–“Are you happy?”

–“I’m not unhappy.”

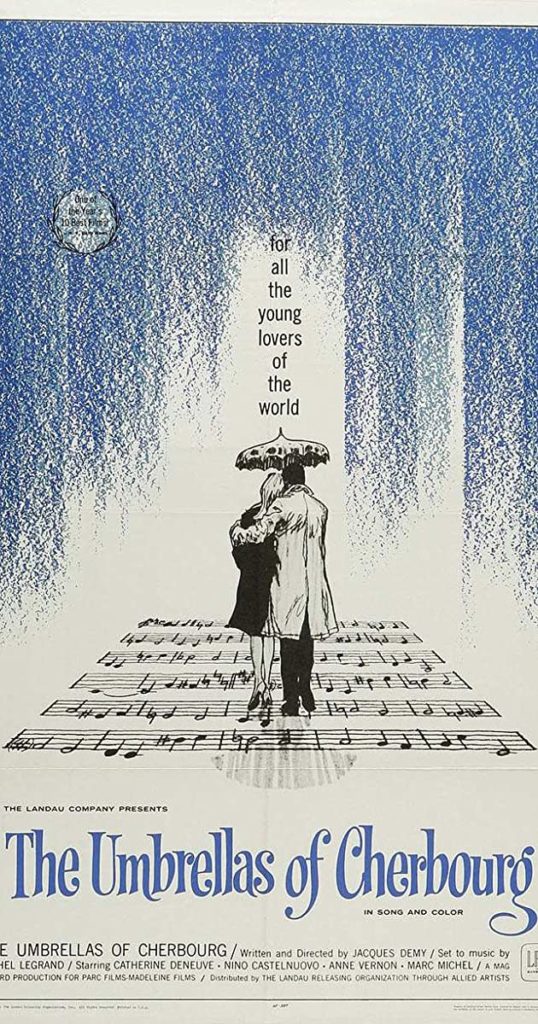

If you haven’t seen Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, and this review piques your interest, I’ve got a little favour to ask of you: Hold off on making any critical judgements until you’ve been watching for at least fifteen minutes or so. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is a musical, but it definitely isn’t Singing in the Rain or Moulin Rouge. Actually, I don’t think there’s another musical like it in existence: no dancing, no duets, no chorus, and no spoken lines of dialogue. Lines like, “Check the ignition on the Mercedes,” “I should have changed shoes,” and “Move your ass, you’re in the way” are all delivered with the same musical conviction as Judy Garland singing about the Yellowbrick Road.

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg was an experiment. The fact that it didn’t create a whole new genre of movie musicals doesn’t mean it wasn’t a brilliant success on its own terms. But it sure takes a bit of getting used to. That’s why I was asking for that little favour. There might be a temptation to watch for five minutes and scream, “Jacques, are you mad!? There’s a reason no one ever did this before!” Hey, that was my first reaction. Rubbing it in, Demy has one of his characters sing: “All that singing gives me a pain—I like the movies better.”

In France, Demy’s film is one of the great classics. Yea, I know, they worship Jerry Lewis too. This time it’s more than just a national quirk. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg was nominated for 5 Academy Awards in 1964, and won the Palme d’Or for best film at Cannes. Once you accept the every-line’s-a-lyric premise, the critical recognition doesn’t seem misplaced. With its extraordinary use of colour and the superb musical score by Michel Legrand, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg develops a bittersweet love story in the best tradition of Jacques Brel and Jacques Prévert.

Those of us who weren’t around to see the original film almost missed out on the chance to appreciate it. Demy used an Eastmancolor process that’s turned out to be very unstable. Eastmancolor films tend to suffer from a loss of strength in blues and greens over time, leaving the films looking pink and washed out. By the 1980s, no true print of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg was known to exist. Presciently, Jacques Demy had archived multiple monochromatic negatives when he produced the original film. Shortly before his death in 1990 he began work on creating a new print. His widow, Agnès Varda, herself one of France’s finest filmmakers, completed the restoration in 1992. Michel Legrand also remixed the soundtrack in Dolby stereo. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

Even if The Umbrellas of Cherbourg weren’t such a bold experiment, it would still have a 20-year-old Catherine Deneuve in her first starring role. Deneuve’s debut could have been Demon Hot-Rods of Lyon and it still would have made my must-see list. In Cherbourg she is Geneviève, a teenager whose widowed mother owns an umbrella store that gives the film its name. Business is not good. Behind her mother’s back, Geneviève has started going out with Guy (Nino Castelnuovo), a 20-year-old mechanic at a local garage who lives with his invalid godmother and her caretaker. The courtship is accelerated when Guy gets his draft papers for Algeria (the film’s story begins in November, 1957). Mom clues in to what’s going on and is not happy—she has no illusions about love.

The plot thickens with the arrival of a wealthy young bachelor, Roland (Marc Michel). From the moment Roland arrives on the scene, Demy’s film veers radically away from the simple-minded paean to love less-gifted hands might have made of it. Like the songs and poems of Brel and Prévert, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg manages to be sublimely romantic while keeping its eyes wide open. Demy’s choice to have every line of dialogue sung creates an ironic distance that the storyline both reinforces and denies. At one moment, lines of poetry flow together in rhyme à la Cyrano de Bergerac; at the next it’s back to an operatic, “Will that be regular gas or premium?” Lines such as “I can’t live without you!” and “I will love you till the end of my life” work because they’re come across as both heartfelt and unreal.

The film’s editing contributes to the surreality. A couple of strange, abrupt cuts catch the viewer off guard, reminders of illusion. Amazing shots like the opening one of the film, looking straight down at the street as the rain falls away from the camera and the umbrellas bloom like sudden flowers (or the one where Guy and Geneviève literally float down a sidewalk, and the one later at the train station where the camera pulls away with the train instead of following it), are spellbinding at the same time they remind us that we’re in a kind of fairy tale encroached upon by the world outside. Imagine Gene Kelly or Fred Astaire as Vietnam vets.

Michel Legrand’s music reinforces the viewer’s subtle disorientations. Lush, jazzy, swelling, falling. Manipulative. Gorgeous.

Color is a stunning part of this almost fairy tale. It takes the place of “Once upon a time….” The inhabitants of Demy’s Cherbourg exist in world of primary colours and backgrounds that are half Las Vegas, half Martha Stewart. Sometimes the colours wrap around the characters like warm luminous blankets, while at others times the actors seem like flesh and blood silhouettes on a Technicolor scrim. Cinematic Post-Impressionism. Fruits in a bowl command one’s attention as strongly as faces. Demy and his set designer actually repainted whole sections of Cherbourg to match the vision they had for the film. There is a fantastic attention to detail. When Guy and Genevieve sit together on their last evening before Guy leaves for the army, the drinks on their table are colour-coordinated with everything else in the scene. The attention to detail extends to subtleties of plotting, things easily missed on a first viewing.

This film begins in rain and ends in snow. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is not a fairy tale about living happily ever after. It is a fairy tale about not living unhappily ever after. And that, it turns out, is not a fairy tale at all.

(I’d also like to recommend Jonathan Rosenbaum’s excellent essay on Jacques Demy’s films, “Songs in the Key of Everyday Life,” on the web at https://chicagoreader.com/film/songs-in-the-key-of-everyday-life/)

Looking Back & Second Thoughts

For me, the magic of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg comes from the way in which Jacques Demy managed to give an epic/archetypal feel to a simple love story between a garage mechanic and a salesgirl in a small coastal city. He did this through a combination of the preternatural beauty of the young Catherine Deneuve, the paradoxical way the sung dialogue draws us deeper into characters’ lives rather than alienating us from them, the pastel color fantasy of sets and costumes, occasional moments of magic realism (such as the scene where Guy, accompanied by Geneviève, walks his bike down a street and yet appears to float on air rather than walk), and the final, bittersweet recognition that human beings, while able find accommodations with life that serve to make them not unhappy, find true happiness just out of reach. Simple as this love story may appear to be, it’s as superb as Cyrano de Bergerac’s sacrifice of his own love on the altar of Roxane and Christiane’s more earthly passion. Neither Geneviève nor Guy could have found more honest loves than Roland’s and Madeleine’s—and they know this to be true—but they are doomed to forever wonder if what they’ve given up is something beyond reckoning or price.

Random Notes:

- None of the actors in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg actually sing for the finished film. All the singing was recorded separately by others, and a painstaking effort was required of the actors to synch their lip movements to the recorded tracks. When performing before the camera, however, the actors did actually sing—very badly, it appears—to create the most convincing effect possible.

- Following in the French New Wave tradition, Demy shot all of his films on location, never in a studio. With The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, however, that didn’t stop him from altering the look of locations through painting, new wallpaper, etc.

- Composer Michel Legrand, who died in 2019, had an extraordinarily successful career that embraced jazz, classical, popular music, and early French rock ‘ n roll. He had three Oscar wins, and another half dozen nominations. The Internet Movie Data Base lists 215 credits as a composer for film & television. He recorded over 100 albums.

- Catherine Deneuve’s career has been as remarkable as Legrand’s. She has 141 acting credits on Imdb as of January 2002 and is still making one or two films a year. She’s taken home two César Awards in France, with an additional dozen nominations.

- Jacques Demy died in 1990, at age 59, from HIV/AIDS. His last film was Three Seats for the 26th, made in 1988. Demy’s partner, filmmaker Agnès Varda, has released three documentary films on Demy’s life & art: Jacquot de Nantes (1991), Les demoiselles ont eu 25 ans (1993), and L’Univers de Jacques Demy (1995).

- If you have access to the Criterion DVD for the film, or to the Criterion Channel, to bonus features are first-rate: a one-hour French documentary on Cherbourg from 2008, an interview with film scholar Rodney Hill that puts Cherbourg & Demy in the context of the French New Wave and more traditional French cinema, a 1964 television interview with Jacques Demy & Michel Legrand, and audio interviews with Demy & Deneuve recorded in London in 1991.

Available on YouTube? No, but currently available at Bing.com at

Also available for purchase or rental through iTunes & YouTube, and for streaming at the Criterion Channel