfried, Kriemhild’s Revenge, Metropolis (based on her own amazing novel of the same title), M, and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. The list makes quite a testament in its own right. Her collaborations with her husband, and their marriage, ended when Lang fled Germany in 1933 and von Harbou remained behind to work for the New German Order. History judges harshly. Thea von Harbou is mentioned in the biographies of the directors whose work she helped make great. She deserves a biography of her own.

Another key member of Fritz Lang’s production team was the photographer Fritz Amo Wagner. Wagner and Carl Freund were the two great cinematographers of Germany’s cinematic Golden Age. Perhaps there can be no greater tribute to these two men’s skill than the fact that on a recent trip to Spokane I came across no fewer than four different editions of Metropolis (photographed by Freund), and three of Nosferatu (photographed by Wagner), on sale in local video stores. Freund and Wagner pioneered the German expressionist “look” noted for its eerie sets, grotesque physiognomies and uncanny lighting. All are in evidence in Mabuse.

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, and most of the other classic expressionist films mentioned in this review, are available at Reo’s Videos. Try a double feature. And as you settle down by the fireplace, whisper along with Edward Young:

“I hate the Spring, I turn away

From gaudy Scenes of flow’ry May

The Death of Nature, the severe

And wintry Waste, to me more dear.

Yes, welcome Darkness! Welcome Night!

Thrice welcome every dread Delight!

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

“The ultimate purpose of crime is to establish the endless empire of crime. A state of complete insecurity and anarchy, founded upon the tainted ideals of a world doomed to annihilation. When humanity, subjugated by the terror of crime, has been driven insane by fear and horror, and when chaos has become supreme law, then the time will have come for the empire of crime.” –Dr. Mabuse

Prior to 9/11 and the new War on Terror that has replaced the Cold War, the chief claims to fame of The Testament of Dr. Mabuse would have been its early demonstration of the effectiveness of sound, its seminal role in the evolution of film noir and the James Bondian supervillain, its brilliant editing, and its prefiguration of the Nazi reign of terror. Unfortunately, in our contemporary age of Al-Qaeda, ISIS/Daesh, and rising xenophobia, the most disturbing element of The Testament now becomes its prescience in creating a villain whose goal is to remake the world in his own image through the chaos unleased by violent attacks on infrastructure, chemical warfare, subversion of the global monetary system, poisoning of water supplies, and a wholesale escalation of paranoia. Welcome to the 21st century.

The film’s resonance with our beleaguered world aside, however, Testament remains a notable but flawed film. It’s not quite at the level of Fritz Lang’s work on M or Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler. And that’s not damning by faint praise. The latter two films set a very high bar. M is more successful as a self-contained cinematic masterpiece; The Gambler is more potent in capturing the spirit of a decadent, disintegrating society. But there remains much to admire in Testament, and I’ll focus on the film’s strengths in the discussion that follows.

The opening scene of Testament is a tour de force in the use of diegetic sound (“Sound whose source is visible on the screen or whose source is implied to be present by the action of the film….Diegetic sound is any sound presented as originated from source within the film’s world. Diegetic sound can be either on screen or off screen depending on whatever its source is within the frame or outside the frame”—definition from FilmSound.org). We see a man cowering like a rat in a bizarrely, claustrophobically-clustered basement, but what we hear is the incessant pounding of some great machine that we never see. With hindsight, it’s like a thousand jackboots prophesying the coming Reich. I don’t know if I’ve ever heard anything more terrifying in its nameless menace.

Here, as in almost all his films, Lang’s use of high contrast lighting (“spellbind chiaroscuro”)—including the classically-noirish venetian blind effect—influenced countless other filmmakers. There’s nothing quite like Testament’s nighttime car chase scene, as much a race into madness as it is a nerve-shredding physical journey. In Testament, the lighting is matched perfectly to claustrophobic spaces created by Art Designers Emil Hassler and Karl Vollbrecht. Rooms seem too small, either overstuffed with bric-a-brac or antiseptically bare of ornament. Into this mix is added Lang’s superb use of superimposition to ratchet up psychological terror.

Dr. Mabuse is one of cinema’s great villains, a worthy successor to Conan Doyle’s Professor Moriarty. Even death can’t stop him. He walks that knife-edge between genius and madness. Trust the German language to have a word for it: Allmachtsphantasien (“fantasies about omnipotence”). Mabuse is also, in essence, a kind of vampire. Inspector Karl Lohmann is his perfect foil, almost as scary in his cigar-chomping, bull-in-a-china-shop, thank-God-he’s-on-our-side kind of way.

Fritz Lang was obsessed with detail. You can see that obsession in the attention paid to even the relatively bare Wizard-of-Oz-like room where Tom and Lilli are trapped with a ticking time bomb. The physicality of the room traps us as much as it traps them. If shots are fired, you can be sure there will be bullet holes to match.

In 1943, for the New York debut of Testament, Lang himself commented on his intentions. Here are his remarks, as quoted by Sigfried Kracauer:

“This film was made as an allegory to show Hitler’s processes of terrorism. Slogans and doctrines of the Third Reich have been put into the mouths of criminals in the film. Thus I hoped to expose the masked Nazi theory of the necessity to deliberately destroy everything which is precious to a people….Then, when everything collapsed and they were thrown into utter despair, they would try to find help in the ‘new order.’”

Joseph Goebbels, Reich Minister of Propaganda, must have smelled a rat because he immediately banned The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (the film might have been lost forever, if Lang had not managed to smuggle out a French version of the film that had been shot at the same time). Interestingly, however, Goebbels also offered Lang a job as the head of the Reich’s film production unit. The confusion is understandable: there’s a flirtation with fascism in Lang’s German films that came from the fact that many of his screenplays were written by his wife, Thea von Harbou—who joined the Nazi party in 1931 and chose to stay in Germany when Lang caught the first train out of the country.

I’ll leave the last word to David Thomson, from his one-page review of Testament in “Have You Seen…?” A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films: “…it is a fair fight [between Mabuse and Lohmann] and a quite terrific suspense picture, enough to feed Hitchcock for years and keep OO7 busy in decades to come. This is a seminal film in noir, paranoia, and the criminal web motifs.”

Part 2:

Some thoughts on Lang’s sequel, Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler

Two words. Chairs. Doors.

Seen on a big screen, Dr. Mabuse is, visually, one of the high points of the silent cinema. It’s a four-hour feast of over-the-top set design by Otto Hunte, Karl Stahl-Urach, Erich Kettelhut, and Karl Vollbrecht. There’s hardly a door here that’s under ten feet high, the ceilings are stratospheric, Count Told’s sitting room is a cross between a museum of anthropology and Grand Central Station, the wallpaper’s out of Caligari, interiors of buildings have no relation to exteriors, perspective is forced by set construction, no two chairs are alike (with most finding a happy home in Paris’s Musée des art décoratifs), telephones & clocks are alien life forms, and the artwork on the walls is what you might expect if the creepiest carnival in the world rolled into town at midnight. Check out that painting of Lucifer above the fireplace—it’s straight out of William Blake, or maybe Aleister Crowley’s Tarot. Expressionism meets art nouveau meets art deco meets Kunstgewerbe meets what-in-the-hell-was-that?

The protean theme continues with Mabuse as the master of disguise. He’s a slick psychoanalyst, a Jewish street peddler, a drunken dock worker, a Russian aristocrat, a plutocrat, a Rasputin clone, and a who-in-the-hell-is that? By contrast, the “hero” is about as dynamic as drying paint. Our uber-villain has no peer. Sigfried Kracauer sums things up perfectly: “As so often with Lang, the law triumphs and the lawless glitter.” Even the henchmen are memorable: a twitchy effete cocaine fiend, a Twiddledum thug, a doomed femme fatale, and stone-cold assassin.

Lang subtitled the two halves of Dr. Mabuse “Image of our Times” and “Inferno—Men of our Times.” He really was trying to capture the disturbed heart of post-War Germany and the Weimer Republic. As someone said of Dr. Mabuse, “It is by no means a documentary film, but it is a document of its time.” Lotte Eisner makes reference to the “hieroglyphics of an ineffable solitude and despair.” Poverty versus plutocracy, the fat cats & rapacious industrialists versus the plebs. Dr. Mabuse is as close as the cinema comes to the Expressionist paintings of George Grosz and Otto Dix. Chaos breeds tyrants, who capitalize (pun intended) on chaos. Dr. Mabuse himself doesn’t want money, he wants victims. He wants to play with life and death.

Need evidence of brilliant editing and composition? How else do you keep an audience’s attention for four hours? A young Sergei Eisenstein was blown away when he saw the film. From Kracauer: “The relation between Dr. Mabuse and this chaotic world is revealed by a shot to which Rudolf Arnheim has drawn attention. A small bright spot, Mabuse’s face gleams out of the jet-black screen, then, with frightening speed, rishes to the foreground and fills the whole frame, his cruel, strong-willed eyes fastened upon the audience. This shot characterizes Mabuse as a creature of darkness, devouring the world he overpowers.”

A final, somewhat sad note: The creator of Dr. Mabuse, Luxembourgeois novelist Norbert Jacques, was forced to sell the rights to his character for a pittance. He received no royalties from the films based on his creation.

Cue Ernst Stavro Blofeld…..